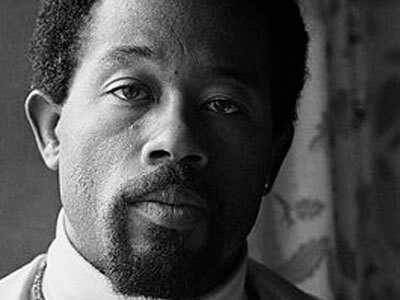

ELDRIDGE CLEAVER

Leroy Eldridge Cleaver was born in Arkansas, on August 31, 1935, to Leroy Cleaver, a waiter and piano player in a local nightclub, and Thelma Cleaver, an elementary school teacher. When the father became a waiter on the Super Chief train, the family moved to Phoenix, a stop on the train’s run from Chicago to Los Angeles. Mr. Cleaver later said that his father often beat his mother and that soon after the family moved to the Watts section of Los Angeles, his parents separated.

Mr. Cleaver had barely started Abraham Lincoln Junior High School — where his mother was a janitor — when he was arrested for bicycle theft and sent to reform school, where the older boys inspired loftier ambitions. Almost immediately after his release, he was sent to another reform school, for selling marijuana. A few days after he was released from that school, he was arrested for marijuana possession, and made the big time: two and one half years at Soledad state prison.

He began reading widely and received his high school diploma at Soledad, forming, he wrote in ”Soul on Ice,” ”a concept of what it meant to be black in white America.” But a year later Mr. Cleaver was arrested for his rapes, convicted of assault with intent to murder and sent first to San Quentin prison and then Folsom for a term of 2 to 14 years.

He became first a jailhouse Black Muslim convert, then after the split in the Nation of Islam followed Malcolm X. In mid-1965, eight years into his term, he wrote to Beverly Axelrod, a well-known white civil liberties lawyer in San Francisco asking for help in pleading for parole.

Ms. Axelrod took his essays to Edward M. Keating, Rampart’s owner and editor. When Mr. Cleaver went before the parole board, he was a published writer with the support of literary lights like Mr. Geismar, Norman Mailer and Paul Jacobs.

Freed in December 1966, with a job reporting for Ramparts in San Francisco, Mr. Cleaver helped organize Black House, a cultural center, where he met Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the co-founders of the Black Panther Party, which they called an organization for ”self-defense” against the police.

Freed from Prison With a Radical Goal

The Panthers were a growing presence in Oakland, shadowing police patrols, whom they accused of brutalizing the black community, and openly displaying weapons. Mr. Cleaver quickly joined the party as minister of information — chief spokesman and propagandist.

”We shall have our manhood,” Mr. Cleaver declared. ”We shall have it or the earth will be leveled by our attempts to gain it.”

Mr. Cleaver also began teaching an experimental course at the University of California at Berkeley in fall 1968, which infuriated then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, who declared, ”If Eldridge Cleaver is allowed to teach our children, they may come home one night and slit our throats.”

At the time, Mr. Cleaver regularly referred to Mr. Reagan as Mickey Mouse in his speeches. It is a measure of Mr. Cleaver’s many changes that in 1982 he was booed and hissed by the Yale Afro-American student society for supporting Mr. Reagan.

In the black leather coat and beret the Panthers wore as a uniform, Mr. Cleaver was a tall, bearded figure who mesmerized his radical audiences with his fierce energy, intellect and often bitter humor.

”You’re either part of the problem or part of the solution,” he challenged, in one of the slogans that became a byword of the era.

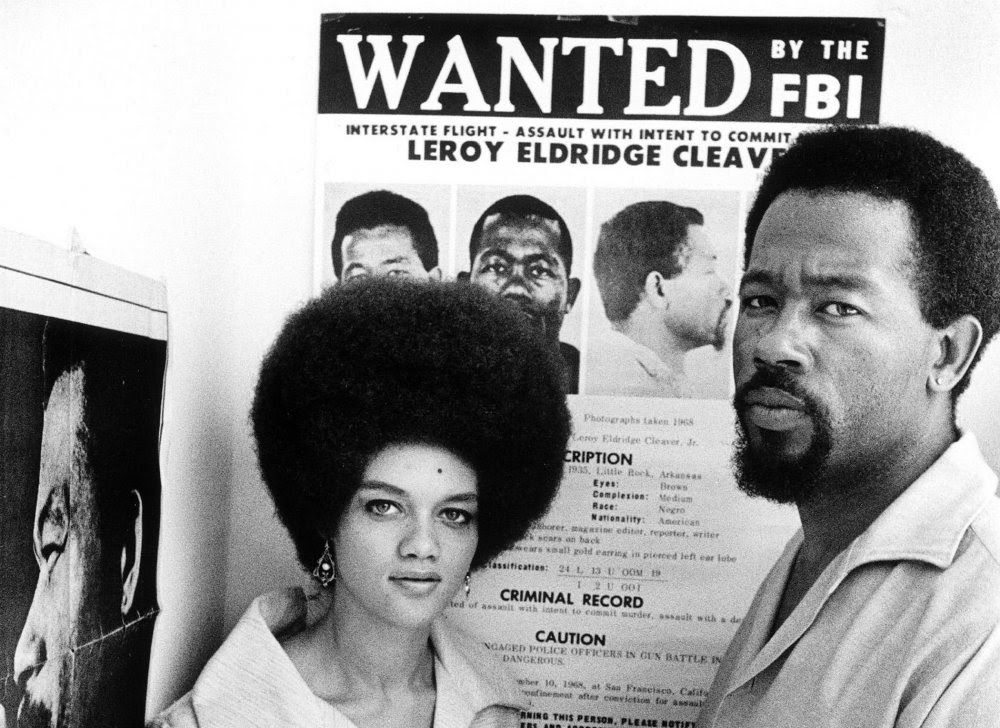

He became even more of a symbol when he jumped bail after a shootout between Black Panthers in Oakland, Calif., and the police and fled into exile in Cuba and Algeria, adding the causes of Communism and third world liberation to his repertoire.

But after he returned to the United States in 1975, Mr. Cleaver metamorphosed into variously a born-again Christian, a follower of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, a Mormon, a crack cocaine addict, a designer of men’s trousers featuring a codpiece and even, finally, a Republican.

‘Soul on Ice,’ Memoir as Manifesto

When ”Soul on Ice,” was published in 1968, it had a tremendous impact on an intellectual community who finally saw hope in the civil rights movement, urban riots, the war in Vietnam and campus rebellions. It was a wild, divisive time in the United States, and Mr. Cleaver’s memoir from Folsom state prison, where he was doing time for rape, was hailed as an authentic voice of black rage in a white-ruled world. The New York Times named it one of its 10 best books of the year.

”Cleaver is simply one of the best cultural critics now writing,” Maxwell Geismar wrote in the introduction to the McGraw-Hill book, adding:

”As in Malcolm X’s case, here is an ‘outside’ critic who takes pleasure in dissecting the deepest and most cherished notions of our personal and social behavior; and it takes a certain amount of courage and a ‘willed objectivity’ to read him. He rakes our favorite prejudices with the savage claws of his prose until our wounds are bare, our psyche is exposed, and we must either fight back or laugh with him for the service he has done us. For the ‘souls of black folk,’ in W. E. B. Du Bois’s phrase, are the best mirror in which to see the white American self in mid-20th century.”

First printed in Ramparts, the quintessential radical magazine of the 60’s, Mr. Cleaver’s prison essays are angry, sometimes bitingly funny, often obsessed with sexuality. And they trace the development of his political thought through his prison readings of the works of Thomas Paine, Marx, Lenin, James Baldwin and, above all, Malcolm X.

”I have, so to speak, washed my hands in the blood of the martyr Malcolm X,” Mr. Cleaver wrote after the assassination of the onetime Black Muslim leader who had moved away from separatism, ”whose retreat from the precipice of madness created new room for others to turn about in, and I am caught up in that tiny space, attempting a maneuver of my own.”

But it was a difficult space to reach. In one of the book’s most gripping and brutal passages, he wrote:

”I became a rapist. To refine my technique and modus operandi, I started out by practicing on black girls in the ghetto — in the black ghetto where dark and vicious deeds appear not as aberrations or deviations from the norm, but as part of the sufficiency of the Evil of the day — and when I considered myself smooth enough, I crossed the tracks and sought out white prey. I did this consciously, deliberately, willfully, methodically — though looking back I see that I was in a frantic, wild and completely abandoned frame of mind.

”Rape was an insurrectionary act. It delighted me that I was defying and trampling upon the white man’s law, upon his system of values, and that I was defiling his women — and this point, I believe, was the most satisfying to me because I was very resentful over the historical fact of how the white man has used the black woman. I felt I was getting revenge.”

There was little doubt he went on, citing a LeRoi Jones poem of the time which expressed similar rage, ”that if I had not been apprehended I would have slit some white throats.” But he was caught, and after he returned to prison, Mr. Cleaver wrote:

”I took a long look at myself and, for the first time in my life, admitted that I was wrong, that I had gone astray — astray not so much from the white man’s law as from being human, civilized — for I could not approve the act of rape. Even though I had some insight into my own motivations, I did not feel justified. I lost my self respect. My pride as a man dissolved and my whole fragile moral structure seemed to collapse, completely shattered.

”That is why I started to write. To save myself.”

As tensions between the Panthers and the authorities rose, Mr. Cleaver was caught up in a shootout in April 1968 in which a 17-year-old Panther, Bobby Hutton, was killed and Mr. Cleaver and two policemen were wounded. Facing the revocation of his parole and new charges, Mr. Cleaver jumped a $50,000 bail late that year and fled into exile, first to Cuba and then to a home in Algeria, then a leftist haven.

Mr. Cleaver married Kathleen Neal in 1967, the daughter of Foreign Service officer. She followed him to Algeria, and they had two children, a son, Maceo, now 29, and a daughter, Joju, 28. The couple divorced in 1987, and Mrs. Cleaver is now a lawyer and teacher.

At first Mr. Cleaver toured Communist countries triumphantly, hailing Kim Il Sung of North Korea, among others. But disillusion set in, and there was increasing friction between the Algerian Government and Mr. Cleaver’s entourage. There was an internal struggle between Mr. Cleaver and Mr. Newton, too, and Mr. Cleaver broke with the Panthers in 1971.

Spiritual Awakening And Surrender to F.B.I.

”I had heard so much rhetoric about their glorious leaders and their incredible revolutionary spirit that even to this very angry and disgruntled American, it was absurd and unreal,” Mr. Cleaver wrote later,

The family moved to France. There, Mr. Cleaver said, contemplating suicide one night with a gun in his hand, he suddenly had a vision in which his old Marxist heroes disappeared in smoke and a blinding light led him to Christianity. In 1977, he returned to the United States and surrendered to the F.B.I. under a deal with the Government by which he pleaded guilty to the assault charge stemming from the shootout. Charges of attempted murder were dropped, and he was sentenced to 1,200 hours of community service.

But, Mrs. Cleaver said in a 1994 interview with The San Francisco Chronicle, ”he came back a very unhealthy person, unhealthy mentally, and I don’t think he’s ever quite recovered. He became a profoundly disappointed and ultimately disoriented person.”

Mr. Cleaver drifted in his enthusiasms. He opened a boutique for the trousers he created featuring what he called the Cleaver sleeve. He embraced various religions. He ran a recycling business for a while, but other recyclers accused him of stealing their garbage. He was treated for addiction to crack cocaine in 1990. A crack charge two years later was dropped because of an illegal search, but in 1994 Berkeley police found him staggering about with a severe, never fully explained, head injury and a rock of crack in his pocket. He proclaimed himself a conservative and ran, unsuccessfully, for various local offices as a Republican.

His political turnabout was such that, in the 1980’s, he demanded that the Berkeley City Council begin its meetings with the Pledge of Allegiance, a practice they had abandoned years before.

”Shut up, Eldridge,” Mayor Gus Newport told the man who had once been the fiercest emblem of 1960’s radicalism. ”Shut up or we’ll have you removed.”

Eldridge Cleaver, whose searing prison memoir ”Soul on Ice” and leadership in the Black Panther Party made him a symbol of black rebellion in the turbulent 1960’s, transitioned to become an ancestor on May 1, 1998 in Pomona, Calif., at the age of 62.

At the request of Mr. Cleaver’s family, a spokesman for the Pomona Valley Hospital Center, Leslie Porras, declined to provide the cause of death or the reason Mr. Cleaver was in the hospital.

Source: New York Times obituary