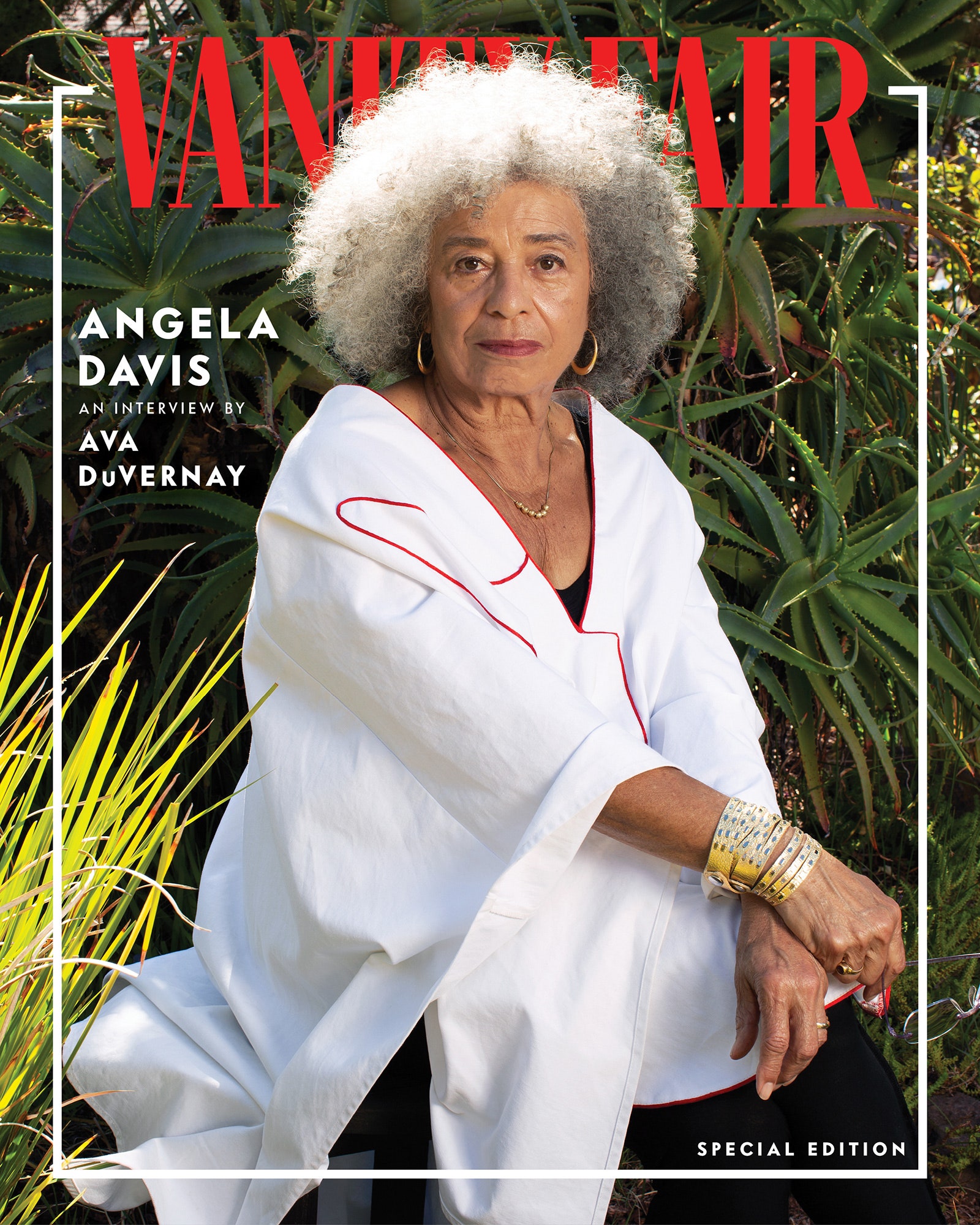

ANGELA DAVIS

Summary

Angela Davis was born on 26 January, 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama, USA, where she attended elementary and middle school. Her mother Sallye Bell Davis worked for the Southern Negro Youth Congress, which had ties to the Communist Party.

Education

She attended the Elisabeth Irwin High School, a progressive high school in New York City. Later she received a scholarship to Brandeis University, where she studied one year in France and graduated with honors and a degree in French in 1965. She continued her education at the University of Frankfurt in Germany, where she studied philosophy, and the University of California-San Diego, where she earned a Master’s degree. She went on to earn a Ph.D. at Humboldt University in Germany.

Career

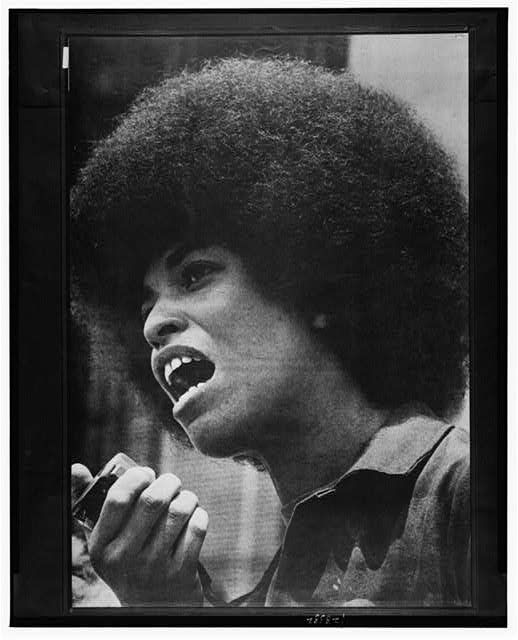

In 1969 she was hired to teach philosophy at the University of California-Los Angeles. The University of California Board of Regents, at the direction of Governor Ronald Reagan, who would go on to become President of the USA, dismissed Davis because she belonged to the Communist Party. Although a court ruling blocked the firing, the Board fired her again in 1970, this time for using “inflammatory language.”

Governor Reagan declared that Davis would never teach in the University of California system again. Davis’s vocal support for the Black Panther Party was another reason for her persecution by Governor Reagan and the FBI.

Trial

Angela Davis is well known for a notable arrest and trial in 1970. In January 1970 George Jackson, an inmate at Soledad Prison in California, and two other prisoners were charged with killing a prison guard. During the trial, Jackson’s 17-year old brother Jonathan Jackson took over a Marin County courtroom where he armed the black defendants and took the judge, prosecutor, and three female jurors hostage. By the end of the whole ordeal, the judge, Jonathan Jackson, and the armed defendants were killed while the prosecutor and one of the jurors were injured.

Angela was accused of purchasing the guns used in commission of the crimes so she was charged with “aggravated kidnapping and first degree murder.”

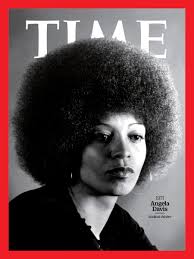

For decades, she was an active member of the Communist Party and the Black Panther Party, which the FBI sought to disrupt under its counterintelligence program. J. Edgar Hoover once said

the Black Panther Party “represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.”

J. Edgar Hoover, FBI Head

In the 1970s, Davis was a fugitive on the FBI’s most-wanted list. Once caught, she faced the death penalty in California but was later acquitted on all charges.

Angela went on the run. Four days after the initial warrant was issued, J. Edgar Hoover listed Angela Davis on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitive List. She successfully evaded arrest for two months before being apprehended in New York City. Thousands of activists around the world organized in her defense and demanded her release. After being incarcerated for sixteen months, Davis was tried and on June 4, 1972 she was found not guilty by an all-white jury.

Post trial

After her trial, Angela visited various Communist nations, including Cuba, the USSR, and East Germany. Upon returning to the United States, she resumed her teaching career, holding positions at several universities and colleges in California, including the Claremont Colleges, San Francisco State University, and the University of California-Santa Cruz, where she taught from 1991 to 2008. In addition to her teaching career, she has written a dozen books and has continued to lead the fight against racism, patriarchal oppression, war, incarceration, and the death penalty. Davis left the Communist Party in 1991 and established the Committees for Correspondence of Democracy and Socialism. In the early 1980s she was married to photographer Hilton Braithwaite. In 1998 she talked about her lesbian identity in an article in OUT magazine.

Through her activism and scholarship over the last decades, Angela Davis has been deeply involved in the US quest for social justice. Her work as an educator – both at the university level and in the larger public sphere – has always emphasized the importance of building communities of struggle for economic, racial, and gender justice.

Academia and writing

Professor Davis’ teaching career has taken her to a number of universities throughout the USA; San Francisco State University, Mills College, and UC Berkeley. She also has taught at UCLA, Vassar, the Claremont Colleges, and Stanford University. She spent the last fifteen years at the University of California, Santa Cruz where she is now Distinguished Professor Emerita of History of Consciousness, an interdisciplinary Ph.D program, and of Feminist Studies.

Angela Davis is the author of nine books and has lectured throughout the United States as well as in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America. In recent years a persistent theme of her work has been the range of social problems associated with incarceration and the generalized criminalization of those communities that are most affected by poverty and racial discrimination. She draws upon her own experiences in the early seventies as a person who spent eighteen months in jail and on trial, after being placed on the FBI’s “Ten Most Wanted List.” Davis has also conducted extensive research on numerous issues related to race, gender and imprisonment. Her most recent book is Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement.

Davis is a founding member Critical Resistance, a national organization dedicated to the dismantling of the prison industrial complex. Internationally, she is affiliated with Sisters Inside, an abolitionist organization based in Queensland, Australia that works in solidarity with women in prison.

Like many other educators, Professor Davis is especially concerned with the general tendency to devote more resources and attention to the prison system than to educational institutions. Having helped to popularize the notion of a “prison industrial complex,” she now urges her audiences to think seriously about the future possibility of a world without prisons and to help forge a 21st century abolitionist movement.

After the murder of George Floyd

Black Americans have always organized, she says: From Black women teaching children and adults to read at Sunday schools during the era of slavery, to the rise of the NAACP and the Urban League, to the work of activists such as sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois and journalist Ida B. Wells.

“For hundreds of years, Black people have passed down this collective yearning for freedom from one generation to the next,” she says. “We are doing now what should have been done in the aftermath of slavery.”

Before eliminating racism, she believes we must eradicate racial capitalism — a term designed to “encourage people to think about the ways in which capitalism and racism are interlinked.”

“There is no capitalism without racism”

Police departments and prison systems are “the most dramatic expression of structural racism,”. Demands to defund the police provoke a wide array of conversations, she says. The Minneapolis City Council’s move toward reforming its police department demonstrates the city’s commitment to creating “truly safe communities that represent the kinds of relations among human beings we would like to see,” she says.

“Sometimes it’s important to say what you mean and have the conversations,” she says. “And of course, when many of us began to talk about abolishing these institutions back in the 1970s, we were treated as if we were absolutely out of our minds.” When people demand to defund the police, some people tend to focus on the possible negative consequences of eliminating the institution of law enforcement instead of trying to “reimagine the meaning of public safety,” she says. “Now we can think about funding agencies and individuals and organizations that will help address issues of health — physical health, mental health,” she says. “This is the opportunity for us to begin to reimagine the meaning of these states.”

During the ‘60s and ‘70s, Davis saw several Black activists die, many at the hands of police. Today, several Black activists who were active during and after the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, have died. Many more have chronicled bouts with depression. Today’s young activists know the importance of addressing depression and trauma within organizations and movements, she says. “I think that bringing people together in movements, creating solidarity [means] representing ourselves not primarily as individuals,” she says, “but as members of communities of struggle.”

After almost half a century fighting for racial justice, a sense of hope keeps Angela going. Everyone needs to adopt an attitude of optimism — the same spirit shared by the many formerly enslaved Black people who believed in the possibility of freedom 200 to 300 years ago, she says. Seeing change enacted within weeks around issues she has focused on for years feels “bizarre” and “surreal,” she says.

Without people already doing work on the ground, she says the response to the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Tony McDade and Rayshard Brooks would not have reached the same level of outrage.

“Activists who are truly committed to changing the world should recognize that the work that we often do that receives no public recognition can eventually matter,” she says.This work is especially important with a president who “is totally ignorant of U.S. history,” Angela says. President Trump rescheduled a rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma — the site of one of the worst acts of racist violence against Black people in American history — from Juneteenth — the June 19 celebration of the end of slavery in Texas — to the following day.

Americans need to vote to help activists continue anti-racist work that “will allow us to envision the possibility of a society that is free of racism and sexism and homophobia and transphobia,” she says. The next election should focus on creating a framework to allow people calling for the abolition of modern prisons to “begin the hard work of creating new institutions,” she says. People with a progressive view of history who want to work to eradicate racism in the U.S. are becoming the majority, she says. For Angela, this shift signifies years of hard work materialising.

“I am just so happy that I have lived long enough to witness this moment,” she says. “And I think that I see myself as witnessing this moment for all of those who lost their lives in the struggle over the decades.”

Sources: Archives.gov; npr.org; speakoutnow.org