NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM

Museums grapple with rise in pleas for return of foreign treasures, The Guardian

Revealed: Natural History Museum pressured to return remains to Gibraltar and Chile

The Hoa Hakananai’a statue from Easter Island is among the artefacts displayed in the British Museum asked to be returned.

Photograph: Neil Hall/EPA Mark Wilding Mon 18 Feb 2019 13.02 GMT

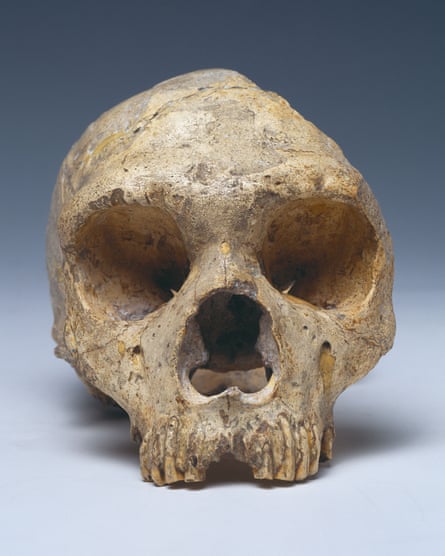

Neanderthal skulls and the remains of an extinct sloth named after Charles Darwin are among the items requested for repatriation from British institutions, as documents reveal museums are facing calls to return some of their most treasured items to their places of origin.

The pressure on museums to grapple with the provenance of their collections has been revealed by freedom of information requests submitted by the Guardian.

A series of high-profile restitution claims have been received by institutions including the British Museum and the Natural History Museum in recent months. They include a call from the government of Gibraltar for the return of Neanderthal remains, including the first adult skull to be discovered by scientists, and a request from Chile for the repatriation of the remains of a now extinct giant ground sloth.

The letters, almost all of which resulted in the requests being rejected, show that long-running restitution claims for high-profile exhibits such as the Parthenon marbles are the tip of the iceberg as debate rages over the right of museums to keep hold of contested collection items.

Last month the Egyptian government called on the National Museum of Scotland to produce certification documents for its Egyptian antiquities after a row broke out over plans to display a casing stone from the Great Pyramid of Giza.

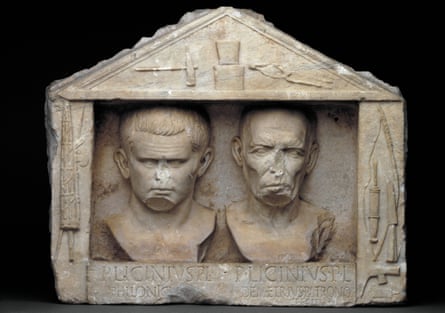

In October last year, the British Museum faced calls to return Hoa Hakananai’a, a basalt statue taken from Easter Island in 1868 and given to the museum by Queen Victoria the following year. In April, the ministry of cultural heritage in Italy requested the return of a marble relief depicting the freedmen Publius Licinius Philonicus and Publius Licinius Demetrius.

A British Museum spokeswoman said discussions about the future of both items were continuing. “We believe the strength of the collection is its breadth and depth, which allows millions of visitors an understanding of the cultures of the world and how they interconnect – whether through trade, conflict, migration, conquest, or peaceful exchange,” she said. “Research into provenance and how objects entered the British Museum’s collection is an active area of work for all of our curatorial departments.”

Marble relief depicting Publius Licinius Philonicus and Publius Licinius Demetrius. Photograph: British Museum

Among the most recent repatriation claims is a request from Gibraltar for two Neanderthal skulls which are on display at the Natural History Museum in London.

The skulls, known as Gibraltar 1 and 2, have played a crucial role in shaping understanding of Neanderthals. Gibraltar 1, an adult female skull, was found in Forbes’ Quarry in 1848 and is believed to be about 50,000 years old. It is described by the museum as a “highlight specimen” in its human evolution gallery. Gibraltar 2 comprises five skull fragments of a Neanderthal child and was discovered at Devil’s Tower in 1926.

In a letter dated 10 September last year, the Gibraltar National Museum wrote to the Natural History Museum director, Sir Michael Dixon, to “formally request the return of the Gibraltar Neanderthal remains” on behalf of the British overseas territory’s government.

“It has been our desire for some time, and we feel that the moment is now the right one, that these human remains should return,” the letter said. “You will agree, I am sure, that it is entirely appropriate for these human remains return [sic] to their place of origin where they will be treated with the care and respect which they deserve.”

Responding to the letter on 20 September, Dixon cited the British Museum Act 1963, which allows for the disposal of collection items only in limited circumstances. “I must therefore decline your request for donation to your museum,” he said.

Dixon wrote that the Neanderthal remains played “a central part in our innovative engagement with the public on human evolution” and were “also in active use for collaborative international research on human origins and variation as part of a large comparative collection”.

Gibraltar 1, a skull from an adult female Neanderthal, is on display at the Natural History Museum. Photograph: Alamy

In August, the museum received a separate request from Chile to return remains of Mylodon darwinii, an extinct ground sloth named after Darwin. That request was also rejected under the terms of the British Museum Act.

A Natural History Museum spokeswoman said: “We are continuing dialogue with both authorities and have confirmed our willingness to meet and discuss any other issues of interest and continue ongoing collaboration in research and public engagement with these countries.”

Prof Clive Finlayson, director of the Gibraltar National Museum, confirmed the organisation was in contact with the Natural History Museum and that possibilities were being discussed.

In March 2017, the V&A received a request from the Welsh Conservative MP Guto Bebb for the return of two “firedogs” taken from Gwydir Castle in Conwy, north Wales. A museum spokeswoman said: “The V&A was gifted these firedogs by a benefactor in 1937. The V&A’s director wrote back to Guto Bebb MP and offered to make the firedogs available as a loan or as a reproduction. To date, this offer has not been taken up by a local museum or the present-day owners of Gwydir Castle.”

The art historian Alice Procter, whose Uncomfortable Art Tours seek to inform visitors about the colonial history of museums, said British institutions would increasingly be forced into “soul-searching” about the provenance of their items – and whether they should be returned.

“This is a really critical time for museums to work out where they stand on these questions,” she said. “Stop hiding behind historical acts. They have little justification for continuing to cite something like the British Museum Act.”

Procter referred to a recent report commissioned by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, which caused a stir in the museum world last November with a call for thousands of African artworks held by French museums to be returned to their countries of origin.

“It’s one of those situations where [museums] are going to have to figure it out or someone is going to figure it out for them,” said Procter.