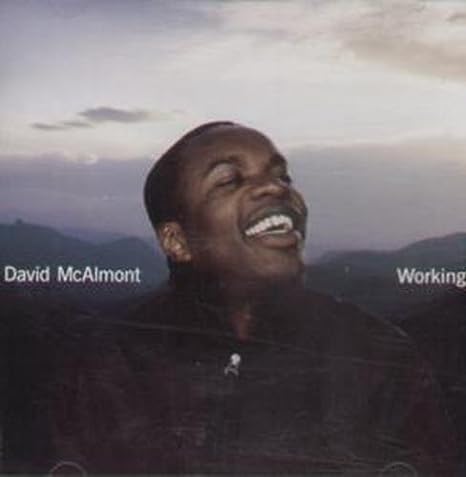

DAVID McALMONT

April 5, 2021

David McAlmont was born in Croydon in 1967, but had a transatlantic upbringing, living in the UK until he was 11 years old, and then moving to his mother’s birthplace of Guyana, on the northeastern seaboard of South America. Leaving behind a Britain in political ferment, and still in the throes of the punk upheaval, he underwent a wholesale cultural reorientation, in a period of his life that contained and has remained a rich mix of musical influences.

In the Guyana of the late 1970s and early 1980s, the radio shows played the latest American pop (Prince, Whitney Houston), as well as vintage soul, the close-harmony stylings of the Lettermen, and even earlier golden oldies from the era of Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Peggy Lee. Most people had no television, and so voices were very much just that, disembodied from any visual impression of their owners. A teenager hearing Boy George and Culture Club on the radio singing ‘Do You Really Want To Hurt Me?’ was in for something of an awakening when he first clapped unsuspecting eyes on the singer. The same might equally be true, for different reasons, of Phil Collins.

David recalls being mightily impressed by R&B veteran Melba Moore’s trademark big-screen finish to a song, in which she would hold the final note in a triumphant sostenuto that might go on for fully 40 seconds. It’s a technique he appropriated in his own live performances, always producing a rapturous response.

U Got The Look

Just as the previous generation of British-born kids had got through their grim teenage years with the aid of David Bowie in his Ziggy Stardust period, so for young McAlmont, the sustaining helpmeet of a conflicted adolescence was Prince, the dramatically flamboyant Prince of Purple Rain (1984). He cheerfully acknowledges that his own early image would go on to owe a lot to Prince. ‘I was wearing purple crushed velvet,’ he recalls with a knowing chuckle. To a half-Nigerian, half-Guyanese teenage boy back in high school, Prince’s look was the first indicator that he didn’t necessarily have to be what he was expected to be.

Cutting across that current was church, both musically and spiritually. There was the traditional Christian music of Mahalia Jackson, Shirley Caesar and the great gospel shouter James Cleveland, as well as a newer strain in the shapes of Andraé Crouch and the wildly popular Amy Grant. ‘They didn’t sound like the sort of thing you would hear in church,’ David says. ‘When I listen to that music now, I have to confess, it’s with a mixture of nostalgia and revulsion, but at the time, once again, it was something different. That’s what my career has always been about really. I never wanted to conform, fundamentally because I couldn’t.’

The inability to conform was to see David break with his faith. Although he continued to attend a Pentecostal church after he moved back to the UK, at around the time of his twentieth birthday, the relationship was becoming increasingly troubled. In due course, he left the church because, in its depthless wisdom, it failed to show him any way of reconciling his spirituality and his sexual identity.

Both Sides of the Story

If the move to Guyana had opened up new horizons, David’s return to Britain in 1987 involved even more of a jolt, not least musically. Coming back to British pop as some kind of outsider was at once a baffling and productive challenge. The famous tribalism of British youth culture, which even now has no precise analogues in the Americas, was a phenomenon that he was peculiarly well-placed to observe, the more so since he had spent equal parts of his life to date in both cultures.

‘There’s a certain shape to musical appreciation in this country that I don’t have, and that I didn’t immediately understand. A lot of the music I’ve heard here since then has been an education, and I’ve had to come to understand the significance of musical history in Britain, which is really important to people.’

The British experience, in which a measure of defiant group allegiance is mixed in with any notion of actual enjoyment, owes its existence to the fact that UK pop has been nothing if not a series of ideological movements. It was a mixture that the punk revolution brought into even sharper focus than ever before. In Guyana, people listened to music they found pleasing, purely and simply. ‘I was listening to so many great singers on the radio, who I liked, and I didn’t have a sense of cheese at all, even though I was listening to a lot of it. Then I came back here, and found people appreciated a lot of things that are not necessarily a pleasure to the ear, in a way that would be quite alien to Guyanese listeners. That was a real eye-opener for me.’

It was an education that was to proceed through David’s earliest press interviews, where mention of Phil Collins was probably best left at the door. ‘Don’t forget I’d gone from seventies Top of the Pops to Guyanese radio. I heard him doing great songs on the radio over the years, then I come back to England and find that he’s thought of this evil dwarf who destroyed Peter Gabriel’s band, and that people are passionate about that to the point of apoplexy.’

You Can’t Hurry Love

What could the Britain of the late eighties offer a young man making a kind of return? ‘I did have a five-year plan. I intended to be part of a musically significant band by then.’

In the meantime, there were day-jobs. Anybody making a liability claim to the Croydon branch of the SunAlliance insurance company in 1987 may have had their paperwork processed by David.

Moving out of his aunt’s house to Thornton Heath and then Streatham Hill, he began to view his sexual identity as something more than just a spiritual cross he had to bear. If the unrepentant were truly bound for Hell, it turned out to be a place called Swiss Cottage.

‘Through the gay section in Time Out, I met somebody in north London, fell in love with him and moved up there.’

Through The Door

So to the million-dollar question. Where does a career in music actually begin? What doors do you need to get your foot into, and how?

While taking a BA course in Performance Arts at Middlesex University, David answered an ad in the now-vanished trade paper Melody Maker: ‘Singer wanted for band. Black/white, male/female, gay/straight, doesn’t matter.’ ‘I thought that sounded like me,’ he laughs.

The band was Thieves, a duo with multi-instrumentalist Saul Freeman, and it achieved its first traction via the same route with which David had joined it. ‘We sent the flyer for our first appearance at the Bull and Gate in Kentish Town to Dave Simpson at Melody Maker. He came to see us, liked what he saw and wrote a review for the paper, in which they printed my address.’

Within days, there were calls, one of the first from a short-lived early-nineties fanzine called Ego Bruising, edited by Clive Gabriel. He had just been offered a job as A&R scout at the Chrysalis label, and the company duly signed Thieves in 1992. Simple, really.

Except not really. Thieves released a trio of highly acclaimed singles, ‘Through The Door’ (1992), ‘Unworthy’ (1993) and ‘Either’ (1994), and began work on their debut album. The sound was a very of-its-moment postmodern amalgam of references, drawing on classic soul grooves (Marvin Gaye was much mentioned in the reviews), English alt-pop and film soundtrack samples, while the image was crafted to perfection. Not since Depeche Mode escapee Vince Clarke added Alison Moyet’s pulsing soul vocal to a background of dweebling machine-pop had a more dialectically productive combination of musical presences been achieved.

David looked and sounded utterly startling, in a way that genuinely shook many commentators out of the seen-it-all complacency of an era now saturated in rap and hip-hop. He rapidly established a reputation for transcendent vocal pyrotechnics that was difficult to compare with any other singer. ‘One day he will open his mouth,’ the music critic Taylor Parkes predicted, ‘and a cathedral will fall out.’

For the time being, what fell out was the Thieves debut album. The band split in 1994, just as its release was imminent. After much legal entanglement, it was eventually released as McAlmont, by which time it already marked the closing of an initial chapter.

The Right Thing

Following the album’s release, David went on tour with a replacement band supporting the likes of Cyndi Lauper and Lisa Stansfield, but it’s fair to say that recognition beyond the pages of the Melody Maker wasn’t readily forthcoming.

Then one of those chance occurrences with which music history is scattered came about. While nobody could have foreseen its significance at the time, the departure from indie giants Suede of the band’s first guitarist, Bernard Butler, was just such an occurrence. Butler’s manager Geoff Travis took his protegé to the Jazz Café to see David perform, suggesting that they might consider working together. The initiative had further been activated by a chance comment David had made, when somebody at Glastonbury asked him what he thought of Suede (then being officially touted as the best new band in Britain), and he had replied that he thought the best thing about them was their guitarist.

The prime impetus for this most improbable of connections derived from the fact that Butler had been writing some material in the spirit of Dusty Springfield, and he was looking for a suitable singer to take it on. One particular track had been sent to Morrissey, Julianne Regan, vocalist with All About Eve, and Kirsty McColl, who had all turned it down, before it entered David’s field of vision. ‘I remember I just leapt at it, I thought it was such a great song.’

‘Yes’, McAlmont and Butler’s first single and a No 1 hit, was the first encounter that many of us had with David. Released in 1995, its impact remains undimmed by the years. If it sounded sublime on the radio, it was altogether jaw-dropping on Top of the Pops, where David’s now legendary appearance with bright blue lips and flying dreads magnified what was already a Force 10 gale of a song into a tornado. It is a prime example of a minority sub-genre within pop history, the song of withering contempt. It was a mode Bob Dylan had cornered in the sixties, but this was a world away. From its very first line, ‘So you want to know me now?’, it was the sound of a star not so much arriving as busting open the door and knocking the teacups over.

Fittingly, not long before recording it, David had seen the great Judy Garland tour de force, A Star Is Born. Something of the feel of the movie’s key song, ‘The Man That Got Away’, allied to a recent experience with a dream date that had gone all nightmare on him, fed into the lyric and, supremely, the performance of ‘Yes’. ‘It was very fortunately timed,’ recalls David. ‘There was a view of Bernard that he was a genius, and everybody was very keen to see what his next move would be. While the word on me that I was a great vocalist who hadn’t found his song yet. When we were put together, people expected some sort of spark, and ‘Yes’ provided that spark. People just loved it.’

You’ll Lose A Good Thing

The album that followed, The Sound of McAlmont and Butler, didn’t disappoint. From its unwittingly clever cover, which shows the two boys looking in entirely different directions, Bernard to the heavens, David off to the left, as though they haven’t yet met each other, to the succinct set of eleven great songs, it was an engagingly confident debut. David acknowledges Prince’s presence as a presiding influence in much of it (perhaps most evident on ‘What’s The Excuse This Time?’), and its closer, the panoramic, immaculate ballad ‘You Do’, was the duo’s next hit.

And then, just as everything was as glistening with promise as with a coat of day-glo paint, trouble set in. A spate of over-publicised, and inaccurately publicised, spats between the two had broken out even before the release of ‘You Do’. When they arrived at the Top of the Pops studio in separate cars (logically enough, as they had come from separate addresses), there was talk. Sadly, none of this talk was going on between the two principals. David didn’t entirely help by giving a ‘stroppy interview’ in which he appeared to call into question Bernard’s attitude to his, David’s, sexuality, and suddenly it was over. After one live appearance and one now posthumous album.

Who Loves You?

Notwithstanding the demise of McAlmont and Butler, David found himself being swept up in the Cool Britannia atmosphere of the mid-1990s. ‘I was being invited to all the parties, and I was going to all the parties, and doing the things that came with partying. At the same time, I began writing an album that was all about the emotions I was going through as a consequence of the partying.’

Asked to contribute a track to an album of Bond theme covers, Shaken and Stirred, by the film composer and producer David Arnold, David recorded a glittering rendition of ‘Diamonds Are Forever’, drawing every last scintilla of drama out of the soaring melody.

The collaboration was a sympathetic one, and Arnold seemed the obvious choice to produce the album of new material David had been writing. What was eventually released as his first solo album, A Little Communication(1998), is not, however, the Arnold production. It was felt that the big cinematic treatment Arnold gave the tracks didn’t exactly suit them, and the album was recorded from scratch with Tommy Dee at the desk.

What resulted was a much more intimate-sounding collection, the tone set by a wistfully reflective opener, ‘Lose My Faith’, and continuing through the breakout classic ‘Who Loves You?’, to the gentle, breezy regret of ‘Sorry’. It established David as a much subtler, torchier singer than the bangers and sparklers of the work with Butler might have indicated. It’s a record that David still feels has been critically underrated, as was evidenced by the Jazz Café gig in 2008 with which he marked the tenth anniversary of its release.

Bring It Back

In the aftermath of that, David recorded an album entitled simply B, which never saw the light of day. He describes it as a ‘very positive, poppy, soulful record’. One single, ‘Easy,’ inspired by the prevalent drum-and-bass sound of the period was released from it, as much to tap into the suddenly huge Craig David market as anything else. Garage producer and DJ Sweet.P! was then brought in to remix a track called ‘Working’, after which the record company, Hut, felt that reworking the entire album would be a good idea. David didn’t much fancy that, another parting of the ways arose, and the record was buried.

One afternoon, David received out of the blue a call from Bernard Butler, asking what he was doing. ‘He’d been writing some material and thinking about me, and he suggested we should have a meeting and talk about doing a new record. We met up, sorted out what had gone on in the past, and set about recording it.’

The second McAlmont and Butler album, Bring It Back, was released on EMI in 2002. It was critically well-received, and produced a Top 20 hit in the shape of ‘Falling’, arguably the duo’s best collaboration after ‘Yes’. Blessed with the kind of fabulous, soaring tune David was born to sing, the lyric gives an eagle’s-eye view on a moment of ecstatic romantic possibility that throbs achingly through a killer refrain, ‘If you take my hand, you can take command,’ The album’s title track followed it as a single release, but so did some by now familiar bad luck.

When the A&R man who had signed them to EMI lost his job, he was replaced by somebody who wasn’t at all convinced of the commercial potential of the project. The duo stayed with the label for another year until they were belatedly dropped, by which time Butler had responded to an overture from former Suede frontman Brett Anderson to record some more material together.

Blues in the Night

The period immediately following Bring It Back was one of uncertainty and redefinition. It’s hard to know what becomes of a recording career when music publishers themselves can’t make up their corporate minds about you. This was a time when neither David nor his tenacious cohort of followers seemed quite sure what it was he ought to be doing. The appearance on the scene of a benefactor who undertook to fund his future recordings had something of the flavour of a plot development in nineteenth-century fiction, the more so when it turned out that the promised funding would eventually disappear like autumn mist without David being quite aware that it had.

He recorded a couple of one-off collaborations during this interlude. ‘Snow’ was a track on film composer Craig Armstrong’s second solo album As If To Nothing (2002). They toured the album to France and Belgium, David also contributing to proceedings a version of the revered Randy Crawford classic, ‘One Day I’ll Fly Away’, which had recently been featured in Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001). In 2003, a sensitive reading of John Martyn’s ‘Bless the Weather’ for Courtney Pine’s Devotionwas singled out in many reviews as one of the highlights on what is often held to be the jazz legend’s finest album.

What eventually emerged from this period of retrenchment was an album from David that set one possible new course. As he puts it, he had been considering for a while the possibility of making an album for his mum. She had periodically suggested to David that he ought to sing some of the jazz standards that he had loved hearing on Guyanese radio all those years ago. Set 1: You Go To My Head, released in 2005, was the result.

The album drew on the best traditions of intimate jazz recording. Had Norman Granz been living at this hour, he would have snapped it up. It is imbued with the feel of the classiest sessions released on Granz’s Verve Records in the 1950s, a potent late-night blend of tenderness and grown-up seriousness. Did jazz aficionados ever feel they needed another ‘Night and Day’? Another ‘Under My Skin’, or another reading of the title track? David evokes unexpected new depths from these familiar lyrics, with the consummate singer’s knack of making us hear them as though for the first time. Never, at least since Billie Holiday recorded it for Verve in 1957, has the opening line ‘It’s quarter to three,’ sounded so, well, quarter-to-threeish. And then dropped like a pebble into the surrounding nostalgia is the blissful, daring anachronism of Whitney Houston’s biggie, ‘Saving All My Love For You’. The interpretation hints, tantalisingly, at what Billie would have made of it.

One More For The Road

Tiresomely, but now almost inevitably, the label that put out Set 1, Ether, collapsed at the end of that year. David found belatedly that he didn’t have anything resembling a contract. Another chapter was prematurely closed.

He floundered for a couple of years, doing a few shows here and there ‘to keep my face in’, recording some thoughtful contributions to TV documentaries, including a BBC tribute to Ella Fitzgerald. One branch of his current multi-faceted live operations was to develop at this time, though. In a foyer space at London’s Royal Festival Hall, during a run of The Wizard of Oz, he performed a set of Harold Arlen songs to simple keyboard backing, which has become an integral part of his live repertoire.

‘Blues in the Night’ and ‘One For My Baby’ had featured on Set 1, but to these David has added readings of ‘That Old Black Magic’, ‘It’s Only A Paper Moon’, ‘Accentuate the Positive’, ‘Get Happy’ and, of course, ‘Over The Rainbow’, tailored to display his formidable vocal range. There are richnesses of timbre as well as extravagant leaps of pitch in these performances, which go beyond simple (simple!) technical virtuosity to draw audiences close with their warmth and humanity. David lets the wit in certain of the lyrics speak for itself, as much as the hopeless yearning in certain others. Like the best interpreters, he surrenders himself to the lyric and melody, and thereby invites us to join him in the surrender. His justly celebrated falsetto range, once deployed to dramatic effect against Butler’s thrashing guitar, turns out to have no apparent need of such histrionics, but floats up into a stratosphere of its own where, even in the noisiest and booziest of live venues, it proves as iridescently impossible to ignore as the fluttering of hummingbirds.

After Youth

There is now a feeling that David McAlmont is entering on the most fertile phase of his career. His heterogeneous range of musical activities has taken wing against the background of a degree of self-management in his personal life that doesn’t often come easily to celebs once used to partying like it was going out of fashion. He doesn’t use intoxicants of any description, with the exception of the odd strategic cup of caffeinated coffee. Those who know him can see a man far more at ease with himself, with confidence and ambition untarnished.

David has said that he would like to continue developing what might be thought of as the Songbook approach in his live appearances. In the 1950s and 60s, Ella herself made a series of records devoted to the works of the great songwriters, from Cole Porter to the Gershwins. David has his eye on a Rodgers and Hart show, and maybe one based on Billie’s classic tracks. Our cards have been marked.

Next up, though, is one of his most extraordinary collaborations to date, with composer Michael Nyman. Their album, The Glare, is released in late October 2009, and promises to mark another step-change in David’s career.

In impeccably postmodern fashion, the two met on a social networking website, when Nyman contacted him to see whether he would be interested in working together. ‘I’m far too postmodern to write about feelings,’ said the composer of acclaimed scores for such films as Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989) and Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993). This chimed with David’s professed disinclination to ‘continue writing about me’, and the songs on the album refer instead to a range of contemporary issues, from the imprisonment in Laos of British tourist Samantha Orobator on a drug-smuggling charge to aftermath of the bombardment of Gaza and the ordeal by television of Susan Boyle. The songs ally Nyman’s signature style of bustling, densely textured string rhythms with some of David’s most poignant singing, as they tell the stories of the modern world’s generally overlooked casualties.

There is compassion and a deep sense of empathy in these new tracks. And that’s where David McAlmont’s singing has always come from.

Source: davidmcalmont.co.uk

Like

Recent posts

Papal Bull of 1455, Romanus Pontifex

This Bull authorised Portugal to raid African Kingdoms, territories and land, capture and enslave the inhabitants and seize their natural and mineral resources, under the authority of the Pope and the Catholic Church.

The Reign of Elizabeth II

A summary of the reign of Elizabeth II and events that took place during her reign

Previous post

KEMI BADENOCH

Next post

BRUCE OLDFIELD