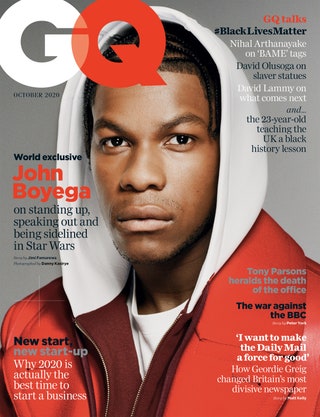

John Boyega: ‘I’m the only cast member whose experience of Star Wars was based on their race’

By Jimi Famurewa, 2 September 2020, GQ Magazine (UK)

During Britain’s Black Lives Matter rallies in June, John Boyega wrote his name in the history of racial justice. And here, in his first interview since finishing Star Wars and that unguarded address from a Hyde Park stage, he explains how both platforms inspired him to make a stand, but for very different reasons. Now, starring in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe as a Met policeman in the depths of institutional racism and breaking his industry’s expectation of silence, actor and activist is speaking with one voice

If you really want to know what shaped John Boyega’s attitude to high-pressure situations – if you want the creation myth that perhaps explains why he reacts the way he does when he is cornered or challenged or merely required to stand up and be counted – then you probably need to know about the time he was stranded at sea in Nigeria. It was eight years ago now, in the soupy, grey-skied heat of the country’s 2012 rainy season. He was 20 years old, fresh from his film debut in Attack The Block and back in his ancestral motherland to appear in the screen adaptation of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel Half Of A Yellow Sun.

He was, in other words, not yet the John Boyega he is now – not the performer coveted by directors as varied as JJ Abrams, Kathryn Bigelow and Steve McQueen – but he was well on his way. And it was around this time that, following a catalogue of filming-related calamities (a protective plug getting accidentally lodged in his ear during an action scene; a frantic dash to find something approximating a specialist doctor to aid its careful removal; a driver depositing him in an unfamiliar dock so he could make his way back to set), Boyega found himself stumbling aboard the wrong commuter vessel.

It was only meant to be a 45-minute journey, scudding slowly out from the port city of Calabar to the production hub in a nearby riverside outpost called Creek Town. But then, suddenly, out on the water, the boatman cut the engine and turned his attention to Boyega. Whether it was something in Boyega’s demeanour or his Western dress, this enterprising captain, in a country where a degree of cheerful extortion is generally a daily fact of life, scented an opportunity to make some cash. So he laid it out simply: if Boyega wanted him to start the engine again, then he needed to hand over some more money. Fast. Here, miles away from a camera or craft services table, the actor found himself involved in the sort of damp-browed, character-defining standoff that is the hallmark of any great thriller.

‘SOMETIMES YOU JUST NEED TO BE MAD. SOMETIMES YOU DON’T HAVE ENOUGH TIME TO PLAY THE GAME’

“I felt very fearful,” says Boyega, remembering the expectant glances of the other passengers, the lapping sound of the water, the tense sway of the becalmed boat. “But I think it was the first time that I went into fight-or-flight mode and was just like, ‘OK, well, both of us are going to die today, then, because I’m definitely not going to back down.’ I told him, ‘I’m going to pay you the money that’s owed, but we’ll both be dying in the sea here if you think I’m going out like this or that you can get more from me.’”

Of course, it did not come to a physical confrontation and two watery graves in the Atlantic (after 15 minutes or so of noisy back-and-forth, Boyega heard the approaching growl of a police boat, manned by AK-47-toting officers sent by the film’s production staff to look for him; history sadly does not record just how quickly the boat’s would-be hostage taker soiled his pants). But the point of this skilfully relayed, typically Boyega-ish story is not really its dramatic resolution. No, it is the conduct of its protagonist. It is the fact that, alongside the other tales he will tell me about a childhood punctuated by incidents of racism and police profiling – about how when he first went to Nigeria as a ten-year-old he witnessed his uncles slaughtering a cow and fought the shiver down his spine to help heft buckets of still-warm blood – it is offered up to better illuminate exactly what this 28-year-old has been through and what he is made of. It is part of the accumulative origin story that, as he faces a Star Wars-free future for the first time in six years and takes a lead role in the BBC’s forthcoming Windrush generation saga Small Axe, is animating his choices both on screen and off it.

And it is, ultimately, one way to obliquely explain exactly what happened at the Black Lives Matter protest in London on 3 June, when Boyega was handed a megaphone with little warning and ended up indelibly writing his name into the history of the racial justice movement that will come to define this year just as much as Covid-19 and interminable Zoom quizzes.

The plan on that overcast, emotionally charged day in London, he notes with a wry smile, had been for him to “protest quietly”. Energised but not fully sated by the online debate that had followed George Floyd’s death, he and his older sister, Grace, pulled on their masks, hopped in an Uber and spent three hours mingling anonymously with the thousands of protesters flowing towards Hyde Park. Then, after they had arrived, Boyega reconnected with the BLM organisers he had been in touch with on Instagram earlier that week. Would he be willing, the organisers wondered, to climb up an improvised stepladder dais and say a few words to the crowd while they waited for the next scheduled speaker?

‘WHAT I SAY TO DISNEY IS DO NOT MARKET A BLACK CHARACTER AS IMPORTANT AND THEN PUSH THEM ASIDE’

Though widely shared now (one Twitter clip has been viewed 3.6 million times), what happened next still has the power to quicken the pulse. For almost five minutes, Boyega – sounding every inch the literal son of a preacher – rallies the crowd with a visceral, personal and profane account of what it’s like to be black in the same societies that gave us the barbaric deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Stephen Lawrence and the countless others like them. “I need you guys to understand how painful this shit is,” he tells the mass of raised fists and camera phones, his voice cracking. “I need you to understand how painful it is to be reminded every day that your race means nothing! That isn’t the case any more. That is never the case any more.” Voices whoop and spur him on. “We are a physical representation of our support for George Floyd. We are a physical representation of our support for Sandra Bland… for Stephen Lawrence, for Mark Duggan!”

He is angry, of course, screaming himself as hoarse as a pro-wrestling heel and letting emotion spring from him like a burst pipe. But he is almost transgressively vulnerable too, open and tearful and scared in a way that black men – and incredibly famous black men, at that – are rarely seen publicly.

For Steve McQueen, the Oscar-winning director who cast Boyega in Small Axe, this was the most striking aspect of his speech. “I think of myself as a warrior, because I’m all about battles, but all of a sudden [it was like] he had just taken off his armour and said, ‘Here it is,’” he tells me, over the phone. “It was kind of frightening in a way. You’re thinking, ‘Get your sword up.’ But there’s strength in vulnerability and being naked. He shone very brightly and I rang him a few days after to say thank you.”

Boyega himself stresses there was nothing planned or calculated about the speech, its sentiment and delivery was something he had been building towards. “I feel like, especially as celebrities, we have to talk through this filter of professionalism and emotional intelligence,” he says. “Sometimes you just need to be mad. You need to lay down what it is that’s on your mind. Sometimes you don’t have enough time to play the game.” The rawness, he says, came from looking out into the crowd that day and seeing his own fear and weariness mirrored in the eyes of the other black men present. “That just made me cry,” he adds. “Because you don’t get to see that.”

Well, now, enough is enough. After almost a decade in the business, after the life-changing, overwhelming and at times stifling reality of operating within the sprawling Death Star of franchise filmmaking, he is just about done abiding by any old rules. As a certain Nigerian boat captain can grimly attest, John Boyega is not really the man that you think he is. And now he is finally ready to let the world know.

For Boyega, 2017 was a year thick with opportunity. If capturing the role of Finn in 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens represented the professional equivalent of an enormous poker win, then this was the period when he effectively staggered to the cashier window with an armful of chips. Having already wrapped Rian Johnson’s sequel, The Last Jedi, he also made Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, founded his own company, Upper Room, in order to produce and star in Pacific Rim: Uprising, and, by spring, he was headlining a revival of bruising German tragedy Woyzeck at The Old Vic in London.

This era looked, from the outside, like a career apex; the sort of deft mix of enviable professional projects assembled specifically to torment other young British actors. And so it is a surprise to learn that Boyega looks back on it the way an addict may look back on the days that preceded their arrival at an ocean-side rehab facility.

‘ALL OF A SUDDEN HE HAD TAKEN OFF HIS ARMOUR AND SAID, “HERE IT IS.” HE SHONE VERY BRIGHTLY’ – STEVE MCQUEEN

“That was a weird time, man,” he says, with a sigh. “I took on too much work, basically. There was a lot going on; a lot of noise and a negative vibe. I just overshot it and really took the mickey out of myself by not having enough of a break [between projects].” He tried to pour his anger and frustration into his work – telling himself, as he carried out a violent murder at the end of each performance of Woyzeck, that he was actually strangling all the things he suddenly couldn’t control in his life. But he felt strung out and spread too thin. He felt that the tyranny of his schedule – the longed-for career opportunities that he had deemed too good to turn down – were disrupting “family time, dating time, all of that”. He felt, really, that the harried reality of being an in-demand actor wasn’t all that much fun. “At the time I just wanted someone to punish,” he says. “But there was no one but me.” And there was something else too: a gnawing doubt about the intergalactic blockbuster that everyone kept telling him he was so fortunate to be involved with.

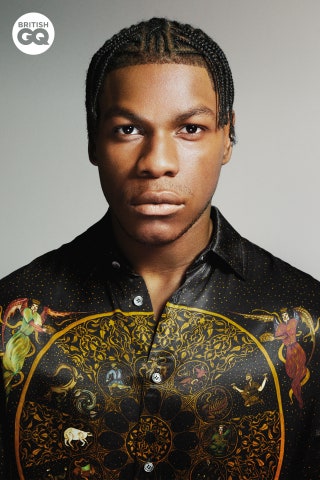

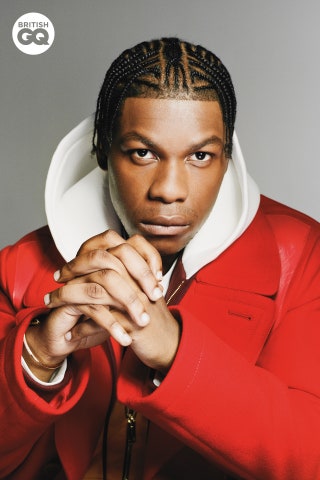

So what changed? Well, there were a number of things, which we’ll come to, that coalesced to provide some answers. But it is at this stage that I should pause to point out that, here and now, it is hard to square this period of personal crisis with the contented, self-actualised man sitting opposite me. We meet on a late July day, in the privately booked upstairs of a lightly boujie restaurant, owned by one of Boyega’s friends, in London’s St John’s Wood just as the city edges towards another post-lockdown heatwave. There is an introductory elbow bump as two alcohol-free Mojitos are ordered (he is a long-term teetotaller; it seemed polite to join him) and time to take in a physical transformation that, in its own way, is as dramatic as the philosophical shift he has clearly undergone in recent years. Mostly gone is the puppyish, kinetic figure that many first met during the extended press jamboree of The Force Awakens. Though he will occasionally oblige with a pitch-perfect impression (Boris Johnson garbling evasively at a press conference, say), his resting expression is a determined, all-business smoulder; he now possesses stillness and the gym-thickened build of a Depression-era heavyweight; and there is a high decibel, pulpit-ready passion and ferocity to the way his sentences unfurl and crescendo with unblinking eye contact. His hair too – grown out for the past two years and worn today, as it is in his GQ cover shoot, in tightly plaited, swishing braids – is, it turns out, of almost Samsonian significance to him.

“When black men grow out their hair it’s a very powerful thing,” he says. “Culturally, it stands for something.” In fact, it was what Boyega saw as attempts to control his appearance – allied with the smothering feeling of his packed diary leading into 2017 – that caused him to question his place in the sausage machine of big-ticket moviemaking, that made him wonder if there was actually room for someone who looked like him to exist on his own terms in an industry generally built to white standards and white norms.

In the continued afterglow of that first, franchise-defibrillating Star Warsfilm, he continued to notice a stylist he’d hired when he first started doing press “cringing at certain clothes I wanted to go for”, the hairdresser who had no experience of working with hair like his but “still had the guts to pretend”, and he decided that he could no longer grin and bear it like a grateful competition winner. “During the press of [The Force Awakens] I went along with it,” he notes. “And obviously at the time I was very genuinely happy to be a part of it. But my dad always tells me one thing: ‘Don’t overpay with respect.’ You can pay respect, but sometimes you’ll be overpaying and selling yourself short.”

With the Lucasfilm-branded elephant in the room acknowledged, it is even harder to ignore. This is Boyega’s first substantial interview since finishing the franchise – his first since last year’s The Rise Of Skywalker tied a highly contentious, hurried ribbon on the 43-year-old space saga. How does he reflect on his involvement and the way the newest trilogy was concluded?

‘I TOOK ON TOO MUCH WORK [IN 2017]. I WANTED SOMEONE TO PUNISH, BUT THERE WAS NO ONE BUT ME’

“It’s so difficult to manoeuvre,” he says, exhaling deeply, visibly calibrating the level of professional diplomacy to display. “You get yourself involved in projects and you’re not necessarily going to like everything. [But] what I would say to Disney is do not bring out a black character, market them to be much more important in the franchise than they are and then have them pushed to the side. It’s not good. I’ll say it straight up.” He is talking about himself here – about the character of Finn, the former Stormtrooper who wielded a lightsaber in the first film before being somewhat nudged to the periphery. But he is also talking about other people of colour in the cast – Naomi Ackie and Kelly Marie Tran and even Oscar Isaac (“a brother from Guatemala”) – who he feels suffered the same treatment; he is acknowledging that some people will say he’s “crazy” or “making it up”, but the reordered character hierarchy of The Last Jedi was particularly hard to take.

“Like, you guys knew what to do with Daisy Ridley, you knew what to do with Adam Driver,” he says. “You knew what to do with these other people, but when it came to Kelly Marie Tran, when it came to John Boyega, you know fuck all. So what do you want me to say? What they want you to say is, ‘I enjoyed being a part of it. It was a great experience…’ Nah, nah, nah. I’ll take that deal when it’s a great experience. They gave all the nuance to Adam Driver, all the nuance to Daisy Ridley. Let’s be honest. Daisy knows this. Adam knows this. Everybody knows. I’m not exposing anything.”

He is on a breathless roll now, breaking his long corporate omerta to touch on the unthinking, systemic mistreatment of black characters in blockbusters (“They’re always scared. They’re always fricking sweating”) and what he sees as the relative salvage job that returnee director JJ Abrams performed on The Rise Of Skywalker (“Everybody needs to leave my boy alone. He wasn’t even supposed to come back and try to save your shit”). Even though he also acknowledges that it was an “amazing opportunity” and a “stepping stone” that has precipitated so much good in his life and career, he is palpably exhilarated to be finally saying all this. But to dismiss these words as merely professional bitterness or paranoia is to miss the point. His primary motivation is to show the frustrations and difficulties of trying to operate within what can feel like a permanently rigged system. He is trying, really, to let you know what it feels like to have a boyhood dream ruptured by the toxic realities of the world.

HE NOTICED HIS STYLIST FOR THE STAR WARS PRESS JUNKETS ‘CRINGING AT CERTAIN CLOTHES I WANTED TO GO FOR’

The early life of the boy born John Adedayo Bamidele Adegboyega has been both eagerly raked over and wilfully sensationalised. Born in Camberwell, South London, to Nigerian immigrants, Samson, a Pentecostal minister, and Abigail, a carer, he grew up in Peckham with his two older sisters, Grace and Blessing. Thanks to the fact he went to the same primary school as Damilola Taylor – and was among the last people to see him alive before his murder in 2000 – Boyega’s early interactions with the British press tended to require a kind of active resistance to attempts to neatly frame his story as a case of talent blooming from deprivation and tragedy. There is, in previous interviews, what feels in hindsight like an understandable urge to accentuate the positives of a loving, creative upbringing where his feel for performing soon brought him into the nurturing orbit of a community initiative called Theatre Peckham and, eventually, his mentor and friend Femi Oguns’ Identity School Of Acting.

Today is different. Today, whether because of age or the general openness of the post-Black Lives Matter era, he seems more comfortable digging into the specific challenges and complexities of growing up black on a council estate. He tells me about his first experience of a racist attack while visiting relatives in Thamesmead, when he and his family were pelted with bottles and slurs that he didn’t yet fully understand (“All I was hearing was ‘monkey’ and ‘gorilla’. Before then, my parents had wanted me to see the world in its best light”). He relays the day his father was profiled by the police as he drove (“I remember we were followed home from church and they got us all out of the car”). Oh, and there was the time the Boyega door was punctured with a cutlass following a dispute with some neighbours (“It was an altercation about a dropped piece of biscuit”).

‘YOU GUYS KNEW WHAT TO DO WITH DAISY RIDLEY AND ADAM DRIVER. WHEN IT CAME TO [ME], YOU KNOW F*** ALL’

But there are also multiple belly laugh-inducing tales about Samson and his habit of fearlessly banging down every door in the neighbourhood if his son was ever late coming home. “Whether it was drug dealers or kingpins opening up the doors, he just wouldn’t care,” Boyega says, shaking his head.

This was the multifaceted environment that birthed him. And in 2010, at the age of 18, he was chosen from a pool of more than 1,500 adolescents to appear as gang leader Moses in Joe Cornish’s cult South London-set sci-fi mash-up Attack The Block. “It’s very rare that you find someone, especially at that age, who holds the screen,” is how McQueen describes the uncanny magnetism of that breakthrough performance. “He [was] a bona fide movie star.”

Other directors agreed. And, in 2014, he found himself brought into the Star Wars fold by JJ Abrams. Cue his reveal as a conflicted Stormtrooper once known as FN-2187, an absurd attempted boycott, the fourth highest-grossing film of all time and, laterally, the millions that enabled Boyega to surprise his parents with their own brand-new house three years ago. Yet, again, this is another instance when Boyega seems keen to revise the public record on how something really played out. Whereas previously he responded to the flagrantly racist commentary that greeted his casting in The Force Awakens with bullishness (“Get used to it :)”, as his since-deleted Instagram response post had it), now he is keen to discuss the lasting psychic wounds that an ordeal like that leaves.

‘NOBODY ELSE IN THE STAR WARS CAST HAD PEOPLE SAYING THEY WOULD BOYCOTT THE MOVIE BECAUSE [OF THEM]’

“I’m the only cast member who had their own unique experience of that franchise based on their race,” he says, holding my gaze. “Let’s just leave it like that. It makes you angry with a process like that. It makes you much more militant; it changes you. Because you realise, ‘I got given this opportunity but I’m in an industry that wasn’t even ready for me.’ Nobody else in the cast had people saying they were going to boycott the movie because [they were in it]. Nobody else had the uproar and death threats sent to their Instagram DMs and social media, saying, ‘Black this and black that and you shouldn’t be a Stormtrooper.’ Nobody else had that experience. But yet people are surprised that I’m this way. That’s my frustration.”

He has made peace with a lot of this now (following that intense 2017 period he attended therapy to deal with some “horrible personality traits, [such as] anger”) but he lets his point settle as our mocktails melt to minted slush on the low table between us. And I realise his feelings about the sidelining of people of colour in tent-pole properties – and his words at the Black Lives Matter protest – all flow from this specific pain and frustration. I realise it is another characteristic response to a fight-or-flight moment. And I realise that, in the face of both overt and covert discrimination, loudly and proudly proclaiming your culture might be the sanest thing you can do.

One day, on the set of Small Axe – when Boyega was still sporting the period police uniform and neatly pruned Afro hairpiece of his character, Leroy Logan – a white member of the production staff approached him. He wanted to tell him that, just like the officers they were depicting in this episode, he had been a member of the Met on the beat at a time when racism was even more rampant. He had, in fact, been part of a group of arresting officers who he had seen plant some evidence on a black suspect. And when he told his superiors the truth, he was transferred to another station and labelled a snitch.

‘WHEN BLACK MEN GROW THEIR HAIR OUT IT’S A VERY POWERFUL THING. IT STANDS FOR SOMETHING’

“He was telling me about that experience,” says Boyega, taking up the tale, “and he goes, ‘Every day I’m watching you act, I’m watching Steve McQueen direct and I’m seeing all these individuals from different backgrounds coming together on set. And I’m seeing people properly telling this story that I lived through. So no one can say to me that unity isn’t one of the best things, when it really, truly works.’” This is a moment that serves to illustrate both the special atmosphere on McQueen’s five-part anthology and the important function it will serve as a timely means to excavate crucial parts of Britain’s black immigrant history.

Boyega’s standalone film within the BBC miniseries, Red, White And Blue, sees him depict a black Met policemen, inspired to join the force – and hopefully change it from within – after his Jamaican father is assaulted by two officers. Though set in the 1980s, it could scarcely be more relevant. And you get the sense that Boyega, who recently wrapped his final scenes with some socially distanced filming days post-lockdown, relished the opportunity to make something so earthbound and urgent after an extended period making blockbusters with directors whose life experience differed wildly from his.

“Steve [brought] up things I could relate to and comes with a creative mind like I’ve never experienced before,” he says. “It reminded me of my happiest days at drama school. Being on set was like I’d been given the chance to breathe.” McQueen, for his part, relished the fact that the actor wanted to “be put in uncomfortable situations” and they are already discussing the possibility of working together again. “Right now, he’s dangerous,” says McQueen. “And that’s where I want to be.”

For Boyega, during a personally transformative period, it feels like a closing of the loop. Not just because it speaks, broadly, to his plan to use an upcoming tour of schools to promote careers in film and television to children from underrepresented minorities, but also because the depiction of London in the 1980s has brought him greater understanding of the city his parents moved to, the daily battles they had to fight for acceptance, the start of his own journey and his own desire to start a family (“Just have to find a lady first, man”).

‘BEING ON SET [FOR SMALL AXE] WAS LIKE I HAD BEEN GIVEN THE CHANCE TO BREATHE’

His mother and father are comfortably marooned in rural Nigeria at the moment, so he is also thinking about when he may next see them and reminiscing about his favourite stories. Which brings him to the one about the snatched purse. His parents were in Peckham one day, coming out of their car, when a man sprinted up beside them, grabbed another woman’s bag, knocked her to the floor and started running away.

“And my dad, straight-up Hulk, straight-up Iron Man, straight-up Doctor Strange, got to stepping,” says Boyega, with a broad grin. “He starts running after the guy. Then he stopped and just screamed, ‘Drop it!’ The guy who was running just dropped the bag. My dad walked up, picked it up and gave it to the woman.” He laughs. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘Dad, if she was buff I know you would have dealt her a snog at that moment, if you weren’t married and your wife wasn’t standing there.’”

Perhaps that’s where you’ve inherited it from, I suggest: the fact you can’t stand by and watch or stay silent if you think something isn’t right. The thought, evidently, has not occurred to him. He looks momentarily lost for words, for the only time during our conversation. “Maybe, man,” he says, smiling again, the idea bringing a warm glow of realisation to his face. “Now that you say it. Maybe.”

Small Axe is coming to BBC One and iPlayer this autumn