New Cross Fire: Forty years on from the New Cross fire, what has changed for black Britons?

In 1981, a blaze killed 13 Black teenagers at a London house party in a suspected racist attack. What can be learned from the legacy of the outcry and activism that followed?

Although it happened before I was born, the New Cross fire in 1981 and the National Black People’s Day of Action that followed are landmarks in my identity; growing up in a Caribbean family in the 1980s, they are part of our collective memory. New Cross is fundamental because it contains all the features of racism that Black people in Britain have long suffered: the racial violence, police abuse, neglect by the state; in turn, it tells us of the community’s resistance. Forty years on, recalling the events seems vital, especially in this moment of renewed optimism after the Black Lives Matter protests, because the legacies of New Cross still resonate.

On 18 January 1981, a fire tore through 439 New Cross Road in south-east London, where Yvonne Ruddock was celebrating her 16th birthday with about 60 guests. Wayne Hayes, who was 17 at the time, recalled the carnage in an interview for HuffPost last year. He described how dozens of teenagers and young people, trapped upstairs in the house after the stairs collapsed, resorted to jumping out of second-floor windows, how it was so hot “people’s skin was peeling back” and how in the aftermath he had 140 skin grafts. He shattered 163 bones and has been classed as disabled ever since. Thirteen young people were killed, more than 50 injured and one guest – Anthony Berbeck – died two years later at the age of 20. Many believe he took his own life as a result of the trauma of that night.

Film-maker Menelik Shabazz was 26 at the time and had been living in London since moving as a six-year-old from Barbados. To chronicle both the fire and the community response he made Blood Ah Go Run. “It was a historic moment that was important to document,” he says. The film includes testimony from Armza Ruddock, whose children Yvonne and Paul both died: “Every time I close my eyes I can only see the fire, and the children were screaming, and when they stopped screaming I said, oh God they’re dead.” Shabazz describes his reaction as similar to the experience people felt at Grenfell. “It’s a shock to our system to know that 13 young people ended up dead during a birthday party. People were very angry and upset.” Speaking to him and others it is clear that the anger remains palpable. Shabazz says “it was a racist attack” and it is a widely held assumption in black communities that the fire was started by fascists, most likely using a petrol bomb.

A second inquest in 2004 accepted the fire was started deliberately, but rejected that it was a racist attack. (Coroner Gerald Butler said in his verdict: “While I think it probable … that this fire was begun by deliberate application of a flame to the armchair near to the television … I cannot be sure of this. The result is this, that in the case of each and every one of the deaths, I must return an open verdict.” He said he was satisfied that the fire was not started by a petrol bomb or any other incendiary device, either thrown from outside or inside the house in New Cross Road.) No one has ever been charged in connection with the fire and the case remains unsolved, leading to a complete lack of faith in the official investigations. Collectively, we remember the event as the “New Cross massacre”, where there has been no justice for 14 black young people.

Local history appeared to support the theory that the fire was a racist attack. Ten years before, in 1971, a Caribbean house party had been attacked by firebomb in Sunderland Road, in nearby Forest Hill, leaving 22 injured. And just three years before

in 1978, Deptford’s Albany Empire community theatre was burned down, with the National Front claiming responsibility.

This was the era of far-right extremism, marked by violent racist attacks that Britain prefers to forget. I am old enough to have walked to school and seen chalk directions to NF meetings. But I am young enough to have missed the daily violence and could naively wonder whether the letters stood for “New Flowers”. Chanté Joseph, who is writing a book on British black power, stresses the need to remind people that in recent history “white people in this country made bombs and threw them at us”.

Caribbean house parties were a particular target. In the month after the New Cross fire, rightwing Tory MP Jill Knight raised the issue in parliament, calling for such “noisy” gatherings to be banned on the grounds of public safety, citing race relations legislation as a reason the police’s hands were tied.

There was already a lack of trust among Black communities in the official response and a general perception of the police as racist and discriminatory. Abuse of the so-called “sus laws”, for example, which allowed police to not only stop and search but actually take people into custody on mere suspicion, was a constant issue. Police raids on parties and accusations of brutality were ever present. David Michael, the first black police officer to serve in Lewisham in the 1970s (New Cross is part of the borough), described the force as behaving like an“occupying army”. Unfortunately, this is the approach many felt they took to the investigation of the New Cross fire. The line of inquiry into a firebombing was quickly dropped in favour of a theory that a fight had broken out and that the unruly black youth had caused their own deaths. A number of the survivors were detained for questioning and activists exposed how children were encouraged to sign false statements. The story of Denise Gooding is recounted by Carol Pierre in Black British History: New Perspectives. At just 11 years old, Gooding was subject to hours of questioning into the early morning and pressured to admit there was fighting at the party. Cecil Gutzmore, the academic and activist who was active in the mobilisations after the fire, explained to me that “almost immediately victims became suspects”.

It was not only the police response that fed into community anger.

Such a tragedy should have provoked national mourning but there was silence.

A month later, when 45 people were killed at a Dublin disco, the Queen and the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, immediately sent their condolences. It took Thatcher five weeks to reply to Sybil Phoenix, who had written on behalf of the New Cross families and community, condemning “the failure of… government to reflect the outrage… of the black community”. Thatcher’s disrespect was summed up in her request to Phoenix to pass on her sympathies rather than making any effort to contact the families herself. The lack of an official response to New Cross demonstrated the value placed on black lives in Britain. The media were largely silent or supported the view that the black youngsters had caused the fire themselves. The anger is evident in Gutzmore’s voice as he recalls the silence from those in authority and the New Cross campaigners’ “13 dead, nothing said” slogan.

In 1981, the British Black power movement had been active for at least two decades. Self-help was key, building up education and community support to fill in the gaps left by the neglect of the state. When I interviewed Leila Hassan Howe, who in 1981 was deputy editor of Race Today, for a profile last year in the Guardian Black Lives series, she explained that by the time of New Cross there was “a militancy in the black population and we had to take a stand”. As part of the Race Today Collective, Hassan Howe, along with her future husband, activist Darcus Howe, John La Rose, representing the Black Parents Movement, Roxy Harris and others arranged a community meeting at the local Moonshot club following the fire. She remembers that they were expecting 70-80 people but more than 300 turned up and she “realised that this was a movement of change – something different has happened”. Out of the meeting came the New Cross Massacre Action Campaign (NCMAC). Support was so widespread that £50 of the £19,000 raised for the families came from Black prisoners at Wormwood Scrubs.

Weekly meetings were held and momentum built up for the National Black People’s Day of Action, which was to be an eight-hour event on 2 March 1981. Gutzmore remembers that they were keen not to “rush into the march, we needed to give ourselves time to organise and mobilise properly”. Hassan Howe explained they were eager to make sure it was “not a traditional leftwing demonstration” where they marched, had no impact and then went back to their lives. They chose a Monday to march from New Cross into central London to “disrupt the working day”. Trinidadian intellectual CLR James had an important impact on the Black power movement in Britain and Hassan Howe recalled his advice to not “assume that London is Britain”. Making the day a truly national event was a priority and Darcus Howe toured the country. He was aided by Professor Gus John, one of the foremost Black voices on education in Britain. Overall, more than 70,000 leaflets and 10,000 posters were distributed nationally and John arranged for more than six busloads of protesters from Manchester alone.

The weeks of planning paid off and more than 20,000 almost exclusively black protesters marched across London. For Darcus Howe the day was “Black-organised, Black-led and you felt that”. Gutzmore remains struck by the memory of the march “going under the bridges in south London, the echo of the voices coming back from the crowd”, describing the scene as “really quite extraordinary”. As they marched with chants such as “Black people united will never be defeated”, Hassan Howe recalls that “people just joined in”, swelling their ranks. Some abandoned work for the day and thousands of school-age children took part.

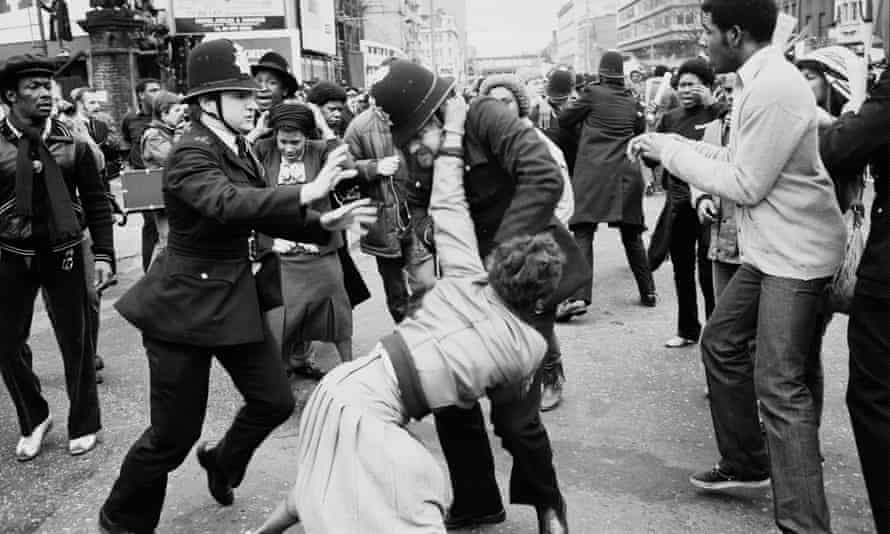

The media were a key target and Gutzmore remembers “marching up Fleet Street, with high-rise buildings on both sides funnelling the sound we were making”. Hassan Howe remembers “a hostile environment” in what was then the home of the newspaper establishment, which included racial abuse and even bananas being hurled at the protesters. The fragile relationship with the press was only further fractured with the coverage of the protest. Throughout the entire day there was one flashpoint with the police at Blackfriars Bridge. Although the route had been agreed, the police erected a cordon as the march approached. Gutzmore remembered thinking that it would go no further but a “whole heap of young men much braver them me were saying ‘onward, forward’ and we just went through their line”. Taking on the police and winning was a key source of pride in the folklore of the march.

The press the following day focused on pictures from Blackfriars Bridge with headlines such as “When the black tide met the thin blue line” (the Daily Mail), the “Day the blacks ran riot in London” (the Sun) and “Rampage of a mob” (Daily Express).

Notwithstanding the press coverage the protest was a major moment in British history. In many ways, it was a culmination of years of organising in Britain, represented by one of the main slogans of the march: “Come what may, we are here to stay”. This was a direct response to the far right’s calls to “keep Britain white” and it became a launchpad for resistance in the 1980s. As one of the protesters insisted in Blood Ah Go Run, “this is the beginning not the end”. Just over a month later Brixton erupted in uprisings against police abuse, which spread across the nation and the decade.

New Cross and the day of action remained in the people’s consciousness for decades. On the 30th anniversary in 2011, Gutzmore was part of efforts by Gus John and Brother Leader Mbandaka for the Afrikan Revivalists Movement to recognise that “we failed to create a national organisation, so let’s have another go”. For several years under the banner of the interim National Afrikan of Peoples Parliament anniversary marches took place to mark the events. I travelled down from Birmingham to speak at the 2014 march and remember how raw the emotion was about the fire and aftermath. Hundreds marched with more joining in spontaneously just like in 1981, venting the same anger and frustration. At the time, it was exhilarating to feel the resistance, but on reflection there is a flipside. Chanté Joseph summed up this unease when she told me:

“Forty years since this huge protest that brought London to a halt, not one thing has changed … it’s tiring thinking about all the work that needs to be done to fix racism in this country.”

She stresses the importance of remembering the day, saying that “these memorials need to be treated with way more respect”. Hassan Howe has commented on how many young people she engages with at university have no knowledge of New Cross and the history of racial violence or activism in Britain. Joseph feels this lack of education of Black Britain’s past is intentional because it allows people to treat racism as a non-essential issue in society. As someone who regularly engages in media debates I can certainly testify to this. Joseph is frustrated that we are still stuck on the question “does racism exist in Britain?”, adding that if this is where we still find ourselves in the debate, “we’re not making it out of the ghetto any time soon”.

As much as the Black Lives Matter summer may seem like a new moment, an opportunity for dramatic change, we have been here before and looking back is essential to moving forward. The National Black People’s Day of Action was the crest of a substantial wave of Black power mobilisation, with ripple effects across the decade that crashed into the rocks of Thatcherism, individualism and the myth of equal opportunities. It is ironic that the very gains the Black power movement created in access to education, employment and society are the same factors that led many of us to look for alternatives to mass grassroots political activism. Put it this way, 40 years ago I would not have been a university professor writing this piece for a national newspaper. That day of action after New Cross was supported by Black university students, who were gaining their first significant foothold on campuses. Joseph warns that “people need to learn to be comfortable with being uncomfortable” and that if we are heeding the lessons from New Cross, then that unease should remain palpable. Token PR gestures, diversity schemes and anti-bias training will not be our salvation.

Gutzmore dismisses the idea that the current moment is a time for optimism. He advises that you “can’t be optimistic, all you can do is organise to the best of your ability in whatever circumstances you find yourself”. Out of the ashes of the New Cross fire, we saw the spirit, determination and organisation of Black communities across Britain. If we take one lesson 40 years on it must be that “Black people united, will never be defeated”.

Kehinde Andrews is professor of black studies at Birmingham City University. His book The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World will be published by Allen Lane on 4 February