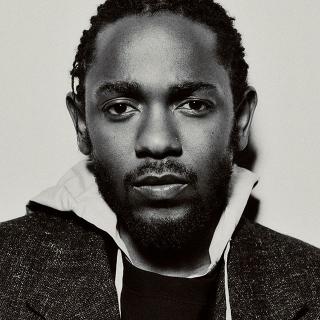

KENDRICK LAMAR

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth was born in Compton, California, USA on June 17, 1987. Lamar’s parents moved there from Chicago in 1984, three years before Kendrick was born. His dad, Kenny Duckworth, was reportedly running with a South Side street gang called the Gangster Disciples, so his mom, Paula Oliver, issued an ultimatum. “She said, ‘I can’t *** with you if you ain’t trying to better yourself,’ ” Lamar recounts. “‘We can’t be in the streets forever.’ ” They stuffed their clothes into two black garbage bags and boarded a train to California with $500. “They were going to go to San Bernardino,” Lamar says. “But my Auntie Tina was in Compton. She got ’em a hotel until they got on their feet, and my mom got a job at McDonald’s.” For the first couple of years, they slept in their car or motels, or in the park when it was hot enough. “Eventually, they saved enough money to get their first apartment, and that’s when they had me.”

Lamar has a lot of good memories of Compton as a kid: riding bikes, doing back flips off friends’ roofs, sneaking into the living room during his parents’ house parties. (“I’d catch him in the middle of the dance floor with his shirt off,” his mom says. “Like, ‘What the . . . ? Get back in that room!’ ”) Then there’s one of his earliest memories — the afternoon of April 29th, 1992, the first day of the South Central riots.

Kendrick was four. “I remember riding with my pops down Bullis Road, and looking out the window and seeing motherfuckers just running,” he says. “I can see smoke. We stop, and my pops goes into the Auto-Zone and comes out rolling four tires. I know he didn’t buy them. I’m like, ‘What’s going on?’ ” (Says Kenny, “We were all taking stuff. That’s the way it was in the riots!”)

“Then we get to the house,” Lamar continues, “and him and my uncles are like, ‘We fixing to get this, we fixing to get that. We fixing to get all this shit!’ I’m thinking they’re robbing. There’s some real mayhem going on in L.A. Then, as time progresses, I’m watching the news, hearing about Rodney King and all this. I said to my mom, ‘So the police beat up a black man, and now everybody’s mad? OK. I get it now.’ ”

“He was always a loner,” Kendrick’s mom says. Lamar agrees: “I was always in the corner of the room watching.” He has two little brothers and one younger sister, but until he was seven, he was an only child. He was so precocious his parents nicknamed him Man-Man. “I grew up fast as ****,” he says. “My moms used to walk me home from school — we didn’t have no car — and we’d talk from the county building to the welfare office.” “He would ask me questions about Section 8 and the Housing Authority, so I’d explain it to him,” his mom says. “I was keeping it real.”

The Duckworths survived on welfare and food stamps, and Paula did hair for $20 a head. His dad had a job at KFC, but at a certain point, says Lamar, “I realized his work schedule wasn’t really adding up.” It wasn’t until later that he suspected Kenny was probably making money off the streets. “They wanted to keep me innocent,” Lamar says now. “I love them for that.” To this day, he and his dad have never discussed it. “I don’t know what type of demons he has,” Lamar says, “but I don’t wanna bring them s***s up.” (Says Kenny, “I don’t want to talk about that bad time. But I did what I had to do.”)

Lamar recalls sitting on his dad’s shoulders outside the Compton Swap Meet, age eight, watching Dr. Dre and 2Pac shoot a video for “California Love.” “I want to say they were in a white Bentley,” Lamar says. (It was actually black.) “These motorcycle cops trying to conduct traffic but one almost scraped the car, and Pac stood up on the passenger seat, like, ‘Yo, what the ****!’ ” He laughs. “Yelling at the police, just like on his m*******g songs. He gave us what we wanted.” He quit drinking and smoking weed when he was around 16 or 17 and focused on his rap career, something he’d been interested in since watching Dr. Dre and Tupac Shakur film the music video.

Being a rapper was far from preordained for Lamar. As late as middle school, he had a noticeable stutter. “Just certain words,” he says. “It came when I was excited or in trouble.” He loved basketball — he was short, but quick — and dreamed of making it to the NBA. But in seventh grade, an English teacher named Mr. Inge turned him on to poetry — rhymes, metaphors, double-entendres — and Lamar fell in love. “You could put all your feelings down on a sheet of paper, and they’d make sense to you,” he says. “I liked that.”

At home, Lamar started writing nonstop. “We used to wonder what he was doing with all that paper,” his dad says. “I thought he was doing homework! I didn’t know he was writing lyrics.” “I had never heard him say profanity before,” says his mom. “Then I found his little rap lyrics, and it was all ‘Eff you.’ ‘D-*-*-k.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, my God! Kendrick’s a cusser!’ ”

An A student, Lamar flirted with the idea of going to college. “I could have went. I should have went.” (He still might: “It’s always in the back of my mind. It’s not too late.”) But by the time he was in high school, he was running with a bad crowd. This is the crew he raps about on good kid, m.A.A.d City — the ones doing robberies, home invasions, running from the cops.

Once his mom found a bloody hospital gown, from a trip he took to the ER with “one of his little homeys who got smoked.” Another time she found him curled up crying in the front yard. She thought he was sad because his grandmother had just died: “I didn’t know somebody had shot at him.” One night, the police knocked on their door and said he was involved in an incident in their neighborhood, and his parents, in a bout of tough love, kicked him out for two days. “And that’s a scary thing,” Lamar says, “because you might not come back.”

After a couple of hours, the mood on Rosecrans, where we are sitting starts to shift. An ambulance roars by, sirens blaring. In the middle of the street, a homeless man is shouting at passing cars. Lamar starts to grow uneasy, his eyes glancing at the corners. I ask if everything’s OK. “It’s the temperature,” he says. “It’s, uh, raising a little bit.” A few minutes later, one of his friends — who’s been cruising back and forth on his bicycle all afternoon, “patrolling the perimeter” — calls out, “Rollers!” and a few seconds later, two L.A. County sheriff cruisers round the corner. “There they go,” Lamar says, as they hit their lights and take off.

As a teenager, “the majority of my interactions with police were not good,” Lamar says. “There were a few good ones who were actually protecting the community. But then you have ones from the Valley. They never met me in their life, but since I’m a kid in basketball shorts and a white T-shirt, they wanna slam me on the hood of the car. Sixteen years old,” he says, nodding toward the street. “Right there by that bus stop. Even if he’s not a good kid, that don’t give you the right to slam a minor on the ground, or pull a pistol on him.”

Lamar says he’s had police pull guns on him on two occasions. The first was when he was 17, cruising around Compton with his friend Moose. He says a cop spotted their flashy green Camaro and pulled them over, and when Moose couldn’t find his license fast enough, the cop pulled a gun. “He literally put the beam on my boy’s head,” Lamar recalls. “I remember driving off in silence, feeling violated, and him being so angry a tear dropped from his eye.” The story of the second time is murkier: Lamar won’t say what he and his friends were up to, only that a cop drew his gun and they ran. “We was in the wrong,” he admits. “But we just kids. It’s not worth pulling your gun out over. Especially when we running away.”

Friends of his weren’t so lucky. Just after midnight on June 13th, 2007, officers from the LAPD’s Southeast Division responded to a domestic-violence call on East 120th Street, about five minutes from Lamar’s house. There they found his good friend D.T. allegedly holding a 10-inch knife. According to police, D.T. charged, and an officer opened fire, killing him. “It never really quite added up,” Lamar says. “But here’s the crazy thing. Normally when we find out somebody got killed, the first thing we say is ‘Who did it? Where we gotta go?’ It’s a gang altercation. But this time it was the police — the biggest gang in California. You’ll never win against them.”

On an otherwise positive song called “HiiiPower,” from his 2011 mixtape Section.80,Lamar rapped, “I got my finger on the m*******g pistol/Aim it at a pig, Charlotte’s Web is going to miss you.” It’s an unsettling line, especially coming from a rapper who often subverts gangster tropes but rarely trafficks in them. “I was angry,” he says. “To be someone with a good heart, and to still be harassed as a kid . . . it took a toll on me. Soon you’re just saying, ‘**** everything.’ That line was me getting those frustrations out. And I’m glad I could get them out with a pen and a paper.”

About three years ago, Lamar was flipping through the channels on his tour bus when he saw on the news a report that a 16-year-old named Trayvon Martin had been shot to death in a Florida subdivision. “It just put a whole new anger inside me,” Lamar says. “It made me remember how I felt. Being harassed, my partners being killed.” He grabbed a pen and started writing, and within an hour, he had rough verses for a new song, “The Blacker the Berry”.

But as Lamar wrote, he also started thinking about his own time in the streets, and “all the wrong I’ve done.” So he started writing a new verse, in which he turned the microscope on himself. How can he criticize America for killing young black men, he asks, when young black men are often just as good at it? As the song’s narrator put it, “Why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street/When gangbanging make me kill a nigga blacker than me?/Hypocrite.”

When it was finally released, the song sparked a rash of think pieces, with some listeners saying Lamar was ignoring the real problem: the systemic racism that created the conditions for black-on-black crime in the first place. Coupled with a recent Billboard interview in which Lamar seemed to suggest that some of the responsibility for preventing killings like that of Michael Brown lay with black people themselves, some fans thought he sounded like a right-wing apologist. The rapper Azealia Banks called his comments “the dumbest s**t I’ve ever heard a black man say.”

Lamar says he’s not an idiot. “I know the history,” he says. “I’m not talking about that. I’m talking from a personal standpoint. I’m talking about gangbanging.”

He grew up surrounded by gangs. Some of his close friends were West Side Pirus, a local Blood affiliate, and his mom says her brothers were Compton Crips. One of his uncles did a 15-year stretch for robbery, and another is locked up now for the same; his Uncle Tony, meanwhile, was shot in the head at a burger stand when Kendrick was a boy. But Lamar says he was taught that change starts from within. “My moms always told me: ‘How long you gonna play the victim?’ ” he says. “I can say I’m mad and I hate everything, but nothing really changes until I change myself. So no matter how much bullshit we’ve been through as a community, I’m strong enough to say **** that, and acknowledge myself and my own struggles.”

When Lamar released the album’s first single, “i,” many fans weren’t sure what to make of it. A blast of pop positivity that samples an Isley Brothers hit recently heard soundtracking a Swiffer commercial, it felt like an odd move for Lamar, who’s known for more complex fare. People called it corny, mocked its feel-good, “Happy”-style chorus (“I love myself!”). “I know people might think that means I’m conceited or something,” Lamar says. “No. It means I’m depressed.”

Lamar is sitting in the Santa Monica recording studio where he made much of his album, dressed in a charcoal sweatsuit and Reeboks. His baseball cap is pulled low over his sprouting braids, and he speaks softly and thoughtfully, with long pauses between sentences.

“I’ve woken up in the morning and felt like s**t,” he says. “Feeling guilty. Feeling angry. Feeling regretful. As a kid from Compton, you can get all the success in the world and still question your worth.”

Lamar says he intended “i” as a “Keep Ya Head Up”-style message for his friends in the penitentiary. But he also wrote it for himself, to ward off dark thoughts. “My partner Jason Estrada told me, ‘If you don’t attack it, it will attack you,’ ” Lamar says. “If you sit around moping, feeling sad and stagnant, it’s gonna eat you alive. I had to make that record. It’s a reminder. It makes me feel good.”

Lamar also points out that the fans who scratched their heads at “i” had yet to hear “u” — its counterpoint on the album. “ ’i’ is the answer to ‘u,’ ” he says. The latter is four and a half minutes of devastating honesty, with Lamar almost sobbing over a discordant beat, berating himself about his lack of confidence and calling himself “a ******* failure.” It’s the sound of a man staring into the mirror and hating what he sees, punctuated by a self-aware hook: “Loving you is complicated.”

“That was one of the hardest songs I had to write,” he says. “There’s some very dark moments in there. All my insecurities and selfishness and letdowns. That shit is depressing as a m*****f****r.

“But it helps, though,” he says. “It helps.”

Lamar has documented his inner struggles before, most notably on “Swimming Pools,” from good kid, which explores his past troubles with alcohol and his family’s history of addiction. But once he got successful, he says, things got more difficult, not less. One of his biggest issues was self-esteem — accepting that he deserved to be where he was. And some of that came from his discomfort around white people.

“I’m going to be 100 percent real with you,” Lamar says. “In all my days of schooling, from preschool all the way up to 12th grade, there was not one white person in my class. Literally zero.

” Before he started touring, he had barely left Compton; when he finally did, the culture shock threw him. “Imagine only discovering that when you’re 25,” Lamar says. “You’re around people you don’t know how to communicate with. You don’t speak the same lingo. It brings confusion and insecurity. Questioning how did I get here, what am I doing? That was a cycle I had to break quick. But at the same time, you’re excited, because you’re in a different environment. The world keeps going outside the neighborhood.”

The week good kid was released, Lamar began keeping a diary. “It really came from conversations I had with Dre,” he says. “Hearing him tell stories about all these moments, and how it went by like that” — he snaps. “I didn’t want to forget how I was feeling when my album dropped, or when I went back to Compton.”

Lamar ended up filling multiple notebooks. “There’s a lot of weird shit in there,” he says. “Lot of drawings, visuals.” Whereas good kid was an exercise in millennial nostalgia, To Pimp a Butterfly is firmly in the present. It’s his take on what it means to be young and black in America today — and more specifically, what it means to be Kendrick Lamar, navigating success, expectation and his own self-doubt.

Musically, the album is adventurous, borrowing from free jazz and 1970s funk. Lamar says he listened to a lot of Miles Davis and Parliament. His producer Mark “Sounwave” Spears, who’s known Lamar since he was 16, says, “Every producer I’ve ever met was sending me stuff — but there was a one-in-a-million chance you could send us a beat that actually fit what we were doing.” Ali says Lamar works synesthetically — “He talks in colors all the time: ‘Make it sound purple.’ ‘Make it sound light green.’ ”

But of all the album’s colors, the most prominent is black. There are allusions to the entire sweep of

African-American history, from the diaspora to the cotton fields to the Harlem renaissance to Obama. “Mortal Man” (inspired in part by a 2014 trip to South Africa) name-checks leaders from Mandela to MLK all the way back to Moses. On “King Kunta,” a stomping blast of James Brown funk, he imagines himself as the titular slave from Roots, shouting the punchline “Everybody wanna cut the legs off him!/Black man taking no losses!”

Hanging over it all, of course, are the tragedies of the past three years: Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice. Says Sounwave, “To me, the album is perfect for right now. If the world was happy, maybe we’d give you a happy album. But right now, we are not happy.”

Lamar – who calls the album “fearful, honest and unapologetic” – is coy about what the title means. “Just putting the word ‘pimp’ next to ‘butterfly’ . . . ” he says, then laughs. “It’s a trip. That’s something that will be a phrase forever. It’ll be taught in college courses — I truly believe that.” I ask if he’s the pimp or the butterfly, and he just smiles. “I could be both,” he says.

Lamar lives down the coast from Calabasas, California with his longtime girlfriend, Whitney (he has called her his “best friend”), in a tri-level condo he rents in the South Bay, on the water. He still hasn’t splurged on much: So far his biggest purchase is a relatively modest house in the suburbs east of L.A., which he bought for his parents more than a year ago. Top Dawg says that at first his mom didn’t want to take it, because it meant giving up their Section 8 status. Kendrick had to reassure her: “It’s OK, Mom. We’re good.” (“It was hard times, and we’ve been through a lot,” says Kenny. “But like Drake said: ‘We started from the bottom, now we’re here.’ ”)

Late in 2015, Kendrick released the album To Pimp a Butterfly, to critical acclaim. In its review of the album, Rolling Stone stated, “Thanks to D’Angelo’s ‘Black Messiah’ and Kendrick Lamar’s ‘To Pimp a Butterfly,’ 2015 will be remembered as the year radical Black politics and for-real Black music resurged in tandem to converge on the nation’s pop mainstream.”

Over the course of his career so far, Kendrick has received Lamar has received many award and nominations including 13 Grammy Awards, two American Music Awards, five Billboard Music Awards, a Brit Award, 11 MTV Video Music Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, and an Academy Award nomination.

His monster hit Alright was the unofficial anthem for the Black Lives Matter marches that took place throughout the world in 2016 and his soundtrack for 2018’s Black Panther movie earned him an Academy Award nomination for All the Stars, which featured guest vocals from artist, SZA. Also in 2018, Lamar made his acting debut on Starz program, Power.

Source: Rolling Stone interview, 22 June 2015