Alex Pascall: the broadcaster who gave a voice to black Britain – and is now taking on the BBC

For 14 years he interviewed stars like Bob Marley and Muhammad Ali on the first black show in British broadcasting, then co-founded the Voice newspaper, helped save the Notting Hill carnival, and starred in the Teletubbies. But has his legacy been ignored?

by Joseph Harker Thu 3 Sep 2020 06.00 BST The Guardian

Of all the places you might bump into Miss World, a bus to Finsbury Park is low on the list. But it was on the W2 in north London that Alex Pascall got one of his big breaks. “I heard a voice say to me: ‘Alex, wh’appen boy.’” When he looked up, Cindy Breakspeare, then the reigning Miss World and in a much-reported relationship with Bob Marley, was beaming back at him. Pascall had interviewed the former Miss Jamaica when she won Miss World.

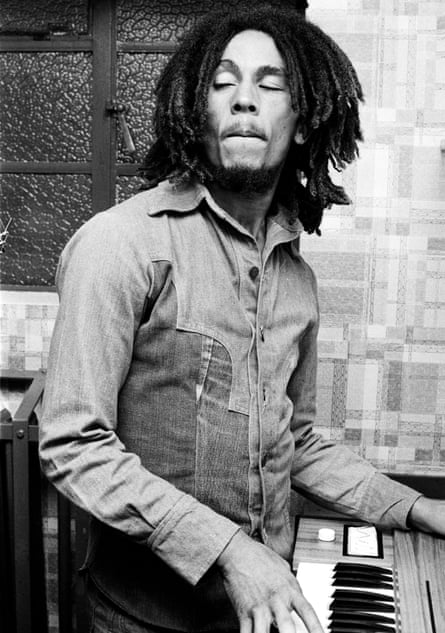

Now he was a couple of years into his groundbreaking BBC radio show, Black Londoners, and he saw a chance to contact the reggae legend. “I said: ‘I need a real interview with Bob. Help me get it.’ She said: ‘No problem, man, just give me your number and I’ll call you.’” Before long, Marley was not only on the show, but having a historic on-air meeting with the “king of calypso”, Mighty Sparrow. “The two kings” of Caribbean music, as Pascall calls them, had never met before. “Boy, when Sparrow saw Marley, I can’t tell you how great it was to watch these two men hug each other. It was a great moment.”

Creating history has come naturally to Pascall, since his birth in Grenada; his show, which ran for 14 years on BBC Radio London from the mid-70s to the late 80s, was the first black show in British broadcasting. But from his childhood in the Caribbean, to his journey to England in the 50s, to a career as a musician, to running the Notting Hill carnival, Pascall, now 83, has been blazing a trail.

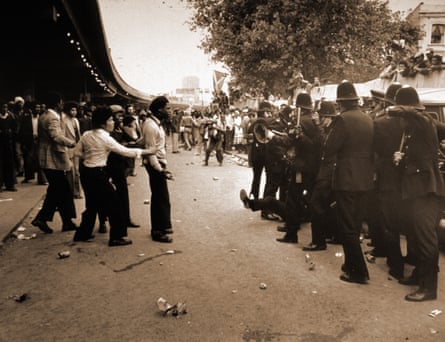

It seems incredible, but when the show began in 1974, the station chiefs doubted there was the audience or material to sustain a regular slot. Pascall was allocated just one broadcast a month. This was when Black Britain was really beginning to establish itself, despite still facing racism in the workplace, in the classroom and in law enforcement. Things came to a head during the 1976 Notting Hill carnival, when running battles broke out between black youngsters and the police. Naturally, Pascall was there to report on it. As his broadcast colleagues fled the scene, he remained. “You can’t report on something that you don’t know about – you have to be in it.” His understanding of the carnival-goers and the issues underpinning what became a major national story showcased the value of his work, and soon his show went weekly.

Alex Pascall: ‘You can’t report on something that you don’t know about – you have to be in it.’Photograph: Anselm Ebulue/The Guardian

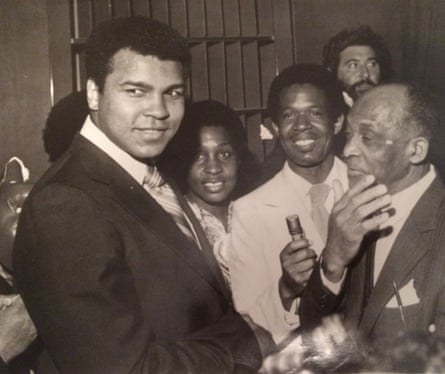

It began to attract international stars alongside community figures. Pascall’s favourite interviewee was the boxer Muhammad Ali. “I remember him wanting to hear more about the ‘sus’ laws [under which police were disproportionately arresting black people]. “One time, he recited a poem he’d written, called Truth, to me. Another time I brought a phone-in caller, who was blind, to meet him at the Grosvenor House hotel. He kept saying: ‘Where is Ali? I want to touch him.’ On being introduced, the man was overwhelmed. I could feel Ali at that moment really realising the impact he had on people. For those present, this moment of human connection was unforgettable.”

By 1978, Black Londoners had a daily slot, and Pascall’s significance became ever clearer. One survey found that his show was listened to by 59% of black Londoners, and that 60% of the station’s audience would listen to his broadcasts. Perhaps his biggest interview of that era was with Michael Jackson – then so young his schoolteacher accompanied him. His younger brother, Randy, was there, too. “Michael and Randy was oh, yo, yo … heaven,” Pascall smiles. “I just want for the rest of my life to remember the beauty of watching these two little brothers play in the studio while I’m setting up the machine. If only we had taped that bit before the actual interview, it would have been a masterpiece.”

In 1976, Pascall reported from the Notting Hill carnival when battles broke out between black youngsters and the police. Photograph: Kypros/Getty Images

In 1981, when tensions over the sus laws erupted into massive street riots, the political importance of Pascall’s show became clear. Britain’s inner cities were in flames, and the nation was stunned. “Black people from all around Britain were calling in. MPs were coming in to be interviewed. Oh, it was a time of turmoil.” Pascall believes that, by engaging with the communities and the issues at the heart of the unrest, his show helped hold the country together.

“Britain could have gone up, really. Black people were angry. The youth were angry. The elders could not deal with the children.”

Yet, he says, looking back, he is deeply unhappy with the way he and the programme were treated by the BBC; and it was the Windrush scandal that brought these feelings to the fore. The scandal horrified him; deporting black British citizens and denying them hospital treatment, or benefits they have earned, is, he says, “another form of enslavement”.

“Taking away people quietly in the night and sending them back to countries they know nothing about. Is that this human Britain, religious Britain, who sent out missionaries around the world? If that is Britain, I don’t want to be here. This is not humanity.”

The shock made him re-evaluate his own history. Despite all the groundbreaking work, his show was underfunded and he was underpaid. “It made me think, I’m no different to the Windrush people.” His solicitors are in contact with the corporation about his longstanding grievances. In 2018, the BBC said contracts of this kind used to be “standard practice”.

Pascall (centre) interviews Muhammad Ali (left). Photograph: Courtesy of Black Audio & Media Archive Alex Pascall Collection

Although Pascall has lived in Britain for more than six decades, his Caribbean identity still holds strong. He was born in November 1936, the fourth of 10 children and the oldest boy. His grandfather was a headteacher: “We would sit down by where the old sugar mill was, and he would tell me stories.” His father ran the family farm. His mother ensured he got to a good school and she developed his creativity. Every weekend she would stage storytelling and dance competitions for the family, and reward those who did well with sugar cakes she had baked. “I’d hear a song and want to sing. I’d hear a drum and want to beat.”

Pascall got to the prestigious Grenada boys’ secondary school, and his final year, at aged 19, proved to be pivotal: for a school-leaving project, he visited a so-called “poor house”, where he met people who were often written off or ridiculed. He wrote a scathing report about it, but his teacher insisted he water it down. Pascall refused. “Something came to me. I thought: if I watered the report down, it would mean, for the rest of my life, I’ll have to water everything down. I withdrew the report. And I’ve lived that way, right through my life.”

Around the same time, he won a school elocution contest and played a leading role in an island stage show, giving him confidence to take performing seriously. He worked at a warehouse to pay the bills, but within two years was playing music on stage with the Grenada Bee-Wee Ballet Dance Troupe in Trinidad, at the official event to celebrate the inauguration of the federation of the West Indies, where guests included Princess Margaret.

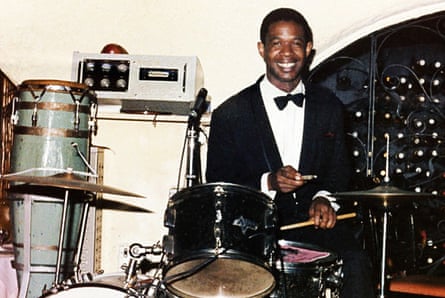

Pascall in 1969: ‘I’d hear a drum and want to beat.’ Photograph: Courtesy of Black Audio & Media Archive Alex Pascall Collection

It was an amazing experience. But his return to Grenada gave him a jolt. “Home was too small for me.” By a stroke of luck, the ballet group leader was making a documentary in London, and invited Pascall along. After arriving in London, in July 1959, the film fell through. He applied for managerial jobs without success, and eventually took a job with London Underground, first as a ticket collector and later as a train driver.

He settled in Holloway, north London, and after performing at a local talent show was soon developing his own Calypso ensemble. In 1964, he married Joyce, a fellow Grenadian. He also developed a multicultural choir, the Alex Pascall Singers. Yet one memory from that time still makes him shudder. “I was nearly killed on the Holloway bridge.” His face tightens. “I was coming out from a club and as I walked towards the bridge, I heard voices from both sides saying, ‘N-r, N-r, N-r! Get him, get him!’ They were closing in on me. “But as they got closer, a black cab turned up, the door was pitched open, and all I heard from the driver was: ‘Jump, darkie!’ I leapt in, and the teddy boys were hanging on to the door, but he managed to drive off. And when we got to the beginning of …” Pascall falls silent, takes a sharp breath and puts his hands to his eyes as they start to water. For a full 20 seconds he remains silent.

When he eventually starts to speak again, I ask what he was thinking of. “Death,” he says. And after another long pause, adds: “It’s tough.”

Gathering his thoughts, he says: “It was a white man. That’s why I always say to people, we are not all the same. No group of people are all the same.”

When he was dropped off a safe distance away, Pascall took out all the cash he had in his pocket, 10 shillings, and said to the driver: “Take it, brother, you saved my life.” The driver refused. “He said to me: ‘No, keep it. A few nights ago, if it wasn’t for some of you darkies, I would have been dead like you. They saved my life.’”

By 1981, Pascall had taken on a new challenge. He was approached by Val McCalla, then a bookkeeper in an east London newspaper office, to help set up The Voice – the first Black British newspaper, whose journalists over the years have included Martin Bashir, Trevor Phillips, Afua Hirsch and Tony Sewell. McCalla had a £7,000 grant from Hackney council, but needed to raise tens of thousands more. Pascall had a citywide reputation and useful contacts. He jumped at the chance to help.

Pascall found the funds, from the Greater London Council and from Barclays Bank, and helped market the paper. He found the launch editor, too (he had unsuccessfully approached Diane Abbott, then a reporter on Thames Television, but she told him she “had other plans”). His wife even designed the paper’s masthead. But in the days before the launch there were arguments about editorial policy with McCalla and, one day, Pascall popped out of the office for a coffee and returned to find two men barring his entry. “They had orders not to let me in.”

Pascall turned his focus back to his radio show, until, in 1984, he became chairman of the Notting Hill carnival. It was a fraught period for the festival, which since the unrest of 1976 had been seen by the authorities purely as a crime problem. The joy of the event, its significance, and the reasons it blossomed from a hall fete to Europe’s largest street party were ignored.

Pascall had seen it in the early days; it launched as an indoor event six months before he arrived in the UK. He was not immediately impressed: “I said to myself, how could a man leave Carnival back home and come and jump up inside a hall in this winter.” It eventually took to the streets of Notting Hill in the summer of 1965 and when, in the early 80s, its organisers came asking for help, Pascall made up his mind to try to save it. He linked up with carnivals across Europe and developed the children’s carnival. “By ’86 it was jumping,” he says. “But the police and the head of the council were not easy at all. Every move you made, they wanted to criminalise it.” The media coverage had also changed little. Crime, and the arrest figures – although tiny in view of the million or so attendees – dominated the reporting.

After his carnival years, Pascall returned to entertaining and teaching. He toured the country, giving talks and performances on Caribbean music and culture. And then, in the mid-90s, out of the blue came a chance to reach a huge new audience. He got a call asking to film one of his musical workshop sessions. “Within 24 hours, they called me back asking, could I be part of a programme, writing stories and music?” He said yes, “as long as I’m responsible for choosing the children, to make sure it’s a representative mix”. The show went on to become the global phenomenon Teletubbies, and he became known to millions of children worldwide for his appearances on the show, singing songs to groups of youngsters (he was also a programme consultant).

Bob Marley, whom Pascall interviewed in the 1970s. Photograph: Ian Dickson/Rex/Shutterstock

Today, Pascall hasn’t slowed down. He is an oral historian, and has just released Common Threads, an album of mixed music genres, with his daughter, Deirdre, a classical pianist. He was inspired after spending time in the mining communities of south Wales, which reminded him of the sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean. “Two commodities that have helped the British economy: sugar and coal. And two strong communities that have made Britain great.”

He still has a poise, an energy and a sharpness that belie his years, but it is clear there is a pain that still burns; he feels forgotten by the BBC, despite spending 14 years presenting a pioneering series. “I feel the BBC should have made more out of me, given the history I’ve created. Given me the chance to broadcast on mainstream radio. Because I’ve done so much for change.”

There is one moment that, for him, encapsulates the disregard with which he feels his work was treated. The morning after that historic meeting between Bob Marley and the Mighty Sparrow, Pascall, still on a high, bounded into the office. “Where’s the tape recording of last night?” he asked. No one knew. Pascall searched the office and eventually found it. It had been put in the bin.