BRITAIN’S INVOLVEMENT WITH NEW WORLD SLAVERY & THE TRANSATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE: BRITISH LIBRARY

With a focus on the 17th and 18th centuries, Abdul Mohamud and Robin Whitburn trace the history of Britain’s large-scale involvement in the enslavement of Africans and the transatlantic slave trade. Alongside this, Mohamud and Whitburn consider examples of resistance by enslaved people and communities, the work of abolitionists and the legacy of slavery.

The transatlantic slave trade was, in the words of the African American scholar and activist W E B Du Bois, ‘the most magnificent drama in the last thousand years of human history’.

For Dubois the drama was an unmitigated tragedy: ‘the transportation of ten million human beings out of the dark beauty of their mother continent into the new found El Dorado of the West. They descended into Hell’.

This trade relied on the commodification of African bodies, and would transform three continents in a period of enormous global change.

England’s early involvement with the Transatlantic Slave Trade, 1560–1690

The Atlantic world of the 16th century was dominated by the Catholic powers, Spain and Portugal. But in the territories of the western region of the African continent there were sophisticated polities that had been well established during Europe’s Middle Ages. These included the empire of Mali, with its renowned centre of learning and Islamic wisdom at Timbuktu. Throughout the 15th century Portuguese navigators explored the western coasts of Africa in the hope of finding a quicker sea route to Asia. In the process they established contact with the culturally and politically thriving kingdom of Benin in 1485. Eventually, in 1488, they navigated the southern tip of Africa. The Spanish, shortly after, sponsored an expedition led by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus. The aim was to find a quicker sea route to the East Indies by travelling west across the Atlantic. In 1492 Columbus’s crew sighted an island of the Caribbean and quickly went about exploring and bringing this ‘New World’ under their control. Vast riches then came through dismantling and exploiting the gold and silver-rich Aztec and Inca Empires.

The English had no chance of establishing a physical foothold in these lands at this time, but English privateers such as Sir Francis Drake preyed upon the treasure-laden Spanish galleons heading back to Europe. By the middle of the 16th century there was an increasing demand for cheap and unfree labour in the mines and on the plantations of Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the Americas. The Spanish in particular forced the indigenous peoples to work in exchange for ‘protection’. The system of forced labour used by the Spanish in the New World decimated the native population; overwork, cruelty and especially disease led to a catastrophic decline in their numbers. The Spanish and Portuguese authorities encouraged their traders to use Africans for this work instead. Sir John Hawkins, a cousin of Sir Francis Drake, on his first voyage to the Caribbean, stopped off near Sierra Leone in West Africa where his crew violently hijacked a Portuguese slave ship. They seized 300 enslaved Africans who were then sold on to plantation owners in the Caribbean. The English had made their first foray into the trade in kidnapped Africans; by 1715 they would come to dominate it.

When the English developed their own colonies in the early 17th century, they were also inclined to import enslaved Africans to do the hard labour on their plantations alongside poor English people who went there as indentured servants. The latter worked for a fixed amount of time to pay off the debt of their journey from England, whereas the enslaved Africans were the property, or chattel, of their owner for life. In the early years, most of these enslaved Africans were bought from Dutch traders.

After 1660, following the English Civil Wars and the brief republic under Oliver Cromwell, the reinstated monarchy started the large-scale involvement of the English in the slave trade. King Charles II and his brother James, Duke of York, helped establish a company that would control all English business in African slave trading. By 1672 it was called the Royal African Company (RAC) and its symbol was an elephant with a castle on its back. The ships of the Company enjoyed the protection of the Royal Navy, and the traders made good profits. Many of the enslaved Africans were branded with the initials ‘DY’, standing for Duke of York. They were shipped to Barbados and other Caribbean islands to work on the new sugar plantations, as well as further north to England’s American colonies. Between 1672 and 1713 the RAC transported some 100,000 enslaved Africans across the Atlantic.[1]

As soon as the Europeans began to exploit Africans as slaves, racist ideas emerged to justify what they were doing. Africans were now cast as negroes. Ideas about their racial inferiority were connected by some Europeans to the biblical story of Noah and the curse he placed on his son Ham, which passed on to all of his offspring. It was conveniently decided that the descendants of Ham were black Africans, while Noah’s other sons, the ancestors of the Semites and Europeans, were free.

At the same time, however, there were also writers who thought these ideas were nonsense. Thomas Browne wrote in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica (Enquiries into Vulgar and Common Errors) that he couldn’t see black people as cursed, since that was not their own perception and they were instead very happy with how they looked and lived:

Lastly, Whereas men affirm this colour was a Curse, I cannot make out the propriety of that name, it neither seeming so to them, nor reasonably unto us; for they take so much content therein, that they esteem deformity by other colours, describing the Devil, and terrible objects, White.

Slave societies in England’s Caribbean colonies, 1660–1780

The colonial settlements on Caribbean islands were quite distinct from the societies that had used slaves in previous centuries. By 1684 there were approximately 46,500 enslaved Africans, and 19,500 white Europeans on Barbados.[2] Slavery defined the way that Barbadian society functioned and divided it along the lines of race. It was not ‘a society with slaves’, like the Roman Empire or Anglo-Saxon England, but instead ‘a slave society’. Since bondage was the almost universal human condition in Barbados, harsh oppression constituted its rule of law. Enslaved Africans had no rights. In 1661 the planters passed the Barbados Slave Codes: racist laws that legalised slavery, described the Africans as ‘a dangerous kind of people’ and allowed the most violent punishments for even the slightest deviance or any offence they committed. The white indentured servants, in contrast, came under the protection of English law, but the new laws took any such rights away from enslaved Africans.

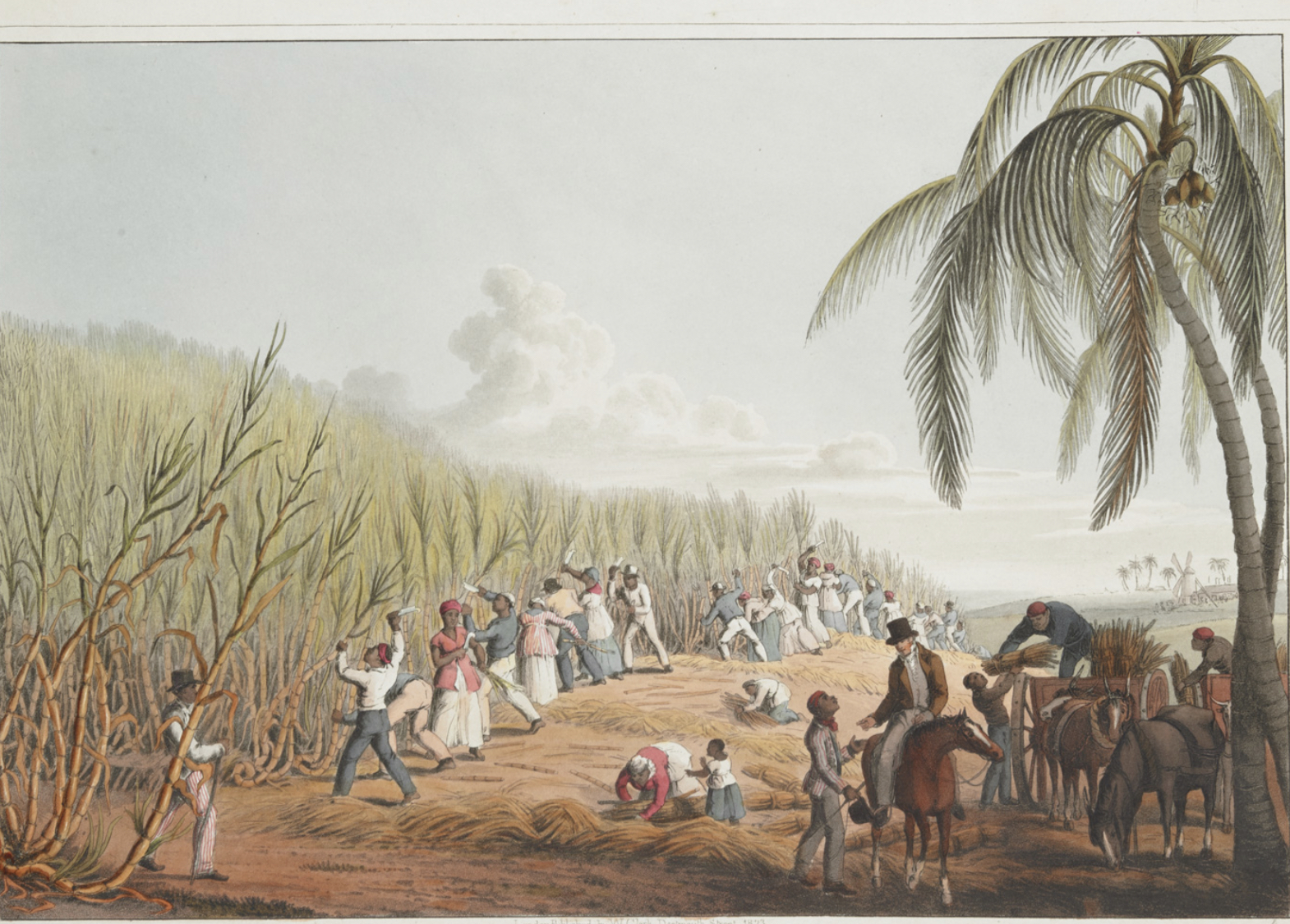

Sugar was established as a major cash crop on even the smallest of islands, such as Saint Kitts, Nevis and Antigua, and enslaved Africans were imported to work on all plantations. Jamaica became the largest of Britain’s Caribbean colonies when it was captured from the Spanish in 1655. The transition of colonial power gave an opportunity for many of the enslaved African-Jamaicans to escape to freedom in the mountainous regions of the islands. These successful runaways became known as Maroons and they fought off all attempts by the British to conquer them in the early 18th century. A treaty settlement confirmed Maroon autonomy, but in return the Maroons agreed to co-operate with the British in returning any new enslaved runaways from the plantations and curbing future revolts.

The slave trade was a major part of economic growth in Britain’s North American colonies. New England merchants were involved in the trade in West Indian sugar and rum, as well as contributing to the commerce of slavery in shipbuilding and other crafts. Slavery itself was widespread in the southern colonies, where plantations were established for the growth of tobacco, rice and indigo. Following the pattern of Barbados, the North American colonies introduced slave codes to control large numbers of enslaved African peoples in their societies. The colony of Georgia was the last of the original Thirteen Colonies to be established, led by General James Oglethorpe in 1732. Oglethorpe was opposed to slavery and insisted that only free labour would be used on Georgia’s farms. But as soon as he retired back to Britain, the plantation owners changed Georgia’s laws to allow them to own enslaved Africans, like their rich neighbours in the Carolinas.

Operating the British transatlantic slave trade, 1680–1807

Although notions of individual liberty were enshrined in the Bill of Rights of 1689, many of the same politicians and merchants that sought this liberty for themselves were eager to expand the transatlantic slave trade. By 1770 British traders were trafficking roughly 42,000 enslaved Africans across the Atlantic every year.[3]

The key ports for British companies trafficking Africans across the Atlantic were Bristol, Liverpool, Glasgow and London. The merchants, shipbuilders, metal manufacturers and sailors who directly furnished the slave trading expeditions were a major source of income and wealth for these port cities, and their economic activity would have had links with the prosperity of many thousands of people in support trades. The financial benefits of the trade extended to the stockholders of the Royal African Company, including the royal family. Indeed, when King James II lost the throne in the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89, he funded his exile in France by selling his stock in the RAC. Major fortunes were made by senior slave merchants.

Edward Colston was one such slave trade magnate from Bristol, and he funded a wide range of charitable projects with his legacy, including schools and almshouses for the poor of the city. The priest who preached at his funeral in October 1721 would not have recognised the irony when he said that Colston ‘knew of no want, but that of more vessels wherein to deposit the overflowings of charity and beneficence’.

This period witnessed what we would recognise as a globalised economic system. Tea, coffee, fine cloths and porcelain from Asia became highly desirable and common sights throughout England. Growing demand for these goods led to increased production that in turn led to lower prices. Coffee-houses sprang up in British cities, and the bitter drinks and confectionaries served there were sweetened with Caribbean sugar, which was becoming increasingly affordable. It is fair to say that by the late 18th century the British were a nation of sugar addicts.

The ships involved in the slave trade followed a triangular route between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Many historians have chosen to refer to transatlantic slaving by the shape that these routes cast on the map of the Atlantic. The first leg of this triangular journey was from one of the British ports to the west coast of Africa, where the ships would unload the manufactured goods produced in Britain in exchange for enslaved Africans. Slavers could spend weeks, even months in African ports, waiting to load up their ships with their new human cargo for the second leg of the journey across the Atlantic, known as the Middle Passage. Many of the greatest brutalities and degradations associated with the institution of slavery took place during the months the Africans spent on board. Ship captains maintained strict discipline, whipping and often murdering any captive Africans who did not co-operate. Many of the enslaved, held in unimaginable conditions below deck, fell ill with a range of diseases such as the ‘bloody flux’, a type of dysentery that spread rapidly through the cramped and unsanitary conditions of the slave ship.

Death rates varied but in general were extraordinarily high. Some captains congratulated themselves if only ten per cent of their human cargo perished. Casualty rates in the range of 20–30 per cent were not uncommon, especially in the first half of the 18th century.

Merchants were eager to protect themselves from the ‘perils of the sea’, and so paid insurance houses to cover them against damage to or loss of cargo. In 1781 the crew of the slave ship Zong, which was running low on supplies in the Atlantic, murdered, by throwing overboard, 133 of their captive Africans. The owners of the ship, who had taken out insurance on the lives of the slaves, tried to claim the insurance money, but they were challenged in court by the insurers. The case was given national prominence by Olaudah Equiano, an abolitionist and a freed slave, along with his friend, the anti-slavery campaigner Granville Sharp. Lord Chief Justice Mansfield ruled in favour of the insurers, while the Solicitor General, Justice John Lee, insisted it was a matter of property, that Africans were not human beings, and argued vigorously against bringing criminal charges against those responsible for the murders. Abolitionists continued to work tirelessly throughout Britain to bring the nation’s attention to the crimes associated with the institution of slavery. Their efforts were to be complemented by those of the enslaved Africans themselves who resisted their oppression.

Slave resistance in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, 1700–1833

Unsurprisingly, resistance to slavery was common. The most prominent form of resistance was collective rebellion, although it was usually the culmination of other forms of resistance. Slaves on plantations often tried to frustrate the plantation system by working slowly, pretending not to know how to perform certain tasks in order to avoid doing them and sabotaging machinery to obstruct production. The slave masters had a particular fear of arson. In 1740 slaves were suspected of setting a number of fires in Charleston, South Carolina that led to the destruction of over 300 houses. At the end of the century, a major slave revolt took place on the French Caribbean colony of Saint Domingue between 1791 and 1804. Initially led by Toussaint L’Ouverture, who was born into enslavement, the black population gained their liberty while fighting off the British and Spanish, and a major French attempt to re-enslave them. Eventually, remaining leaders declared Saint Domingue an independent black republic and renamed the island Haiti in 1804. C L R James describes the events as the ‘only successful slave revolt in history’, as no other revolt directly resulted in the creation of an independent black state, free from slavery. Closely connected to the revolutionary events in France at the time, this ‘Haitian Revolution’ was to be both inspirational for other enslaved people in the West Indies and frighteningly apocalyptic to other slaveholders, especially the British.

The insurrection occurred during decades of war between the British and the new regimes in France, so the defence of West Indian colonies became paramount. The British government established several West India regiments for this purpose, and became a major purchaser of enslaved Africans in the late 1700s and early 1800s to fill up the ranks of these forces. This was all done as secretly as possible to avoid a furore in the midst of the debates in Parliament about the abolition of the slave trade.

From the mid 18th century, Africans and people of African descent – some of whom were enslaved, or former slaves – wrote poems, letters, pamphlets and autobiographies which were published in Britain and America and reached wide audiences. Among others, the works of Phillis Wheatley, Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano contributed to the growing abolitionist movement.

The abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire was enacted by the Act of 1807, but the institution of slavery remained intact. Slave rebellions continued, and the final decisive one occurred on the island of Jamaica at Christmas 1831. It began as a peaceful general strike led by Samuel Sharpe, a Baptist deacon as well as an enslaved labourer, but when the planters responded with swift brutality, the slaves torched the cane fields and some escaped to the mountains to begin a brief campaign of guerrilla warfare. The British military garrison ruthlessly put down the rebellion, killing over 500 enslaved people altogether. This ‘Baptist War’ has been seen as one of the factors that clinched the emancipation of slaves throughout the British Empire in the Act of 1833.

But when enslavement ended, it was the plantation owners who received compensation for the loss of what they believed was their property. This compensation was not just financial: the planters had convinced Parliament that the enslaved had to be taught how to be free and that they needed to serve under their former masters as apprentices for four years before being granted full emancipation. The racism that made it possible to think of people as slave labour gave way to a racism that freed individual slaves while justifying the domination of entire nations. Eventually, like the sovereignty of the slave master, imperial dominion had to be relinquished as Britain’s colonies gained independence and joined the Commonwealth in the decades that followed the Second World War.

The scars of plantation slavery and colonialism never fully healed; ideas of white superiority proved remarkably durable, particularly within powerful institutions such as national police forces in Britain and the United States. This fact was acknowledged in Britain in 1999 following the Macpherson Report which recognised that institutional racism was a major factor in the violence, negligence and discrimination that had led to decades of tension between the children of Commonwealth migrants and police forces throughout England.

The pervasive legacy of British slave ownership, while uncovered through the work of historians, remains uncomfortable and largely ignored in most parts of public and political life.

Footnotes

[1] Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery (London: Verso, 1997), p. 255.

[2] Hilary Beckles, A History of Barbados (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 32.

[3] ‘Estimates’, The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database<http://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates> [accessed June 2018].

Written by Abdul Mohamud

Abdul Mohamud is a Senior Teaching Fellow at University College London – Institute of Education, tutoring trainee history teachers, and teaches history in an East London school.