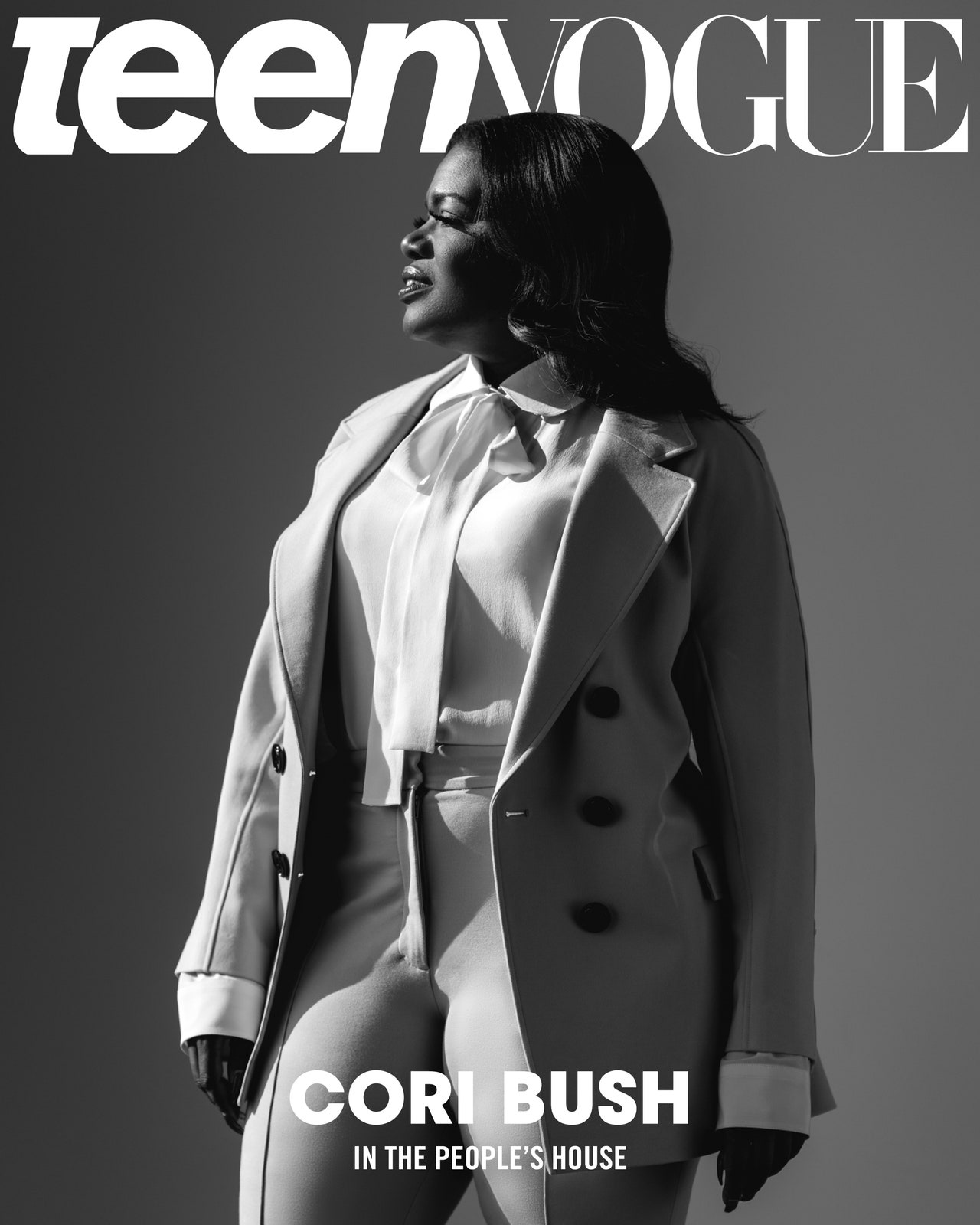

CORI BUSH

On January 3, Cori Bush was sworn in as the first Black woman to represent Missouri in Congress.

Cori was born on 21 July 1976 in St. Louis, Missouri, USA. On August 4, 2020 she defeated William Lacy Clay Junior, the incumbent Democrat U.S. Representative from Missouri’s 1st Congressional District. The following is an interview from TeenVogue published on Tuesday 19 January, 2021. The interviewer is Derecka Purnell.

On January 6, thousands of white election deniers breached the U.S. Capitol building at the encouragement of President Donald Trump. As the mob, which included some police officers and military veterans, swarmed the building, Bush and her new colleagues were ushered away from the House floor, where they had convened to certify Joe Biden’s election as president, to shelter in place.

In her first full week on the job, Bush was already under siege. But she wasted no time.

Her first act as a congresswoman was announcing a resolution to investigate and expel the Republican members of Congress who supported the attempts to overturn the election results.

Since then, she’s been everywhere: coleading the resolution to impeach Trump (again), giving viral interviews about her GOP colleagues’ refusal to follow the same rules as everyone else (“Have they ever had a job before?”), and denouncing the “white supremacist insurrection” at the Capitol.

Bush’s first House floor speech, well, floored the public. “Madam Speaker, St. Louis and I rise in support of the article of impeachment against Donald J. Trump. If we fail to remove a white supremacist president who incited a white supremacist insurrection, it’s communities like Missouri’s First District that suffer the most. The 117th Congress must understand that we have a mandate to legislate in defense of Black lives. The first step in that process is to root out white supremacy, starting with impeaching the white supremacist in chief.” Republicans booed immediately. But Bush is not there for them; she is there to represent the district of the late Maya Angelou, the poet who penned, “Still I Rise.”

“Where did you go to high school?”

When I begin recording my conversation with Cori Bush, this question sits in bold above my notes. The question is charming yet clichéd, but I’m supposed to ask because we are both from St. Louis. Our hometown is so segregated along race and class that based on her answer, I can guess whether she lived in the city or the county; if she woke up at 4:00 a.m. to catch a bus to a school an hour away as part of our court-ordered desegregation program; and most harrowing, her chances of being killed by a lover, neighbor, stranger, or a cop.

“I went to Cardinal Ritter,” Bush says. But I know that already because I cheated and checked her Facebook before I asked.

“Actually, that was the second school,” she continues. “My first semester of freshman year, I went to a predominantly white school. I was told that I was the number one ranked incoming freshman, and tested to that fact.

[They] came to me and said, ‘Oh, you tested number one. We’re going to have you retest because we don’t believe that’s your score. We think that you cheated.’ I think I was still 13 at the time. But I went back into this huge auditorium and retested and ended up scoring even higher.

And so they said, ‘Okay, well we believe you now.’ But the way that I was treated when I entered the school, it was so bad I couldn’t stay. And that’s how I ended up at Cardinal Ritter.”

Cardinal Ritter is a predominantly Black Catholic school in the city of St. Louis. Bush grew up in Northwoods, a tiny, Ferguson-like municipality in St. Louis County. Bush recalls as a child witnessing police racially profile her friends and family, including her father, Errol Bush. He was the mayor of Northwoods in the ‘90s, and made the local paper for allegedly telling the police chief that the force had enough white cops and to hire Black cops who lived in the community. I wonder whether he believed that diversity would help avert the violent police encounters that contributed to his daughter’s prominent rise decades later, including her protests of the police killings of Michael Brown and Anthony Lamar Smith.

During our phone interview, aides interject with questions and Bush rushes around the Capitol preparing to cast votes. She sounds so in awe of her win that, in jest, I ask if she is still campaigning, still trying to convince me of her potential as a politician.

But her vigor and joy come from elsewhere. Bush, a pastor and nurse, shifts her tone to the gospel whisper I recognize from testimony time during church revivals and says, “I don’t want anybody to have to feel hunger the way that I felt hunger. I don’t want anybody else to have to live out of their vehicle with their babies.”

“Well, I won’t even go into all of that,” she continues. “They’ll probably try to take me to jail. But my son was a baby [and] my daughter was a baby when we were living out of a car.

Something happens to you when you feel like you can’t provide for your kids, when you’re cold and there’s nothing, there’s no amount of blankets you can put on yourself to be warm when you’re sleeping in a car. You can’t keep the car running because you’re running down the gas. You can’t keep the lights on [or] people know that you’re in a car.”

I’ve slept in that cold too: the inwarmable bitter of homelessness.

In St. Louis, Black people are almost four times as likely as white people to be unhoused; about 40,000 students in public schools in Missouri experience homelessness during one academic year.

But Bush’s plight didn’t stop there. She was almost killed by an abusive partner, involved in a serious car accident during her first congressional run, and was hospitalized after she likely contracted COVID-19 last year. Bush has overcome nearly impossible odds to secure her seat, which is not merely a story of individual triumph, but one that requires us to examine the social conditions that create those odds in the first place.

Referencing her experiences, including the night that a St. Louis County grand jury declined to bring charges against the police officer who killed Michael Brown, Bush says, “I’m walking in the door as the only person from this movement, with those stripes. I’m walking in the door remembering what it was like when my face was on that cold ground on November 24, 2014, when those police officers were stomping me.”

I confess to her that I have deep reservations about elected officials. The color of a politician is not an indication of what they believe, but it is easier for me to root for representatives Ilhan Omar, Alexandria Ocasco-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, and Ayanna Pressley, four progressive women of color known as “the Squad.” In their individual and collective capacities, they’ve supported a number of policies that depart from establishment Democrats, including defunding the police, championing universal health care, and abolishing Immigrations and Customs Enforcement. But when I see them being friendly with Democrats who are antagonistic toward all of this, I am reminded that the political terrain for progressives is uneven, especially in an electoral system with political action committees, lobbyists, and horrible campaign finance regulations. As a new member of the Squad, how is Bush going to balance being a movement candidate?

“It really bothers me that people will look at me and say, ‘Oh, my gosh, your story is amazing and I really support you and look how far you’ve come. Look at all the adversity you’ve overcome. This is amazing! I love you,’” Bush begins. “And then when they hear somebody say something that they don’t have full information on, then it’s like, ‘Oh, my gosh, she’s being co-opted. Oh yeah, I knew it wasn’t real.’”

She’s right; that is partly my concern.

Black politicians are certainly susceptible to being co-opted. Many wink and nod to progressive phrases without any real commitment to progressive policies. Others make shifts for their personal political gain, like civil rights and black power activists in the 1960s who entered electoral politics.

“People have to look at the reasons why they supported us as a Squad, why we were Squad members before,” the congresswoman says, “and believe in the work that we’re trying to do.”

I ask Bush about her appearance on Representative James Clyburn’s podcast. The elder Black Democrat has been credited with bringing Biden’s presidential bid back to life in the South Carolina primary; Bush campaigned for Senator Bernie Sanders in 2016 and 2020. Clyburn has taken more than $1 million from pharmaceutical political action committees and opposes Medicare-for-all and defunding the police.

“Me and Clyburn, we may not agree on policy, I may not agree with some of the things that he’s done, but I tell you what:

I’m a Black woman. I grew up in the church. I will not dishonor my elders who came through the civil rights movement, which I did not, who endured things that I never did,” Bush explains. “Do I agree with all of it? No. But can we have dialogue? There is something that I can teach him just as much as he can teach me.

The only way you can make change is if you open your mouth and you’re willing to have dialogue and sit with people.”

The election season fervor over Black women has mixed them all together: T-shirts, articles, and memes circulate lists including Harriet Tubman, Fannie Lou Hamer, Shirley Chisholm, and Kamala Harris, celebrating Harris’s historic appointment as the first Black woman vice presidential pick for a major party. Charlotta Bass was actually the first Black woman nominated as VP, who ran on the 1952 Progressive Party ticket and advocated for military budget cuts, universal health care, labor, and civil rights. Tubman was an abolitionist, nurse, healer, and mutual aid organizer. Hamer was a plantation worker and revolutionary freedom fighter who believed in democracy and direct investment in the most economically exploited people. Chisolm was a champion for gender and racial justice causes, and bragged about not being backed by any corporate interests during her presidential run. Harris, a former prosecutor, breaks from these traditions of progressive and radical Black women. She backed Representative William Lacy Clay, an establishment Democrat who held his father’s seat for 20 years, over Bush in the primaries. When I ask Bush about her legislative priorities, they sound much closer to the causes championed by Bass, Tubman, Hamer, and Chisholm.

“What we need to do is put money into mental health. Take money from [police], put it into education, put money into job training programs, to address substance use issues, right? Into our unhoused population. That’s where that money needs to go,” Bush says.

“You give [police] this money, but then we don’t give money to human services. Put it into our health department! Look what happened when COVID hit, again. The areas that are the most marginalized in our communities were the last ones to receive COVID testing and supplies. So that’s what we’re talking about.” She adds, “That also means you don’t need money for tear gas. You don’t need money for noise ammunition, and MRAPs and stockpiling SWAT gear. We’re taking that money back.”

Bush’s interests largely reflect demands from the Movement for Black Lives, Dream Defenders, Democratic Socialists of America, the Sunrise Movement, and other progressive organizations.

She credits social movements for expanding what she thought was possible: “It wasn’t a thing, at least for me, to even think about defunding the police. It never even crossed my mind,” she recalls. Back then, like many of us who did not interrogate the origins, purpose, and function of the law, she was still saying “criminal justice system” and demanding reform for police departments. “Get the cops to act right or get them out, get them off the force,” she says she thought at the time. “But since then, the conversations have continued because the police continue to kill us. All of the organizing that has happened across this country, across the world, actually — the power that we have, it landed us here.”

After the police killing of George Floyd sparked nationwide protests last summer, the demand to defund the police became the most recognizable policy demand emanating from the streets. “So now I’m saying defund the police,” the congresswoman tells me. “Now I know that it’s possible.”

When the raid on the Capitol erupted on January 6, I sent Bush a text, telling her to be safe. I wondered about her two babies who were sleeping in the car with her years ago, and how they were experiencing the events of that day. Now fresh adults at 19 and 20, Bush’s children are no strangers to the violence of daily life in the United States. They have seen everything, she says. “The brutality, losing my home, and so many things. They watched me go through the violent sexual assault that happened after my very first race, when I ran for U.S. Senate. They watched me go through four months where I was not myself, where I couldn’t even cook a meal. I couldn’t step outside of my home. They watched that.”

For years, they also witnessed law enforcement launch authorized attacks on the people of Ferguson, their mom included. “Because I was gone so much during Ferguson, I would ask them before going back out into the streets, ‘Hey, has mama been gone too much? Do you want me to stay home tonight?’” Bush says. “And they would say, ‘No, mom. We know what you’re doing. You out trying to save the world, mama. Go.’”

“And it’s still that way now.”