THE BELGIAN CONGO (DRC) & KING LEOPOLD II OF BELGIUM

The Belgium king Leopold II turned a huge piece of Africa into his rural estate, enslaved its people, and left a legacy of misery that lasts until today

Maurício Brum

When the European powers got together to split Africa among themselves, in late 1884, a piece of the map was left out of the hands of all countries. In the center of the continent, the region of the Congo wouldn’t be left to the Africans themselves (as it happened with Ethiopia and Liberia, the only regions which would remain independent), nor to the colonialist states.

Instead, the huge area was recognized by the Berlin Conference as private property; it belonged solely and exclusively to King Leopold II of Belgium, and would remain like that until the early 20th century.

The Congo Free State was a corporate state in Central Africa privately owned by King Leopold II of Belgium founded and recognized by the Berlin Conference of 1885. In the 23 years (1885-1908) Leopold II ruled the Congo he massacred at least 10 million Congolese Africans by cutting off their hands and genitals, flogging them to death, starving them into forced labour, holding children ransom and burning villages.

In the following years, the Congo Free State would not become known for this peculiar condition, but for another reason, much darker – the extreme brutality which the local population was treated by Leopold’s henchmen, in something that has been described by some historians as Africa’s “forgotten Holocaust”.

The Heart of Darkness

The Congo was then a region shrouded in mysteries and unrest. Covered by a dense tropical forest, it had been little mapped by the Europeans. In the imagination of the superpowers, it was “the heart of darkness”, a denomination eternalized in the title of the novel by Joseph Conrad set there.

The “darkness”, in that case, was a mixture of the backwardness attributed by the European to the African populations with their own lack of knowledge about the geography of the interior of the continent, an ignorance that had generated tens of incorrect – or simply incomplete – maps in the previous centuries.

Although interactions between Europe and Africa had existed for millennia, contact among civilizations had happened especially with peoples who inhabited the north of the continent (like Ancient Egypt) or in the coastal regions (especially during the black slave trade). It was only in the 19thcentury, when explorers funded by European governments and monarchs began to enter the African jungles and rivers, that these zones of doubt were removed from the local cartography.

One of the most famous explorers of that time was Henry Morton Stanley, a Welsh journalist who dedicated most of his life to unraveling Africa’s secrets. He had already become famous for finding alive, in 1871, British missionary David Livingstone, who had gone missing in the continent six years previously; Stanley had also made expeditions to look for the source of the Nile. He was personally hired by Leopold II to map the Congo river basin, and ensure the king’s control of the region.

Even though the riches of the Congo were not entirely known, no European power doubted that such a vast area in the center of Africa could have something else than an unimaginable economic potential.

The region was disputed by countries like France and Portugal – the former even sent their own explorer, Pierre de Brazza, who settled in the northern bank of the Congo river, and gave his name to the capital of present-day Republic of Congo, Brazzaville. However, in this race to take control of other people’s territory, Leopold II would take the lead.

A country as private property

The Belgian king was one of the main encouragers of the Berlin Conference, which redrew the map of Africa – in his own words, Leopold II did not want to take the risk of missing “ A fine chance to secure for ourselves a slice of this magnificent African cake,” as mentions US historian Adam Hochschild in his book ‘King Leopold’s Ghost’, one of the main works on the Congo exploration.

At its end, in 1885, the conference had blown up the previous order of powers in the interior of Africa, and established artificial borders under control of each superpower – and guaranteed that Congo would remain in the hands of the monarch.

His control was intermediated by the African International Association (AIA), a company founded by Leopold which had been Stanley’s formal employer during his expedition, and now turned into the administrative arm of a whole country – in practice, a huge rural estate belonging to Leopold. AIA would eventually be replaced, and the king’s private colony would become known as Congo Free State.

Ironically, Leopold II had an incomparably bigger power in Africa than in his own country; while in Belgium he was a symbolic figure in a parliamentary monarchy system, in Congo he had absolute powers, just like in the old days.

The ABIR Congo Company (founded as the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company and later known as the Compagnie du Congo Belge) was the company appointed to exploit natural rubber in the Congo Free State. ABIR enjoyed a boom through the late 1890s, by selling a kilogram of rubber in Europe for up to 10 fr which had cost them just 1.35 fr. However, this came at a cost to the human rights of those who couldn’t pay the tax with imprisonment, flogging and other corporal punishment recorded.

In a short period of time, the king focused his economic interests in the export of latex, an abundant product in the region’s forests, using troops of mercenaries to force the local population to cater to his interests. The extraction of ivory and mining also helped to fill Leopold’s coffers.

Imposing productivity quotas so high that they were rarely reached, the Congo Free State little by little acquired such infamy that it eventually was denounced by other colonial powers: the mutilation of the local population as a form of punishment for not fulfilling the quotas – and living conditions so precarious that they provoked a mortality rate comparable to a genocide.

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by death. Meanwhile, the Force Publique (the gendarmerie / military force) were required to provide the hand of their victims as proof when they had shot and killed someone, as it was believed that they would otherwise use the munitions (imported from Europe at considerable cost) for hunting.

As a consequence, the rubber quotas were in part paid off in chopped-off hands. Sometimes the hands were collected by the soldiers of the Force Publique, sometimes by the villages themselves. There were even small wars where villages attacked neighboring villages to gather hands, since their rubber quotas were too unrealistic to fill.

A Catholic priest quotes a man, Tswambe, speaking of the hated state official Léon Fiévez, who ran a district along the river 500 kilometres (300 mi) north of Stanley Pool: All blacks saw this man as the devil of the Equator…From all the bodies killed in the field, you had to cut off the hands. He wanted to see the number of hands cut off by each soldier, who had to bring them in baskets…A village which refused to provide rubber would be completely swept clean.

As a young man, I saw [Fiévez’s] soldier Molili, then guarding the village of Boyeka, take a net, put ten arrested natives in it, attach big stones to the net, and make it tumble into the river…Rubber causes these torments; that’s why we no longer want to hear its name spoken. Soldiers made young men kill or rape their own mothers and sisters.

One junior European officer described a raid to punish a village that had protested about the inordinate and unrealistic size of the rubber quota demanded from it. The European officer in command “ordered us to cut off the heads of the men and hang them on the village palisades… and to hang the women and the children on the palisade in the form of a cross”.

The horror

“The baskets of severed hands, set down at the feet of the European post commanders, became the symbol of the Congo Free State,” describes US author Peter Forbath in ‘The River Congo’, a classic on the region’s exploration. “Collecting hands became an end in itself. Soldiers of the Force Publique (the local “army”, paid by Leopold II) brought the hands to the stations, instead of rubber”.

To make up for the low production, troops began to use hands as currency – chopping them was a way of punishing workers who did not fulfill their quotas, and, at the same time, served to show that soldiers were doing their part in exerting pressure over the local population to ensure the fulfillment of these quotas.

Theoretically, hands should serve as a way of proving that those who did not comply with their work had been killed. And, indeed, it is estimated that up to 15 million people died during Leopold II’s rule, either due to the repression or the terrible living conditions imposed on the local population, with widespread disease and malnourishment.

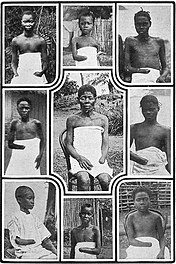

But there were also many survivors: the images of Congolese people with one of their members severed began to circulate throughout Europe, causing immense outrage – even for the standards of colonial exploitation, which was invariably violent, what had been going on under Leopold’s rule was considered beyond the acceptable limits of those who claimed to be in a “civilizing mission”.

The king, however, guaranteed he was not aware of the facts – and claimed to be as shocked as his European critics. From the beginning, he ensured his vision was humanitarian, not economic, and he sought only to civilize Africa’s remote peoples: “opening up the path for civilization in the only part of our world that it still hasn’t reached, piercing the darkness in which entire populations are shrouded, is, I dare say, a crusade worthy of this era of progress,” he stated during the Berlin Conference.

But the dispute of versions became increasingly harder to be won by the Belgian aristocrat – and entered an unsustainable spiral after the execution of a European in the Congo region. Irishman Charles Stokes, a British citizen, was arrested for illegal trade and hung by Belgian authorities without the due legal process in 1895.

The episode placed public opinion and the political and economic power of the United Kingdom against Leopold II.

Different reports and accusations were made, describing in detail what was happening in the Congo, and works of fiction began to include these atrocities in their plots.

Legacy

As an answer to the Stokes affair, British activists and politicians formed the Congo Reform Association (CRA), aiming at denouncing the abuses committed by Leopold II and his henchmen. Several British and American writers, like Joseph Conrad, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Mark Twain, joined the cause, and began to spread through their works the sad reality of the Congo.

The international pressure forced the Belgian government to take action to take the Congo Free State from the hands of their monarch, a transfer that would be concluded in 1908, one year before the death of Leopold II.

The Belgian Congo was then born, now formally a state colony, which would only become independent in the 1960s – now, most of its territory forms the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly Zaire (its neighbor, the Republic of Congo, was formed from the territory of the previous French Congo, around Brazzaville).

The transition was not cheap: despite the accusations, Leopold only relinquished his control after a financial compensation of 215 million Belgian francs, approximately more than 2 billion dollars in present-day currency – the king got rich, but left a legacy of poverty and revolt in Africa.

Nowadays, the GDP of the Democratic Republic of Congo is less than 70 billion dollars per year – less than 800 dollars yearly per capita.

The country occupies the 176th position in the United Nations’ Human Development Index ranking, which lists 189 countries.

Leopold’s Belgium, which inherited the territory and exploited it for more than half a century, is currently in 17th place.