‘I’ve had to fight’: Kehinde Andrews on life as the first UK professor of Black Studies

From a childhood identity crisis to navigating academia, he discusses the importance of Black radical tradition – and why TV quarrels with Nigel Farage are worthwhile

Nesrine Malik Thu 4 Feb 2021 10.00 GMT THE GUARDIAN

When Kehinde Andrews was at school, his friends would never have imagined him growing up to become the UK’s first Black studies professor – nor that he would help found the first Black studies programme in Europe, at Birmingham City University. True, he grew up in the city, the son of two committed Black activists, who established numerous organisations and promoted the Black anti-racist intellectual tradition – but Andrews, 37, didn’t always embrace their legacy. In fact, his path to Black studies took a detour when he rebelled against everything it stood for.

“I had an identity crisis in high school,” he says. “I look back and cringe.” If this sounds like the usual chafing against parental authority, it was. But there was also a deeper – and sadder – reason. As the result of a sort of British version of bussing, Andrews travelled every day to a school with a good reputation in a predominantly white area. Even as a child, he says, he could see that Black students were pigeonholed. “The racial stereotypes were so clear,” he says. “It was so obvious, from day one, that Black kids don’t do well.” There was, he says, “a very clear path” based on what race the students were. “There’s me and one, maybe two, other Black kids in the top set – everybody else was in the bottom set. In my 11-year-old head, it was: ‘Well, I’m going to do well in school, so I’m going to go with the white kids.’ That was how it was set up.”

For Andrews, this meant not just ignoring the values and culture he had been brought up with (“I rejected it all. It was horrible”), but “falling into whiteness” – emulating the behaviour and interests of his white friends. He would go to the pub to watch England play and sing “patriotic, anti-Irish chants”. He “fell so far down the rabbit hole” that he began to listen to country music, he says, in his desire to be someone else. “Garth Brooks, if I remember correctly. It seems sort of trivial, but it really wasn’t.”

At his lowest point, this desire to be white culminated in him hating his hair. “I started not combing it and wishing it was straight and easy to manage, like my white friends’,” he says. “I got called a Bounty bar. And, looking back honestly, that was me.”

Today, he doesn’t judge his younger self or those he was trying so hard to copy. “We tend to think of people who embrace the negative stereotypes of blackness” – such as gangster culture – “as completely different to the ‘Bounty bars’. But they’re both saying blackness is important, blackness is my identity,” he says. Both, in other words, believe that blackness determines their path in life, whether they are running from that fact or trying to embrace it.

Eventually, he found his way back to the Black radical tradition in which he had been raised. Andrews’ mother was half white English, half Jamaican, a university graduate who was born in Britain. His father, from rural Jamaica, came to the UK in his early teens and left school without qualifications after his experience in the underfunded school system, which seemingly had no interest in the career prospects of Black boys. Their marriage represents to Andrews the union of “civil rights and Black power”.

His formative memories are almost all references to nurseries, Saturday schools, bookshops and local organisations that his parents – particularly his father – started. Andrews’ father was a founding member of the Harambee Organisation of Black Unity – which ran a hostel, the Marcus Garvey nursery, and the Harriet Tubman bookshop. His mother worked for the race relations board, which, as part of the government, was eyed with suspicion by some Black activist groups. His father, jokes Andrews, “thought my mother was a spy when they first met. I don’t know what happened, but she ended up giving him three children,” he says.

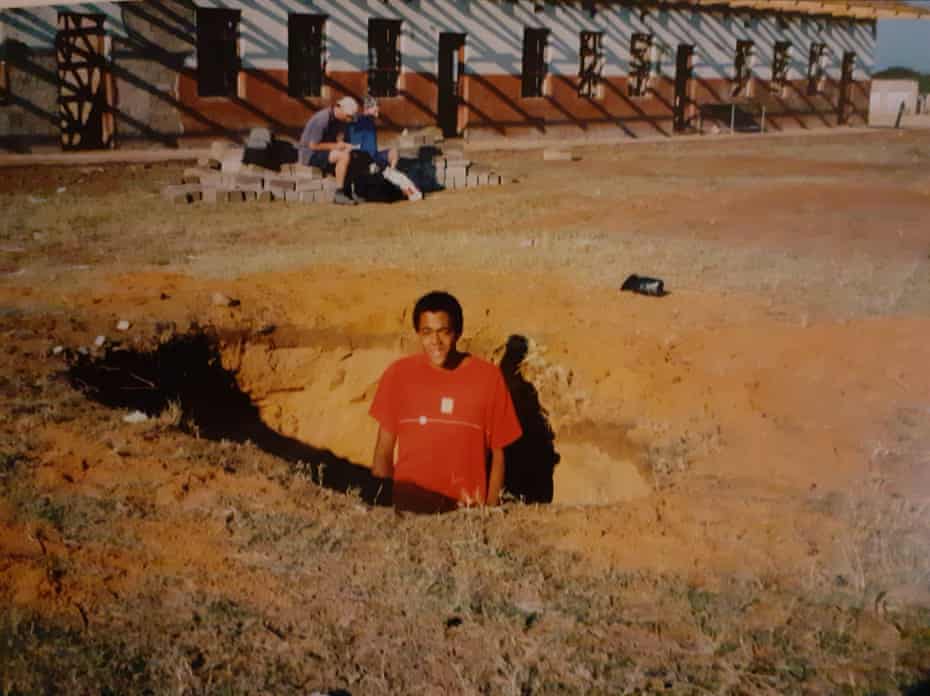

With parents so focused on improving education, maybe it was inevitable that he would return to their values through reading. “I started picking up the books lying around in my house,” he says, gesturing to a wall of Black literature behind him. It was, he says, quoting Malcolm X’s description of starting to read in prison, “like snow falling off a roof”. Travel swept off any remaining snow. A Voluntary Services Overseas youth exchange took him to post-apartheid South Africa, where he realised, despite legal changes, that an informal system still oppressed Black people. “Combined with the reading, coming back, I was a completely different person.”

By the time he was ready to reclaim this heritage, he realised a mass erasure of Black British history was under way. The markers of his childhood were disappearing. “The biggest contribution of Black families is in education, bookshops, Saturday schools. It’s almost completely gone: the Saturday schools are gone; the bookshops are almost all closed.” Saturday schools were set up in the 70s to counteract the historical neglect of Black children in state schools, but also to improve self-esteem by teaching Black studies. Andrews believes the disappearance of this supplemental infrastructure has had serious consequences, undermining the political education of the current generation of working-class brown and Black people.

He believes this is because a pivot to trying to change existing institutions – rather than nurturing separate organisations – has made it hard to foster the sort of communitarian spirit in which his parents thrived. “The biggest mistake we make in Britain is that we really do try to integrate into society.” Since the 80s, he says, there has been a gold rush for jobs and education in mainstream organisations: “I work as a university professor; I’m part of that moment.” But he says that means “we’ve neglected the alternative spaces – and then we wonder why everything’s gone wrong”.

The absence of those spaces has led to unrealistic expectations and demands of equality from institutions that are fundamentally opposed to change, he says – for instance, that the white-dominated media will support racial justice movements such as Black Lives Matter when historically they have often been hostile to or suspicious of Black political expression.

In the past, Black communities countered this by setting up their own newspapers. “There were so many community newspapers in the 70s and 80s,” he says. They no longer exist “because we have relied on the schools to change and the media to change. Our failure as a community is that we haven’t protected the legacy of our own.”

The theme of a fractured Black solidarity is central to his new book, The New Age of Empire. “Black consciousness is something we have never really achieved,” he says. Instead, he argues, individualism and self-interest have allowed exploitative forces – from white slave traders in west Africa to Chinese corporations – to co-opt local Black elites and enablers to do their dirty work and profit from it.

His Black studies course is an attempt to create such a consciousness, but he is circumspect in his hopes. “It’s an experiment.” Despite his pioneering position in academia (he calls it collectively “the university”), he seems sceptical – scornful, even – that it is a place from which to struggle for racial justice.

“I would never endorse a university as a place to do any of these things,” he says. “The metaphor I use a lot of the time is that we’re trying to colonise the university.” He says universities are fundamentally conservative spaces that need to be dragged into handing their rich resources – their buildings and funding – to Black studies. It is a high-friction process. “The university ain’t gonna change,” he says. “I’ve spent two decades in universities; they’re not changing.”

Instead, he sees this “experiment” as taking the radical Black education that he grew up with – a heritage that is not academic, but nevertheless intellectual – and incorporating it into the university, to pull levers outside the “bubble”. In the second year of his course, students have to apply their knowledge via a placement, usually within an organisation that works in Black communities. Grassroots and mainstream ones – such as state schools – qualify. He believes the course is the resurrection of an existing legacy, not the creation of a new one: “Black studies is new in the university; it’s not new in the United Kingdom.”

I’ve spent two decades in universities; they’re not changing

He blames himself and his peers for not raising awareness of Black history and activism in the UK. “I came up at a time when I had access to all this stuff. So, one of the things that we’re trying to do quite heavily is bring back this education.” Andrews has revived the Harambee Organisation and is opening the Garvey Education Centre on the site where the Marcus Garvey nursery stood five decades ago. He has also helped launch the website Make It Plain – a Garvey quote, naturally – “as a space to get Black radical thought out in our words”.

His academic position offers him the profile to do the work he needs to do. He leverages this as often as he can – sometimes in what can look like unsavoury, bear-baiting public arguments. Among other topics, Andrews has debated with Nigel Farage whether the English flag is racist and whether portraits of the Queen are offensive. He has also been in several spats with Piers Morgan, including one around the legacy of Winston Churchill.

Why does he do it? His justification is pragmatic. “People say to me: it’s demeaning. But the reason I keep doing it is, randomly, I would walk down the street and a Black person would come up to me and say: ‘Go on, Prof!’ The mainstream discourse is Good Morning Britain. I’m not trying to convince white people; that’s not what they want. They want spectacle and I’m a good spectacle.”

Black people, he believes, are relieved to have a representative in these debates – and to be given facts and tools with which to argue their points when these debates come up in their own lives. In other words, he gets to talk about ideas such as “the psychosis of whiteness” for clickbait, but this generates another conversation on social media, and in people’s social and professional circles, that is useful. You could say it is his version of “colonising the media”.

Andrews speaks with passion, but also exasperation at the false promise of change in a world that he believes is structurally hostile to Black emancipation. Changes that come after moments of raising awareness, such as Black Lives Matter, are too often hollow diversity, he believes. They may make “the number of Black people in an institution rise”, but do nothing to make those organisations operate in a more equal way. “People ask me all the time: is it terrible that I’m one of just 140 Black professors in the UK? Certainly. But if there were 600 Black professors, would it change anything? No.” Real change, he believes, cannot come from elite, conservative white spaces, no matter how well populated with Black people, because such spaces are fundamentally antagonistic to change.

This also means that, no matter how high you climb, little changes. “You get into these places and it’s terrible. I’m a Black professor. Great. I’m still Black. The last three years of my career, outwardly, have been amazing. Internally, it’s been the worst three years of my life. Universities are some of the whitest institutions that exist and, the further up the hierarchy you go, the worse it gets.” He describes constant battles with management to effect change.

Yet he stresses that it is not just individuals or managers who are to blame. “The nature of these spaces means they can change us, creating toxic environments of competition that leads to the classic ‘barrel of crabs’ scenario, where we are struggling over each other to get to the top.”

His breath quickens. “The battles, the scars. I’ve just had to fight. I’m always fighting. I’ve probably done permanent damage to my mental and physical health establishing this Black studies course. Honestly, since launching the degree, learning to navigate through extreme levels of stress and bouts of depression has become part of the job description.” He believes it is not sustainable or, in the long run, useful. “I would think of it as a failure if, in the next five years, I haven’t left the university,” he says. “In five years, if you find me still here, tell me I’ve sold out.”

He wants to focus his energy on the grassroots, providing “an account of society from a Black radical perspective” – and to include his four children in his work. The first “celebrity” they could name was Malcom X; he takes them to his talks as often as possible and is working with them on a “Choose Your Liberation” children’s book, a choose-your-own-adventure story that explains Black politics. He laughs, remembering himself at that age. “I need to be careful that they don’t rebel against their father and end up joining the Tories!”

The New Age of Empire by Kehinde Andrews is published on 4 February (Allen Lane, £20). To order a copy, go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply