‘The man who shot my mum is still living his life’: Cherry Groce’s son on life after police brutality

The Guardian, Simon Hattenstone, 5 September 2020

Lee Lawrence was 11 when armed officers broke into his bedroom and shot his mother, paralysing her from the chest down. Has he finally found something close to justice?

Lee Lawrence was seven when he decided he wanted to be a police officer. He adored cop shows: Starsky & Hutch, The Professionals, CHiPs – you name it, he watched it. Yes, there were the chases, thrills and spills, but it was more than that. “There was always that sense in me, as a kid, that I like fairness, I want to help people, to be the good guy.”

He was 11 when his life was turned on its head. The date, Saturday 28 September 1985, is etched in his mind. It was 7am and the family were in bed at home in Brixton, south London. Lawrence was sharing the downstairs bedroom with his mother Cherry, father Leo and older sister Sharon. (His sister Juliet, who was six months pregnant, was in her bedroom, while his younger sister Lisa and two children of a family friend were asleep in the living room.) Lawrence liked sharing; it made him feel secure. But suddenly there was an almighty crash. His mother jumped out of bed to see what was happening. The next thing Lawrence heard was a gunshot.

The bedroom door had been smashed down. Lawrence saw his mother on the floor and a man still pointing his revolver at her. She had been shot in the spine. “I heard her saying she could not feel her legs, she couldn’t breathe and she was going to die.” Lawrence screamed at the officer that he’d kill him if he touched his mother again. He says the officer then pointed his gun at him and said, “Somebody had better shut this fucking kid up.”

It gradually dawned on the family that the man with the gun was not an armed burglar but a police officer. The scene became hellish. Thirty armed men emerged from nowhere, yelling incoherently, dogs straining on their leashes. In a horrifically botched dawn raid, the police had been looking for Lawrence’s 21-year-old brother Michael, who had allegedly threatened officers with a sawn-off shotgun a few days earlier.

By the time the ambulance arrived, Lawrence had abandoned any thought of working for the police. His father followed his mother to hospital and the children were left with two police officers – colleagues of the man who had shot their mother. Lawrence’s world had imploded, and the shooting was also about to send shockwaves through London: rumours circulated that Lawrence’s mother had died and there was a two-day uprising in Brixton, with 10 police officers and dozens of civilians reported injured, and one dead.

***

Lee Lawrence, now 46, is a gentle, dignified man. He does not swear lightly, but when he thinks back to that day he can’t help himself. “Excuse my language, but the headfuck around that. I’d never experienced anything negatively with the police – and now I’m left in the house with these two officers, and you’re from the same team, or gang, that’s just done that to my mum. How have we been left with you? How can I trust you?”

Thirty-five years on, Lawrence has written a book about the impact that day had on his family. The Louder I Will Sing is a powerful, moving memoir – part rite of passage, part love letter to his mother, Dorothy “Cherry” Groce, and part instruction manual on how to fight for justice. The book takes its title from the Labi Siffre song Something Inside So Strong (“The more you refuse to hear my voice, the louder I will sing”). It took him three decades to gain justice for Groce, who was left paralysed below the chest – and it was a very different kind of justice from that which he had envisioned.

Groce, who was 37 when she was shot, was hospitalised for two years afterwards. The siblings were split between different carers: two sisters went on to have traumatic childhoods and often missed school. Lawrence, meanwhile, would visit his mother in hospital every day after school and stay with her until throwing-out time. School, hospital, sleep became his life.

When she left hospital, Groce was rehoused in a bungalow in nearby Gipsy Hill, with Lawrence, Sharon and Lisa. Leo had by then largely vanished from their lives, so Lawrence, barely 13, became the man of the house. Did they talk about what had happened? He shakes his head. “No. We never talked about it.”

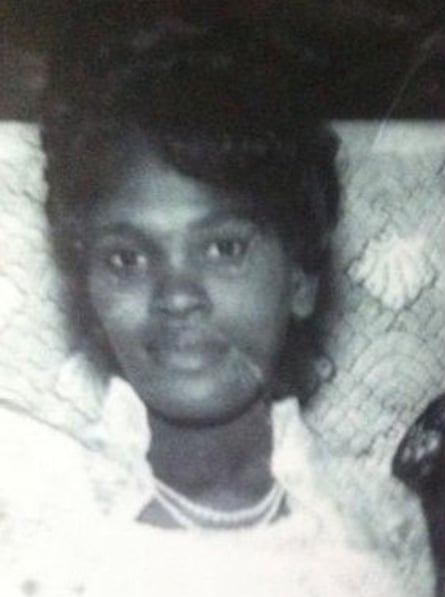

Groce in her early 20s.Photograph: courtesy of Lee Lawrence

Groce had been a strong, fun-loving free spirit. Her son’s book starts in 1982, with her returning home from Brixton market with a new single, Someone Loves You Honey, by June Lodge and Prince Mohammed. She puts it on the turntable and invites her children to dance. This is his abiding memory of her before the police raid: young, beautiful, a tiny ball (she was 4ft 10in) of dancing energy. She had worked as a secretary and a cleaner, and gone on to bring up her six children almost single-handed.

When she left hospital, Groce tried to carry on as if nothing had happened, cooking for the family and vacuuming from her wheelchair. But, in pain and unable to look after her children as she once had, she gradually withdrew, becoming reserved and occasionally sharp-tongued. Every day before school Lawrence would ask if she wanted a cup of tea. One day she lashed out and asked why he didn’t just make it, instead of always asking. She hated their role reversal and retreated to her bedroom and her books, reading up on African and Jamaican history. Groce had moved to England when she was 15 and was proud of her Maroon lineage: the Maroons had fought against the British, escaped slavery and established free communities in the mountains of Jamaica. But when she talked to her teenage son about this, he felt confused: “I used to be like, ‘Mum, it’s too deep for me.’”

He began to ask his own questions. Why had he been given no support after the shooting? “Two weeks later, I was back at school. No teacher ever said, ‘How d’you feel about what happened?’ No adult ever asked. So you’re bottling all this anger.” He had a recurring nightmare that he was shot and began to resent his father and brother Michael: “The two male figures I should have been able to look to for support had disappeared. I felt they had abandoned my mum.”

Mum said, ‘The police are a force and we can’t beat the force.’ I thought, I’m never going to accept that

Up until the shooting, Leo had visited at weekends, cooking mouthwatering goat curry and Jamaican stewed chicken, but he was not a reliable parent, often drunk and sometimes aggressive. He insisted the two children he had with Groce (Lawrence and Lisa) call him Leo rather than Dad. Lawrence was later reconciled with Leo, who died earlier this year. As for Michael, Lawrence regarded him as a “novelty” older brother, who would occasionally turn up and show him an exciting time. Michael is now a poet and community worker, but then he was in and out of jail. Lawrence was an old-fashioned boy: he believed it was a man’s responsibility to look after women, so if his father and older brother weren’t there for his mother, he would make sure he was.

In January 1987, 16 months after the shooting and having faced criminal charges, the officer who fired the shot, Inspector Douglas Lovelock, was acquitted at the Old Bailey of maliciously wounding Groce. To Lawrence’s astonishment and anger, his mother accepted the verdict. “I was so upset, I was shaking. Mum said, ‘Lee, the police are a force. And we can’t beat the force.’ I thought, I’m never going to accept that.” For a long time he imagined hunting down Lovelock and exacting vigilante revenge. Did he ever come close? “I wouldn’t say close. But I remember asking questions about how to find him.”

Lawrence was 13 or 14 when he next came into contact with the police. He was riding pillion on a friend’s moped, which turned out to be stolen. The arresting officer called him a monkey. He was so shocked, he burst out laughing. “I couldn’t believe it. I thought, ‘This only happens in movies.’ And that hardened me. It was like, so this is really how you see us?”

Groce with her brother Mervin in 1987, at the Old Bailey trial of the police officer who shot her.Photograph: courtesy of Lee Lawrence

As the teenage Lawrence became more politicised, he began to wonder why nobody seemed interested in his mother’s story. “In Black History Month, there would be programmes on telly about the 1981 uprisings, but when it came to 1985, and a woman shot in her home in front of her children, it was skimmed over. There was a little flame inside of me from that point.”

***

We are in the middle of an August heatwave when I meet Lawrence in London, but he manages to look smart even in denim shorts and a T-shirt. He tells me he could never ask his mother for new trainers because money was so tight, so he tried to steal them. He was a hopeless thief and got caught; the security guard looked at his worn trainers, took pity on him and let him off. But he was about to get better at outsmarting the authorities. After leaving school at 15, he decided the only way he could look after his mother and sisters was by selling drugs. “I saw myself as a businessman, and this was a means to an end. I would never refer to myself as a dealer.” He stresses he never sold to street addicts. “My clients were rich, traders. They spoke like they were part of the royal family.”

By 15, he had become known on the streets as Younger Cowboy, feeding off his older brother’s tough reputation. An earlier persona had been Rudy Lee, part bad boy, part rude boy, and in his 20s he was Brandy Lee, because of his love of the drink. Tell me about Brandy Lee, I say. He laughs: a bit proud, a bit sheepish. “OK, so Brandy Lee is charismatic, a smooth guy, a ladies man. A bit egotistical.” He was also a devoted son and a full-time carer for his mother.

I ask Lawrence how long he sold drugs for. “You want me to incriminate myself? Hehehe!” He has a big, exuberant laugh. He won’t give dates, but says he soon began to see the contradiction in his business plan: he was dealing drugs to provide stability for his family, all the while risking leaving them with nothing. By 21, he had a son, Brandon, and responsibilities, so he quit while he was ahead. He met his wife Gem when he was 28, had two daughters with her (Harmony, 12, and Ruby-Lee, eight) and settled down to a simpler life. By day he was his mother’s official carer; in the evenings he DJed, organised events and ran a nightclub. In the early 2000s, he began to work as a black-cab driver.

Lawrence with his mother and son Brandon, at his wedding in 2006.Photograph: courtesy of Lee Lawrence

As the years passed, Lawrence became determined to right the wrongs done to his mother. A week after Groce was shot, Cynthia Jarrett died of heart failure during a police search of her home in Tottenham, north London. Her death led to the Broadwater Farm riots and the killing of PC Keith Blakelock. (Winston Silcott, Mark Braithwaite and Engin Raghip were convicted of Blakelock’s murder in 1987; four years later, all three convictions were overturned when scientific tests showed Silcott’s confession had been fabricated.)

In 2010, Lawrence says, a friend went to a celebration of Jarrett’s life. “And he said to me, ‘How come your mum’s not recognised in that way?’” He told his mother he needed to do something to acknowledge her life and that his aunt, the actor Lorna Gayle, was thinking of dramatising her story. “She didn’t like the limelight, but I kept bugging her about it and eventually she said, ‘OK, if you want to do something, do something.’” But he never got the chance while she was alive: Cherry Groce died of kidney failure in 2011, aged 63.

By then, Lawrence was no longer interested in retributive justice. He helped put on Gayle’s play, Her Story, at the Brixton Ritzy. In 2012, he decided a blue plaque should be put on the family home, still owned by Lambeth council, to celebrate his mother’s life. When the council refused, he went ahead anyway.

After Groce’s death, the pathologist’s report established a link between the shooting and the kidney failure that led to her death, triggering an inquest. But the family could not afford a lawyer and were refused legal aid. Lawrence approached his local MP, Chuka Umunna, for support, and started a petition. By the time he handed it in to 10 Downing Street in April 2014, there were 130,000 signatures. The family were granted legal aid. “For the first time, I started to see people who didn’t necessarily look like us supporting us. I thought, ‘Look what we can achieve when we come together,’” Lawrence says.

Shortly before the 2014 inquest, he discovered West Yorkshire police had investigated the shooting as an outside force, but the subsequent report had been buried. The family won a fight for disclosure and the findings of the 357-page report were damning. Assistant chief constable John Domaille had catalogued error after error, concluding: “The raid should not have gone ahead in the manner planned due to the total lack of information… grave risks were created both for public and police, which should have been avoided.” The Metropolitan police accepted all of Domaille’s findings.

I wanted accountability for how my life and my sisters’ lives were ruined because of police failures

On 10 July 2014, 29 years after she had been shot, the inquest jury at Southwark coroner’s court found that “Dorothy Groce was shot by police during a planned, forced entry raid at her home, and her subsequent death was contributed to by failures in the planning and implementation of the raid.” The jury found there were failures to properly brief officers that Michael was no longer wanted by police; to adequately check who lived at the property; and to carry out adequate observations on the house.

Lawrence was vindicated. “That acknowledgment was the greatest gift I could give to Mum in her absence,” he says now. A major review of Met gun policy after the shooting had already led to a ban on detectives carrying firearms, and Groce had received £500,000 compensation in an out-of-court settlement in 1993, too late to stop Lawrence selling drugs, and too little to support her until she died. But the police had never formally apologised. Now, after the inquest, Met commissioner Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe did, admitting the police had caused “irreparable damage”.

Lawrence told the police an apology wasn’t enough.

“My life and my sisters’ lives were ruined because of what happened that day. I wanted accountability for how our lives were altered because of their failures,” he says.

When the Met refused to accept liability, the family returned to court. In 2016, the high court ruled that the Met had a duty of care to five of Groce’s six children (excluding Michael because he wasn’t in the house at the time, but including their sister Rose who had returned home straight after the shooting) and would have to pay them compensation.

There was also the matter of justice, Lawrence says. “The man who shot my mum is still living his life. No one went to prison. No one was penalised.” His lawyers, Bhatt Murphy, suggested the family could receive “restorative justice”, meeting the Met to explain the impact the shooting had had and finding ways for the Met to make amends. As part of that process, the Met agreed to the family’s request to have a role in police training; for a programme to be developed to support people who had been traumatised as a result of wrongful police actions; and to make a contribution to the work of the Cherry Groce Foundation, established in 2014 to support people in the community with mobility issues. Lawrence says the Met is yet to fully deliver on its promises.

Since then Lawrence has worked as a voluntary consultant for the police – sitting on boards, going to passing out ceremonies at the Met’s Hendon police college and completed a training session on the police complaints process. He is not impressed by what he’s seen: “This is a system that is broken.” Nor is he convinced the will is there to fix it. The Met is still overwhelmingly white (while the London population is 59.8% white, its police force is 85% white) and is four times more likely to use force against black people. Lawrence says he asked one graduating officer if they were taught negotiation skills and the officer said no: they were taught to make assumptions and work on the basis of those. Lawrence immediately thought of the assumptions he believed Lovelock had made all those years ago when he raided their home. “The danger is your assumptions are going to be based on your life experiences. How do you see that person? Are they always the criminal in your mind?”

He sits on the Met’s professional standards board, and is beginning to wonder why. “You’re just there to give a view. But they don’t have to take your view on board. You don’t see outcomes.”

In recent months, his frustrations have intensified. The fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor this March, after police forcibly entered her flat in Louisville, US, brought back terrible memories, as did the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Like Groce, Floyd had told the police he couldn’t breathe.

Every day seems to bring a new story about reckless stop and searches of black people in Britain. In June, 24-year-old Jordan Walker-Brown was stopped by police. He ran away because, he said, he was carrying a small amount of cannabis. When the police Tasered him, he fell off a wall and was left paralysed from the chest down, just as Groce had been.

A few years ago, Lawrence was stopped by the police after a cyclist rode into the back of his car at 10am one day. The cyclist had apologised, but the police still aggressively breathalysed Lawrence.

“A white lady came over and said, ‘I’m not moving, I’m a witness.’ The officer said, ‘What for?’ She goes, ‘I see this every day. All you do is stop young black men and harass them.’ That incident showed me there’s still a lot to do.”

Would he walk away from working with the police at any point? He smiles. “Of course. I’m very close to it now. I’m not seeing enough change. I’ve got to worry about my own credibility, right?”

If he did walk away, he would have plenty to occupy him. After his mother’s death, he started Mobility Taxis, a specialist firm for disabled people. Originally a one-man band, it quickly expanded, though it has suffered in the pandemic, with many customers shielding.

Wherever Lawrence looks now, there are welcome reminders of his mother. A pavilion is being built to remember her in Brixton’s Windrush Square, designed by architect Sir David Adjaye. “It’s inspired by the mountains of Jamaica and West Africa,” Lawrence explains, “with Mum connecting the two. It’s a place of reflection and shelter.” Meanwhile, the Cherry Groce Foundation is creating a programme of teaching resources for schools across the country, to tell her story. The Met has agreed to sponsor a prize in her name, to be awarded to an officer who has done outstanding work in the community. As well as the book, a film about her life is planned.

Of course, none of this can make up for what happened, Lawrence says. “But if I can say, ‘Look at the positives that have happened as a result’, I can live with it.” For decades, he despaired at the fact that he had no control over his mother’s narrative. Now he hopes that is about to change. “To most people, my mum is just the woman who was shot by the police. And that’s it. Full stop. For me, she’s so much more.”

• The Louder I Will Sing by Lee Lawrence is published by Sphere, an imprint of Little, Brown Book Group, on 17 September at £16.99. To order a copy for £14.78, go to guardianbookshop.com.