THE BARBARISM & SAVAGERY OF FRENCH COLONISERS IN NIGER

How many times have people of African descent and origin been described by white supremacists as barbaric, savages, animals, sub-human – the list is endless. Whose behaviour and history shows irrefutable evidence of these things that they accuse us of? The answer is, all of the former invading and colonising nations.

How The Voulet-Chanoine Mission Revealed The Horrors Of French Colonialism In Africa

By Morgan Dunn | Checked By Jaclyn Anglis Published July 13, 2020

In 1898, French soldiers Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine were sent to unify colonies in Africa. But they brutalized them instead.

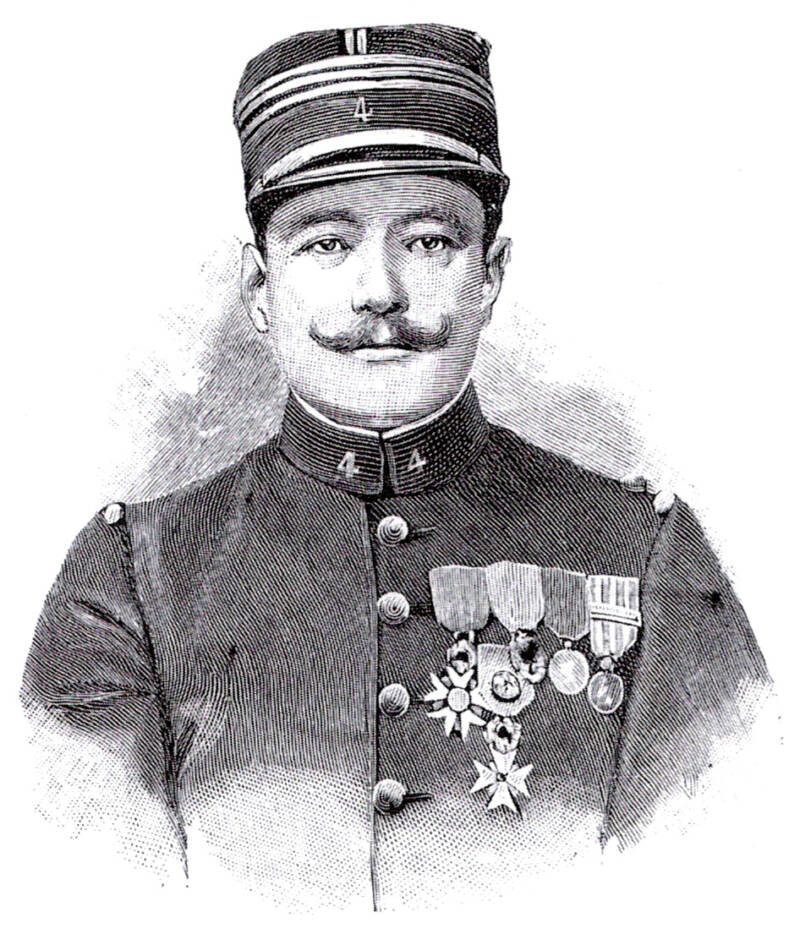

Image: Wikimedia Commons. Above: The murder of Lt. Colonel Klobb is remembered as Capt. Paul Voulet’s ultimate act of insanity that alerted France to the dangers of its empire.

Across hundreds of square miles of the Sahara in the late 19th century, two bloodthirsty French officers, Paul Voulet and Julien Chanoine, unleashed one of the most gruesome campaigns of atrocities ever recorded in the history of colonialism.

Voulet and Chanoine’s violence, as well as their gradual descent into utter barbarism, shocked even the bellicose Europe of that era, and would forever scar France’s claims that the country was on a “civilizing” mission in Africa.

Voulet And Chanoine Begin Their Expedition

Image: Wikimedia Commons. Above: Capt. Paul Voulet, the sadistic leader of the French mission whose cruelty shocked the world.

Striking out from Dakar, Senegal in the late summer of 1898, the Voulet-Chanoine Mission was to explore modern Chad and Niger, gaining valuable intelligence and hopefully reaching the Sudan to create a ribbon of French territory. Ultimately, they were expected to unify the French colonies.

But their instructions were maddeningly vague, ordering them to put the area under French “protection.”

Captain Voulet had already proven his bloodthirsty nature in the conquest of modern-day Burkina Faso. An ambitious man, he dreamed up the mission to Lake Chad as a path to the top. His second-in-command, Lt. Chanoine, was the son of a powerful general who would one day become Minister of War, making him an ideal ally for Voulet.

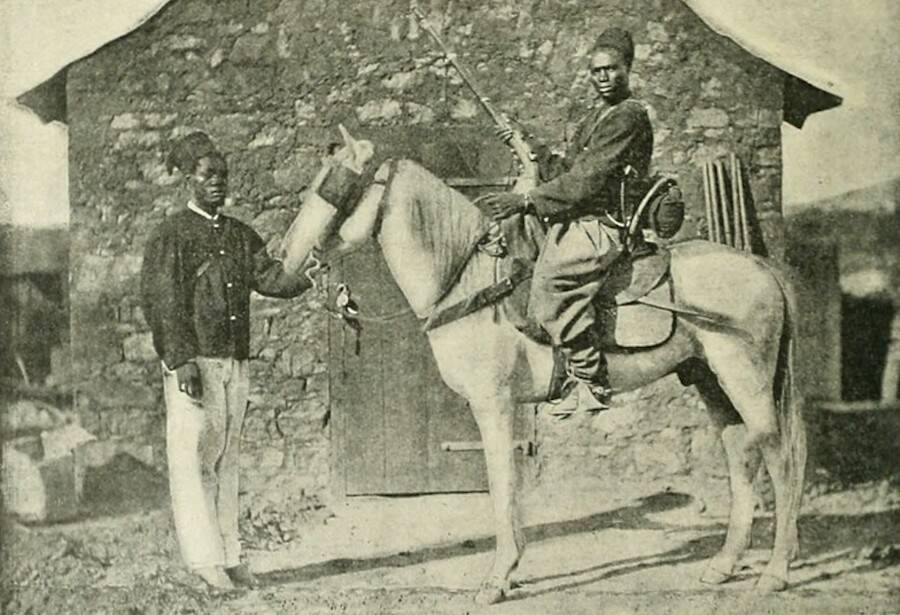

The mission did not have a promising start. Voulet wanted hundreds of French soldiers, but was forced to recruit 400 local fighters when he was given only 70 native infantry and cavalry soldiers.

His expedition was partly financed through private investors, but it wasn’t enough for the numbers he recruited, and his supplies were already strained as they passed through the desert.

To pay his hundreds of auxiliaries, Voulet promised them the only things he could: loot and slaves.

The Bloodshed Begins

Image: Wikimedia Commons: Above: Senegalese soldiers made up the professional contingent of the Voulet-Chanoine Mission.

The first part of the expedition went smoothly enough, with the column reaching the Nigerian village of Sansané Haoussa, where the force assembled in full, now consisting of 600 soldiers, 800 porters, 200 women, and 100 slaves, along with hundreds of horses, cows, donkeys, and camels.

In the middle of the desert, this group put an enormous strain on the limited supplies of food and water, sparking widespread anger and anxiety.

With his men encamped, Voulet went south to meet Lt. Col. Jean-François Klobb, an administrator of Timbuktu, who gave him an additional 70 native troopers. Klobb was nervous about Voulet, writing in his diary: “I am anxious… it seems to me that [Voulet] is venturing into something he does not know.”

Returning to Sansané Haoussa, it seems that Voulet refused to feed the huge crowd of camp followers accompanying his force. When they complained, he ordered his men to bayonet 101 men, women, and children to save ammunition, in what was to be the first of many massacres carried out during the Voulet-Chanoine Mission.

From there, the expedition carried on into other places, blazing a trail of horrific destruction. The column found that many villages had been raided by local slave-traders and their wells had been filled in, denying the French the precious water they desired.

In fury, Voulet and Chanoine ordered each village they passed to be attacked, with many villagers tortured, raped, robbed, burned, murdered, and enslaved. Locals soon knew to fear the sight of the French tricolor.

Word Gets Back To France

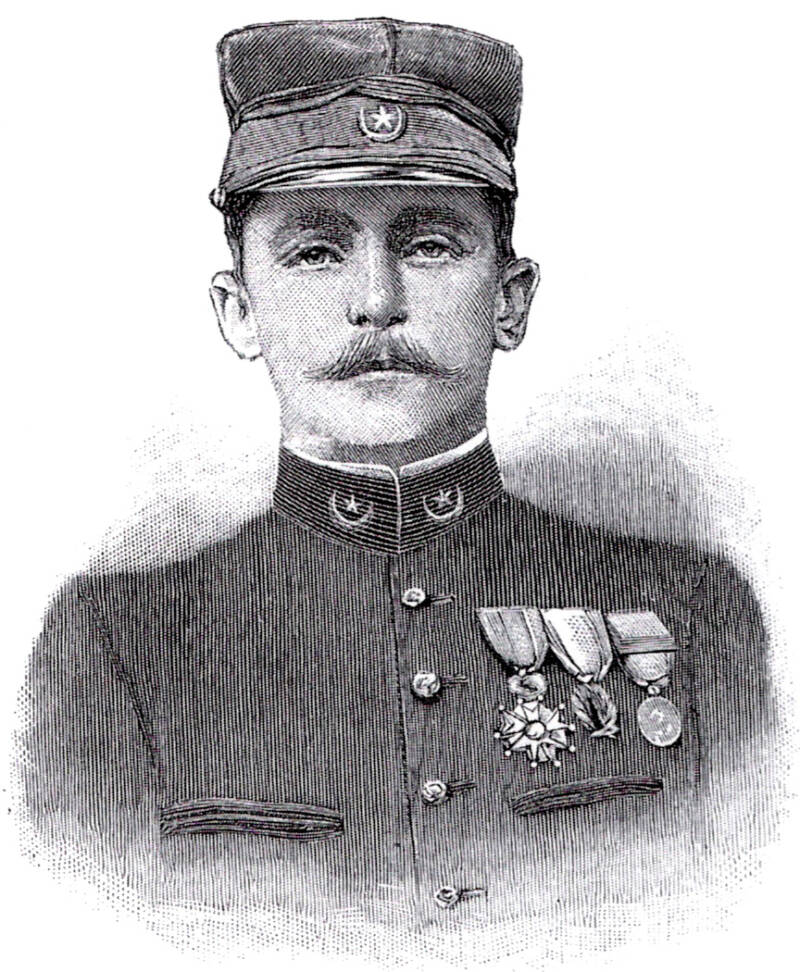

Image: Wikimedia Commons. Above: Lt. Julien Chanoine was less respected than his commanding officer, but just as willing to carry out his bizarre and terrifying schemes.

One of the mission’s junior officers, Lt. Louis Péteau, had been an eager participant in the looting and slave-raiding early on in the Voulet-Chanoine Mission.

But when he’d finally had enough and argued with Chanoine, he was dismissed and ordered to return to France. On his way back, Péteau wrote a 15-page letter to his fiancée describing the atrocities he’d seen.

He described how porters who were too weak from dysentery to move had been refused medicine and were often beheaded and replaced with enslaved locals.

To make matters worse, Voulet had ordered the severed heads to be placed on stakes to terrify nearby villagers. Péteau also revealed the horrific truth behind the massacre at Sansané Haoussa, relating how the people there had been murdered despite their chieftain giving into every French demand.

Péteau’s letter soon made its way to Antoine-Florent Guillain, the Minister of Colonies, who immediately telegraphed orders to have Chanoine and Voulet arrested:

“I hope the allegations are unfounded — if against all probability these abominable crimes are proven Voulet and Chanoine cannot continue to lead mission without a great shame for France…”

Klobb’s Pursuit And Voulet’s Treason

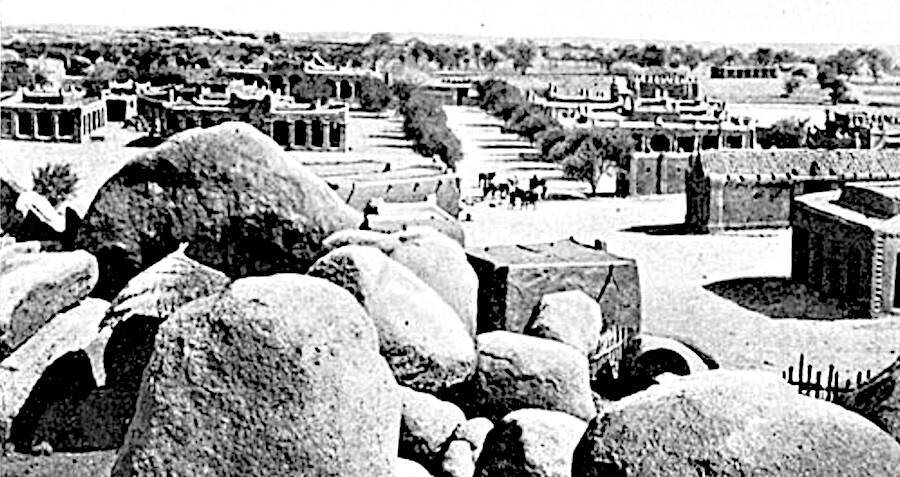

Picture: Wikimedia Commons. Above: Zinder, Niger, outside of which the fateful meeting of Voulet and Klobb took place.

Leading the pursuit was Lt. Col. Klobb, the administrator of Timbuktu. His journey was preceded by a letter ordering Chanoine and Voulet to surrender themselves, but the two officers kept the letter secret from their subordinates.

The experienced Klobb made rapid progress in finding them. Although Voulet and Chanoine had a year’s head start, Klobb had spent more than 10 years in Africa, much longer than any other officer of the time.

Supported by a small group with little baggage, Klobb caught up to the column by mid-July 1899, following their literal trail of destruction. In his diary on July 11, he wrote:

“Arrived in a small village, burnt down, full of corpses. Two little girls hanged from a branch. The smell is unbearable. The wells do not provide enough water for the men. The animals do not drink; the water is corrupted by the corpses.”

On July 13, Voulet had 150 women and children from a local village murdered, ostensibly to avenge the death of two of his own men who were killed during a raid in a separate nearby village. On July 14, Bastille Day, just outside the town of Zinder, Klobb finally found Voulet.

Approaching alone and unarmed, Lt. Col. Klobb had given orders to his party not to open fire under any circumstances. Voulet demanded that Klobb turn around, but Klobb refused. So Voulet ordered his men to fire two salvos. Klobb was killed and his soldiers fled.

The Downfall Of Voulet And Chanoine

Later that day, Voulet stripped off his badges of rank and gave a bizarre speech to his officers:

“Now I am an outlaw, I disavow my family, my country, I am not French anymore, I am a black chief. Africa is large; I have a gun, plenty of ammunition, 600 men who are devoted to me heart and soul.”

“We will create an empire in Africa, a strong impregnable empire that I will surround with deserted bush… If I were in Paris, I would be Master of France.”

Chanoine responded with enthusiasm, but the other officers quietly slipped away, certain that Voulet had lost his mind. The soldiers, reluctant to obey Voulet now that he’d removed his insignia and fearful of what might happen to their families if they followed him, revolted.

They quickly overpowered Voulet’s few loyalists, and Chanoine was killed by seven bullets and two saber cuts. Meanwhile, Voulet was chased out of the camp, taking refuge in a nearby village. When he tried to come back to his troops, he was shot and killed by a sentry.

Image: Wikimedia Commons. Above: Lt. Paul Joalland, who completed the Voulet-Chanoine Mission, would later go on to have a colorful military career, serving in French Indochina and World War I.

Lt. Paul Joalland was the sole officer left in charge. Joined by the loyal Senegalese troops and Klobb’s second-in-command, he completed the original mission, linking up with the other two Saharan expeditions to defeat Rabih az-Zubayr and secure the region for France.

But in the years following, the mission would forever taint France’s image in terms of colonialism. Ultimately, the expedition served as a warning of what could happen when people were placed at the mercy of Europeans who were capable of unspeakable cruelty.

Source: https://allthatsinteresting.com/voulet-chanoine-mission

Further research: Exterminate All The Brutes by Sven Lindquist (book)

Arena: African Apocalypse, documentary film by Femi Nylander

Exterminate All The Brutes, documentary series by Raoul Peck

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (book)