The Problem Of Watching World News Through White Eyes Only

By Marcus Ryder, Visiting professor, Sir Lenny Henry Centre for Media Diversity 26 Aug 2020

Marcus Ryder looks at the lack of diversity within the reporting of world news. Credit: Unsplash

Only about 0.2% of British journalists are black, compared to 3% of our country’s population. When it comes to the ethnic backgrounds of UK foreign correspondents, figures are scant – but the picture appears to be even less diverse. Marcus Ryder examines why looking at world news through only white people’s eyes is a problem for all of us.

I officially left the BBC and moved to China just over four years ago.

Knowing I was going to Beijing, a good friend and reporter at Channel 4 News introduced me to Danny Vincent – a freelance journalist also working out of the Chinese capital for Channel 4.

Meeting Danny was an absolute godsend as he showed me the ropes and how to navigate a new, large and often perplexing city. Danny now works for the BBC and has moved to Hong Kong.

One of the things that makes him unique is he is one of the only black journalists working for a foreign news media organisation in China.

Not only that, the sad truth is he is one of the few black journalists (outside of Africa) working as a foreign correspondent for any European, North American or Australian news organisation anywhere in the world. Official statistics on the ethnic backgrounds of UK foreign correspondents do not exist (as far as I can find).

The result of this is people in the UK, and what is frequently termed “the West”, literally see the world through the eyes of white people. What is deemed important, the values that are attached to events, and how the world is interpreted is all mediated through a very narrow set of people.

This first struck me in China when I was talking to foreign journalists. In recent years the issue of the treatment of the Uighur ethnic group in Xinjiang province has received some media attention, but the universal message I heard was that China is “not like other countries” because it is almost racially homogenous.

No one would have dreamed of saying the UK was ethnically homogenous during the 1990s

Marcus Ryder

As a black man I found the notion that a country the size of China with a population of almost 1.4 billion people being “racially homogenous” strange to say the least. A little bit of research and you quickly find out that China officially has 56 ethnic groups: Achang, Bai, Bonan, Bouyei, Blang, Dai, Daur, Deang, Dong, Dongxiang, Dulong, Ewenki, Gaoshan, Gelao, Han, Hani, Hezhe, Hui, Jing, Jingpo, Jinuo, Kazak, Kirgiz, Korean, Lahu, Li, Lisu, Luoba, Manchu, Maonan, Menba, Miao, Mongolian, Mulao, Naxi, Nu, Oroqen, Ozbek, Pumi, Qiang, Russian, Salar, She, Shui, Tajik, Tatar, Tibetan, Tu, Tujia, Uighur, Wa, Xibe, Yao, Yi, Yugur, Zhuang.

Han are by far the largest at around 92%, but this is smaller than the percentage of the UK’s population who classified themselves as white according to the 1991 census (94%), and no one would have dreamed of saying the UK was ethnically homogenous during the 1990s. About 86% of the UK population now identifies as white, according to the most recent 2011 census.

In my view, the simple reason foreign journalists can all too easily make this mistake is because they are often from the majority culture back home, and the Chinese people they are interacting with are also largely from the majority Han group. It literally gives them a skewed perspective of the country they are reporting on and how the rest of the world views the country.

It is no coincidence that, as one of the only black journalists working for a major foreign news organisation in China, Danny Vincent led the world in reporting on the xenophobia Africans suffered during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is always hard to attribute direct causality but, following his reports, both China and a variety of African governments entered talks to resolve the situation.

Racial diversity does not only alter your perspective on race, it can also alter your entire perspective on how you view the world.

For example, I know as a black man who has been unfairly stopped and searched by police in the UK (a common occurrence unfortunately for most British black men) I have a different perspective and relationship with police in general than the majority of white journalists I meet. This means we may cover stories differently or weigh the authority of different news sources quite differently.

This does not just apply for the police but is also true with regards to reporting on health issues, education, and politics, to name just three examples.

My background shapes my reporting whether that is in the UK or in another country.

The lack of diversity among foreign correspondents also means we are missing important stories. By definition it is impossible to quantify the number of stories that are not being reported on. It is impossible to prove a negative.

But the example of Danny Vincent suggests that there are many stories being missed due to the lack of black foreign correspondents. The world was lucky that Danny happened to be based in China at the time and, as a black journalist, had access to some of the Africans suffering the alleged abuse.

All of this has serious human rights implications. How we report on ethnic diversity, police abuse, discrimination and certain sections of society being denied their human rights will all be filtered through who is doing the reporting.

The longer I have lived outside of the UK in Asia, the more I’ve realised just how skewed foreign reporting is due to the lack of diversity among foreign journalists.

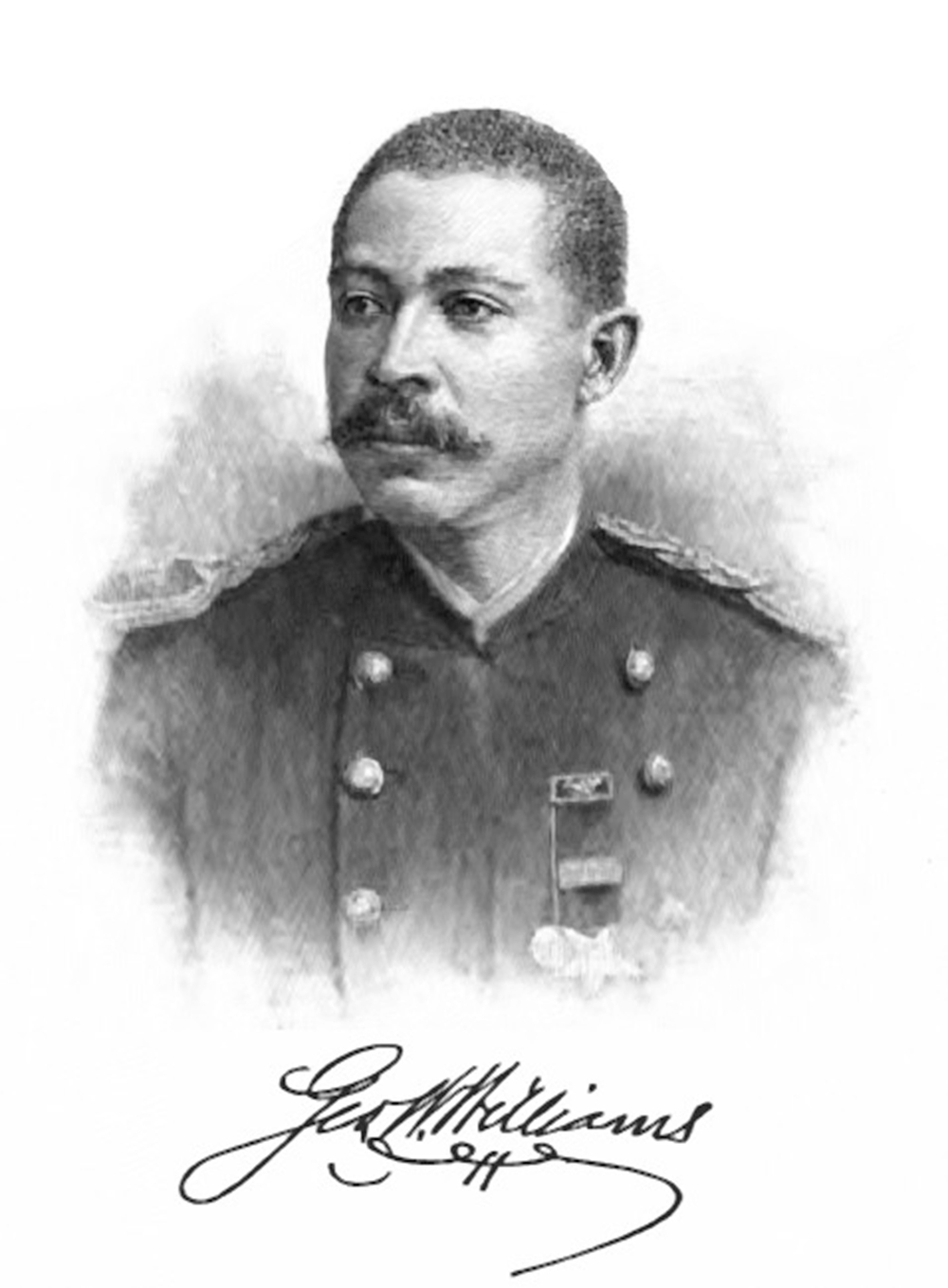

Black journalists have a long history of exposing international injustice which we must take inspiration from and never forget. We only have to look at George Washington Williams – the African-American soldier, politician, historian and journalist – who died in Blackpool in 1891 aged 41.

In the 19th Century, he documented and exposed the campaign of mutilation and brutalisation that Belgium’s imperialist King Leopold II waged against Congolese workers under the false pretence of a supposedly progressive “Congo Free State”. It led to an international scandal, with the Belgian government seizing control of the Congo Free State from its bloodthirsty monarch under the proviso of improving conditions.

If we want an accurate representation of the world, greater diversity among those bearing witness to it is essential.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of EachOther.