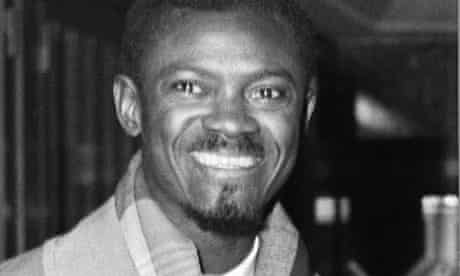

PATRICE LUMUMBA

Summary

Born on 2 July 1925, Patrice Émery Lumumba was a radical anti-colonial leader who became the first prime minister of the newly independent Congo at the age of thirty-five. Seven months into his term, on January 17, 1961, he was assassinated.

Why he was assassinated

Lumumba had become an opponent of Belgian racism after being jailed in 1957 on trumped-up charges by the colonial authorities. Following a twelve-month prison term, he found a job as a beer salesman, during which time he developed his oratory skills and increasingly

embraced the view that Congo’s vast mineral wealth should benefit the Congolese people rather than foreign corporate interests.

Lumumba’s political horizons extended far beyond the Congo. He was soon caught up in the wider wave of African nationalism sweeping the continent. In December 1958, Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah invited Lumumba to attend the anti-colonial All African People’s Conference, which attracted civic associations, unions, and other popular organizations.

Two years later, following mass demands for a democratic election, the Congolese National Movement headed by Lumumba decisively won the Congo’s first parliamentary contest. The left-nationalist leader took office in June 1960.

But Lumumba’s progressive-populist proposals and his opposition to the Katanga secessionist movement (which was led by the white-ruled colonial states of southern Africa and proclaimed its independence from the Congo on July 11, 1960) angered an array of foreign and local interests: the Belgian colonial state, companies extracting the Congo’s mineral resources, and, of course, the leaders of white-ruled southern African states. As tensions grew, the United Nations rejected Lumumba’s request for support. He decided to call for Soviet military assistance to quell the burgeoning Congo Crisis brought about by the Belgian-supported secessionists. That proved to be the last straw.

Lumumba was seized, tortured, and executed in a coup supported by the Belgian authorities, the United States, and the United Nations. With Lumumba’s assassination died a part of the dream of a united, democratic, ethnically pluralist, and pan-Africanist Congo.

The murder of Lumumba and his replacement by the US-backed dictator Mobutu Sese Seko laid the foundation for the decades of internal strife, dictatorship, and economic decline that have marked postcolonial Congo. The destabilization of Congolese society under Mobutu’s brutal rule — lasting from 1965 to 1997 — culminated in a series of devastating conflicts, known as the first and second Congo wars (or “Africa’s world wars”). These conflicts not only fractured Congolese society but also engulfed nearly all of the country’s neighbors, ultimately involving nine African nations and around twenty-five armed groups. By the formal end of the conflict, around 2003, nearly 5.4 million people had died from the fighting and its aftermath, making the war the world’s second deadliest conflict since World War II.

Particularly in light of the Congo’s turbulent trajectory following his assassination, Lumumba remains a source of despair, debate, and inspiration among radical movements and thinkers across Africa and beyond.

The detail from a Congolese perspective

Patrice Lumumba, the first legally elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), was assassinated on 17 January, 1961. This heinous crime was a culmination of two inter-related assassination plots by American and Belgian governments, which used Congolese accomplices and a Belgian execution squad to carry out the deed.

Ludo De Witte, the Belgian author of the best book on this crime, qualifies it as “the most important assassination of the 20th century”. The assassination’s historical importance lies in a multitude of factors, the most pertinent being the global context in which it took place, its impact on Congolese politics since then and Lumumba’s overall legacy as a nationalist leader.

For 126 years, the US and Belgium have played key roles in shaping Congo’s destiny. In April 1884, seven months before the Berlin Congress, the US became the first country in the world to recognise the claims of King Leopold II of the Belgians to the territories of the Congo Basin.

When the atrocities related to brutal economic exploitation in Leopold’s Congo Free State resulted in millions of fatalities, the US joined other world powers to force Belgium to take over the country as a regular colony. And it was during the colonial period that the US acquired a strategic stake in the enormous natural wealth of the Congo, following its use of the uranium from Congolese mines to manufacture the first atomic weapons, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs.

With the outbreak of the cold war, it was inevitable that the US and its western allies would not be prepared to let Africans have effective control over strategic raw materials, lest these fall in the hands of their enemies in the Soviet camp. It is in this regard that Patrice Lumumba’s determination to achieve genuine independence and to have full control over Congo’s resources in order to utilise them to improve the living conditions of our people was perceived as a threat to western interests. To fight him, the US and Belgium used all the tools and resources at their disposal, including the United Nations secretariat, under Dag Hammarskjöld and Ralph Bunche, to buy the support of Lumumba’s Congolese rivals , and hired killers.

In Congo, Lumumba’s assassination is rightly viewed as the country’s original sin. Coming less than seven months after independence (on 30 June, 1960), it was a stumbling block to the ideals of national unity, economic independence and pan-African solidarity that Lumumba had championed, as well as a shattering blow to the hopes of millions of Congolese for freedom and material prosperity.

The assassination took place at a time when the country had fallen under four separate governments: the central government in Kinshasa (then Léopoldville); a rival central government by Lumumba’s followers in Kisangani (then Stanleyville); and the secessionist regimes in the mineral-rich provinces of Katanga and South Kasai. Since Lumumba’s physical elimination had removed what the west saw as the major threat to their interests in the Congo, internationally-led efforts were undertaken to restore the authority of the moderate and pro-western regime in Kinshasa over the entire country. These resulted in ending the Lumumbist regime in Kisangani in August 1961, the secession of South Kasai in September 1962, and the Katanga secession in January 1963.

No sooner did this unification process end than a radical social movement for a “second independence” arose to challenge the neocolonial state and its pro-western leadership. This mass movement of peasants, workers, the urban unemployed, students and lower civil servants found an eager leadership among Lumumba’s lieutenants, most of whom had regrouped to establish a National Liberation Council (CNL) in October 1963 in Brazzaville, across the Congo river from Kinshasa. The strengths and weaknesses of this movement may serve as a way of gauging the overall legacy of Patrice Lumumba for Congo and Africa as a whole.

The most positive aspect of this legacy was manifest in the selfless devotion of Pierre Mulele to radical change for purposes of meeting the deepest aspirations of the Congolese people for democracy and social progress. On the other hand, the CNL leadership, which included Christophe Gbenye and Laurent-Désiré Kabila, was more interested in power and its attendant privileges than in the people’s welfare. This is Lumumbism in words rather than in deeds. As president three decades later, Laurent Kabila did little to move from words to deeds.

More importantly, the greatest legacy that Lumumba left for Congo is the ideal of national unity.

Recently, a Congolese radio station asked me whether the independence of South Sudan should be a matter of concern with respect to national unity in the Congo. I responded that since Patrice Lumumba has died for Congo’s unity, our people will remain utterly steadfast in their defence of our national unity.

The detail from a US perspective

On Sept. 19, 1960, the Central Intelligence Agency’s station chief in Leopoldville, capital of the newly independent Congo, received a message through a top-secret channel from his superiors in Washington. Someone from headquarters calling himself ”Joe from Paris” would be arriving with instructions for an urgent mission. No further details were provided. The station chief was cautioned not to discuss the message with anyone.

”Joe” arrived a week later. He proved to be the C.I.A.’s top scientist, and he came equipped with a kit containing an exotic poison designed to produce a fatal disease indigenous to the area. This lethal substance, he informed the station chief, was meant for Patrice Lumumba, the recently ousted pro-Soviet Prime Minister of the Congo, who had a good chance of returning to power.

The poison, the scientist said, was somehow to be slipped into Lumumba’s food, or perhaps into his toothpaste. Poison was not the only acceptable method; any form of assassination would do, so long as it could not be traced back to the United States Government. Pointing out that assassination was not exactly a common C.I.A. tactic, the station chief asked who had authorized the assignment. The scientist indicated that the order had come from the ”highest authority” – from Dwight D. Eisenhower, President of the United States.

This bizarre plot against the life of Patrice Lumumba led to the imposition of restrictions on the C.I.A. as a result of the investigation conducted by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Activities, under the chairmanship of Senator Frank Church, in 1975. The committee, after extensive closed hearings, revealed in its report that the C.I.A. had plotted to assassinate Lumumba and several other foreign leaders and had engaged in a variety of other illegal activities at home and abroad – all this under four Presidents (two Republicans and two Democrats).

The plot against Lumumba is a classic example of American policy out of control – an assassination attempt launched by the C.I.A. without any known record of a Presidential order, merely on the assumption, which may or may not have been correct, that this was what the President wanted. In July 27, 1960, Washington was host to an unusual visitor. Nowadays, with some 50 independent African states active on the world stage, it is routine for an African Prime Minister to call on an American Secretary of State, but two decades ago the arrival of the leader of a brand-new African republic was a novel and intriguing event – particularly when the Prime Minister was as controversial as this one.

Tall, thin, intense, his eyes flashing behind his spectacles, Patrice Lumumba was a spellbinding orator who had created a nationalist party and had led it to victory in the Congo’s first election. Even before the former Belgian Congo became independent on June 30, 1960, he had figured in the C.I.A.’s reports as a radical who had accepted money from the Belgian Communist Party, appointed a leftist Cabinet and hinted that he might accept Soviet offers of financial aid. But there was no sense of urgency in Washington until two weeks after independence, when Belgian troops moved in to quell a Congolese mutiny against Belgian officers still holding their army posts and Lumumba appealed to the Soviet Union for military assistance against Belgian ”imperialist aggression.”

Both for Lumumba and the United States, it was a decisive encounter. The new Secretary of State, Christian Herter, received him, and spent a frustrating half-hour trying to persuade him to rely exclusively on the United Nations and refrain from calling on outside powers for assistance. His arguments fell on deaf ears. Dillon, who was present at the meeting, testified that Lumumba had struck him and Herter as an ”irrational, almost psychotic personality.” ”The impression that was left,” Dillon said, ”was … very bad, that this was an individual whom it was impossible to deal with. And the feelings of the Government as a result of this sharpened very considerably at that time.”

On Aug. 1, Eisenhower presided at a National Security Council meeting at the Summer White House in Newport, R.I. The chief topic of discussion was the Congo. The Joint Chiefs were concerned about the possibility of Belgium’s bases in the Congo falling into Soviet hands. The council decided that the United States should be prepared ”at any time to take appropriate military action to prevent or defeat Soviet military intervention in the Congo.”

It was at about this time, according to Dillon, that the possibility of assassinating Lumumba came up. The idea was broached at a Pentagon meeting he attended, along with representatives of the Defense Department, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the C.I.A. As Dillon was to testify, ”a question regarding the possibility of an assassination attempt against Lumumba was briefly raised,” only to be ”turned off by the C.I.A.” The C.I.A. people present seemed reluctant to discuss the subject – not, Dillon believed, for any ”moral” reason but because they either regarded the notion as unfeasible or thought the group was ”too large for such a sensitive discussion.” While this conference, in his opinion, ”could not have served as authorization for an actual assassi-nation effort against Lumumba,” the C.I.A. officials ”could have decided they wanted to develop the capability … just by knowing the concern that everyone had about Lumumba.”

By the middle of August, the American strategy of using the United Nations to prevent Lumumba from turning to the Soviet Union was in trouble. Lumumba had broken relations with the Secretary General, claiming that Hammarskjold had yielded to Western pressure in refusing to suppress the Belgian-backed secession of mineral-rich Katanga Province, and he was threatening to expel the United Nations peacekeeping force. From Leopoldville, the C.I.A. station chief, Lawrence Devlin, summed up the situation in alarming terms:

”Embassy and station believe Congo experiencing classic Communist effort take over government. Many forces at work here: Soviets … Communist party, etc. Although difficult determine major influencing factors to predict outcome struggle for power, decisive period not far off. Whether or not Lumumba actually Commie or just playing Commie game to assist his solidifying power, anti-West forces rapidly increasing power Congo and there may be little time left in which take action avoid another Cuba.”

To counter this threat, Devlin proposed an operation aimed at ”replacing Lumumba with pro-Western group.” Bronson Tweedy, head of the African division of the C.I.A.’s clandestine services, replied that he was seeking State Department approval.

The same day, C.I.A. and State Department officials raised the Congo issue with President Eisenhower at a meeting of the National Security Council. According to the minutes of the meeting, Dillon said it was essential to prevent Lumumba from forcing the United Nations contingent out of the Congo: ”The elimination of the U.N. would be a disaster which, Secretary Dillon stated, we should do everything we could to prevent. If the U.N. were forced out, we might be faced by a situation where the Soviets intervened by invitation of the Congo.” Dillon said Lumumba was serving the Soviet Union’s purposes; Dulles said Lumumba was in Soviet pay.

Eisenhower’s reaction, the minutes made clear, was a forceful one: ”The President said that the possibility the U.N. would be forced out was simply inconceivable. We should keep the U.N. in the Congo even if we had to ask for European troops to do it. We should do so even if such action was used by the Soviets as the basis for starting a fight.”

Among those present at the meeting was a middle-level official, Robert H. Johnson, a member of the National Security Council staff, and in l975 he testified before the Church committee as follows:

”At some time during that discussion, President Eisenhower said something – I can no longer remember his words – that came across to me as an order for the assassination of Lumumba…. There was no discussion; the meeting simply moved on. I remember my sense of that moment quite clearly because the President’s statement came as a great shock to me.”

Johnson added that ”in thinking about the incident more recently” he had ”had some doubts” about the accuracy of his impression; it was possible that what he had heard was an order for ”political action” against Lumumba. Yet on further reflection, he said, he went back to feeling that his initial impression was correct. The minutes of the meeting did not contain any such assassination order, but that did not prove anything one way or the other, in Johnson’s view. Under the procedures then in effect, he explained, a Presidential order of such a nature would either have been omitted from the minutes or ”handled through some kind of euphemism.”

In any case, the next recorded step was a cable sent to Devlin in Leopoldville the following day by Richard Bissell, the C.I.A.’s Deputy Director for Plans. Bissell, who was in charge of covert operations, authorized the station chief to proceed with his scheme for replacing Lumumba with a pro-Western group. Devlin, two days later, reported discouraging news: Anti-Lumumba leaders had approached the President of the Congo, Joseph Kasavubu, with a ”plan to assassinate Lumumba,” but Kasavubu had refused, explaining that he was reluctant to resort to violence and that there was no other leader of ”sufficient stature to replace Lumumba.”

At the same time, the American Ambassador in Leopoldville, Clare Timberlake, reported that about 100 Soviet and Czechoslovak ”technicians” had arrived in the Congo and that more were expected shortly. Lodge reported from New York that United Nations sources were ”worried about arms from ‘certain quarters’ being imported through the (Leopoldville) airport under guise of food consignments.” The American Embassy in Athens reported that the Soviet Government had asked permission for 10 Russian cargo planes carrying food to Leopoldville to overfly Greece or land for refueling. Meanwhile, assured by the prospect of Soviet military aid, Lumumba started to move his troops south, in preparation for an assault on secessionist Katanga.

As these reports arrived in Washington, there was a growing sense of alarm in the top echelons of the State Department and the White House.

Purely political intrigue against Lumumba was not, apparently, what the White House had in mind. It was agreed that ”planning for the Congo would not necessarily rule out ‘consideration’ of any particular kind of activity which might contribute to getting rid of Lumumba.”

In effect, Bissell later testified, the C.I.A. Director was obviously under pressure to produce results. The very next day he sent Devlin a cable stressing the view ”in high quarters here” that Lumumba’s ”removal must be an urgent and prime objective.” He gave Devlin still ”wider authority” to replace Lumumba with a pro-Western group, ”including even more aggressive action if it can remain covert,” and authorized expenditure of up to $100,000 ”to carry out any crash programs on which you do not have the opportunity to consult headquarters.”

The implications of this ”wider authority” were spelled out by Bissell to Tweedy, the chief of his African division. Tweedy described their conversation as follows: ”What Mr. Bissell was saying to me was that there was agreement, policy agreement, in Washington that Lumumba must be removed from the position of control and influence in the Congo … and that among the possibilities of that elimination was indeed assassination.”

It was now that the C.I.A.’s top scientist was brought into play. His name was Sidney Gottlieb, he was Bissell’s Special Assistant for Scientific Matters, and he was asked by his superior to prepare biological materials and have them ready on short notice for possible use in the assassination of an unspecified African leader, ”in case the decision was to go ahead.” According to Gottlieb’s testimony, Bissell told him he ”had direction from the highest authority … for getting into that kind of operation”; Gottlieb assumed he was referring to the President.

The scientist checked with the Army Chemical Corps at Fort Detrick, Md., on substances that would ”either kill the individual or incapacitate him so severely that he would be out of action,” and he chose one that ”was supposed to produce a disease that was … indigenous to that area (of Africa) and that could be fatal.” He also assembled some ”accessory materials,” such as hypodermic needles, rubber gloves and gauze masks. At about that time, he was told that the African leader in question was Lumumba, that it had been decided to go ahead, and that he was to take his deadly package to Leopoldville.

By the time he arrived there in September, the situation in the Congo had changed. Disgusted by Lumumba’s military campaign, which by that time had resulted in the death of more than 1,000 civilians, and alarmed by his use of Soviet planes, trucks, weapons and military advisers, President Kasavubu had dismissed the Prime Minister. When Lumumba persuaded Parliament to reverse the dismissal, the Americans and their allies persuaded a young colonel named Joseph Mobutu, the No. 2 man in the army, to take control. (Mobutu would go on to become President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire, as the Congo was renamed in 1971.) Colonel Mobutu promptly ousted all the politicians and expelled the Soviet and Czechoslovak diplomats, along with the military advisers and their equipment. Yet Devlin in his cables put little stock in the stability of the new regime. He feared that the situation could be reversed at any moment, with Lumumba returning to power and inviting the Russians back in.

”Only solution,” he concluded, ”is to remove him from scene soonest.” Dulles agreed. He told Eisenhower on Sept. 21 that the ”danger of Soviet influence” was still present in the Congo and that Lumumba ”remained a grave danger as long as he was not disposed of.”

Five days later, Gottlieb (”Joe from Paris”) arrived in Leopoldville with his poison kit. Ironically, the C.I.A. took its first concrete step toward the assassination of Lumumba three weeks after he was removed as Prime Minister, 12 days after Mobutu seized power and nine days after the expulsion of the Soviet diplomats and military advisers, whose arrival in Leopoldville had caused the panic in Washington and had set the assassination plot in motion.

When Gottlieb reported to Devlin on his mission, the station chief, according to his later testimony, had an ”emotional reaction of great surprise.” As he put it:

”I didn’t regard Lumumba as the kind of person who was going to bring on World War III. I might have had a somewhat different attitude if I thought that one man could bring on World War III and result in the deaths of millions of people or something, but I didn’t see him in that light. I saw him as a danger to the political position of the United States in Africa, but nothing more than that.”

Devlin also had practical objections to the assassination plot: ”I looked on it as a pretty wild scheme professionally…. I explored it, but I doubt that I ever really expected to carry it out.” Yet, like a good bureaucrat, he seems to have kept these doubts to himself, for he told headquarters that he and Gottlieb were on the ”same wavelength,” and he recommended a number of exploratory steps, such as infiltrating Lumumba’s entourage. If headquarters approved, he would instruct one of his agents to ”take refuge with Big Brother” (Lumumba) and ”brush up details to razor edge.” Headquarters told him to go ahead.

Over the next two months, Devlin sent a steady stream of progress reports to Washington through a top-secret channel set up for the assassination project. But, although he emphasized the need for haste, he apparently still had reservations about the scheme, for he kept stalling about putting it into effect. Finally, on Oct. 5, Gottlieb left Leopoldville, later recalling that he dumped the poison in the Congo River before his departure because it was ”not refrigerated and unstable” and was probably no longer sufficiently ”reliable.”

By mid-October, headquarters was impatient. Devlin thought that sending another man was an ”excellent idea.” As for alternative ways of disposing of Lumumba, he recommended that a ”high-powered foreign-make rifle with telescopic scope and silencer” be sent to him by diplomatic pouch. ”Hunting good here,” he cabled cryptically, ”when lights right.”

The senior case officer selected for the task of getting the assassination project unstuck had his own reservations about the idea. The official, Justin O’Donnell, testified before the Church committee that he was called in by Bissell in mid-October and was asked to proceed to the Congo to ”eliminate Lumumba.” ”I told him that I would absolutely not have any part of killing Lumumba,” he said. However, O’Donnell was willing to go to Leopoldville and try to ”neutralize” Lumumba ”as a political factor.” As he explained in his testimony, ”I wanted . . . to get him out, to trick him out, if I could, and then turn him over … to the legal authorities and let him stand trial.” He had ”no compunction” about handing Lumumba over for trial by a ”jury of his peers,” although he realized there was a ”very, very high probability” that he would be sentenced to death.

O’Donnell arrived in Leopoldville on Nov. 3. But he never had a chance to implement his plan to lure Lumumba out. Lumumba slipped away of his own accord on Nov. 27, after a United Nations vote to seat Kasavubu’s delegation rather than his own. Fearing that he would lose the protection of the United Nations force, Lumumba headed for his own stronghold of Stanleyville, 1,000 miles to the east. He was arrested on the way by Colonel Mobutu’s soldiers and was imprisoned in Thysville, 90 miles from Leopoldville.

On Jan. 13, 1961, the Thysville garrison mutinied, demanding higher pay and threatening to put Lumumba back in power. Devlin sent an alarming cable to Washington: ”Station and embassy believe present government may fall within few days. Result would almost certainly be chaos and return (of Lumumba) to power.” He added: ”Refusal to take drastic steps at this time will lead to defeat of (U.S.) policy in Congo.”

The next day, Devlin was informed that Mobutu was going to transfer Lumumba to a prison in a safer place. Three days later, Lumumba was flown to the province of Katanga, domain of his archenemy, the provincial leader Moise Tshombe. As he stumbled off the plane in the provincial capital of Elisabethville, blindfolded, his hands bound behind his back, he was kicked and beaten by Katangan soldiers, thrown into a jeep and driven off.

For the next few weeks, Lumumba’s whereabouts were a matter of confusion and uncertainty. Two days after he was flown to Katanga, the C.I.A. station in Elisabethville cabled headquarters: ”Thanks for Patrice. If we had known he was coming we would have baked a snake.” On Feb. 13, the Katangan authorities announced that he had escaped; three days later they said he had been captured and killed by Congolese tribesmen. No one believed them.

A United Nations investigation, while failing to establish the exact circumstances of Lumumba’s death, concluded that he had been murdered by Katangan officials and Belgian mercenaries on the night of Jan. 17, immediately after his arrival in Elisabethville, with Tshombe’s personal participation or approval.

The C.I.A. has stated that it had no hand in Lumumba’s murder. But a review of the evidence suggests that over a period of four months American officials at the Embassy and the C.I.A. station in Leopoldville encouraged Lumumba’s Congolese opponents to eliminate him before he turned the tables on them and invited the Russians back to the Congo. These officials were following a policy that had been set the previous summer, when Allen Dulles compared Lumumba to Fidel Castro and President Eisenhower agreed he was a threat to world peace. They were to get rid of Lumumba one way or another. If murder ordered by the United States Government and carried out by a C.I.A.-hired assassin was acceptable, then murder carried out by Lumumba’s Congolese opponents, with the help of Belgian mercenaries, was not going to offend anyone’s sensibilities.

The Church committee found ”reasonable inference” that the plot against Lumumba had been authorized by Eisenhower, though, because of the ambiguity of the evidence, it did not reach a conclusive finding to that effect.

The British involvement

MI6 and the death of Patrice Lumumba

By Gordon Corera Security correspondent, BBC News 2 April 2013

A member of the House of Lords, Lord Lea, has written to the London Review of Books saying that shortly before she died, fellow peer and former MI6 officer Daphne Park told him Britain had been involved in the death of Patrice Lumumba, the elected leader of the Congo, in 1961.When he asked her whether MI6 might have had something to do with it, he recalls her saying: “We did. I organised it.”During long interviews I conducted with her for the BBC and for a book that in part covered MI6 and the crisis in the Congo , she never made a similar direct admission and she has denied that there was a “licence to kill” for the British Secret Service. But piecing together information suggests that while MI6 did not kill the politician directly, it is possible – but hard to prove definitively – that it could have had some kind of indirect role. Daphne Park was the MI6 officer in the Congo at a crucial point in the country’s history. She arrived just before the Congo received independence from Belgium in the middle of 1960.

‘Elimination’

Congo’s first elected prime minister was Patrice Lumumba who was immediately faced with a breakdown of order. There was an army revolt while secessionist groups from the mineral-rich province of Katanga made their move and Belgian paratroopers returned, supposedly to restore security. Lumumba made a fateful step – he turned to the Soviet Union for help. This set off panic in London and Washington, who feared the Soviets would get a foothold in Africa much as they had done in Cuba. In the White House, President Eisenhower held a National Security Council meeting in the summer of 1960 in which at one point he turned to his CIA director and used the word “eliminated” in terms of what he wanted done with Lumumba. The CIA got to work. It came up with a series of plans – including snipers and poisoned toothpaste – to get rid of the Congolese leader. They were not carried out because the CIA man on the ground, Larry Devlin, said he was reluctant to see them through. Murder was also on the mind of some in London. A Foreign Office official called Howard Smith wrote a memo outlining a number of options. “The first is the simple one of removing him from the scene by killing him,” the civil servant (and later head of MI5) wrote of Lumumba, who was ousted from power but still considered a threat. MI6 never had a formal “licence to kill”. However, at various times killing has been put on the agenda – but normally at the behest of politicians rather than the spies. Anthony Eden, prime minister at the time of Suez, had made it clear he wanted Nasser dead and more recently David Owen has said that as Foreign Secretary, he had a conversation with MI6 about killing Idi Amin in Uganda (neither of which came to anything).But in January 1961, Lumumba was dead.Did Britain and America actually kill him? Not directly. He went on the run, was captured and handed over by a new government to a secessionist group whom they knew would kill him. The actual killing was done by fighters from the Congo along with Belgians- and with the almost certain connivance of the Belgian government who hated him even more than the American and the British.

Powerful enemies

The comments attributed to Daphne Park by Lord Lea are subtler than saying that Britain killed Lumumba. Lord Lea claims Baroness Park told him that Britain had “organised” the killing. This is more possible. Among the senior politicians in the Congo who made the decision to hand Lumumba over to those who eventually did kill him were two men with close connections to Western intelligence. One of them was close to Larry Devlin and the CIA but the other was close to Daphne Park. She had actually rescued him from danger by smuggling him to freedom in the back of her small Citroen car when Lumumba’s people had guessed he was in contact with her. Do these contacts and relationships mean MI6 could have been complicit in some way in the death of Lumumba? It is possible that they knew about it and turned a blind eye, allowed it to happen or even actively encouraged it – what we would now call “complicity” – as well as the other possibility of having known nothing. The killing would have almost certainly happened anyway because so many powerful people and countries wanted Lumumba dead. Whitehall sources describe the claims of MI6 involvement as “speculative”. But with Daphne Park dying in March 2010 and the MI6 files resolutely closed, the final answer on Britain’s role may remain elusive.

Similar stories were carried by other media:

The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/apr/02/mi6-patrice-lumumba-assassination

The Times: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/mi6-told-to-reveal-truth-behind-lumumba-death-9tcb73llfll

The Aftermath

Patrice Lumumba’s Daughter: I’m Demanding Belgium Give Back My Father’s Remains by JULIANA LUMUMBA, JacobinMag.com, 01.08.2020

Sixty years after his murder, Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba’s body has never been recovered — but some of his teeth were kept as “trophies” by Belgian police.

In an open letter, his daughter demands that the Belgian state return them to his homeland.

Patrice Lumumba was the first prime minister of Congo (now Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC), which he led to independence from Belgian colonial rule in June 1960.

After a century of terror and exploitation in which the Belgian occupier had murdered millions of his compatriots, Lumumba defiantly stood up for the freedom and dignity of Africans.

Even as the Belgian state formally renounced direct political rule, it doggedly defended the dominance of European mining interests and its ties with other, white-minority-ruled African states. Even in its first weeks, Lumumba’s left-nationalist government faced a massive destabilization campaign, as a Belgian-backed secessionist movement launched an armed revolt in Katanga.

Lumumba would ultimately be assassinated by the secessionists on January 17, 1961, after an “anti-communist” military coup. He had been turned over to the secessionists by Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, a figure backed by both Belgium and the United States, who would rule Congo as a murderous military dictator from 1965 to 1997.

At the time of Lumumba’s murder, it was said that he had disappeared — and his body was never recovered. Yet at least some of his remains do still exist. As Belgian Workers’ Party newspaper Solidaire explains, in 2001, amid a parliamentary inquiry into the Belgian state’s role in the assassination, policeman Gérard Soete — chief inspector in secessionist Katanga — admitted to the press that after the killing he had cut Lumumba’s corpse into pieces, before dissolving it in sulfuric acid.

However, Soete had kept two of Lumumba’s teeth, which he pretended to have thrown away; upon his own death, he passed on this macabre “family heirloom” to his own daughter. In 2016, Ludo De Witte, author of a book on Lumumba’s murder, sued the daughter, who had confirmed in a newspaper interview that she had kept hold of the teeth; the remains were then confiscated and moved to Brussels’s Palace of Justice.

Four years on, Lumumba’s teeth are still in the possession of the Belgian state. On June 30, 2020, on the sixtieth anniversary of Congolese independence, Lumumba’s daughter Juliana wrote an open letter to the king of Belgium demanding that his remains finally be returned to his homeland. Here, we reproduce her letter, which is still awaiting a public response.

Sir,

We ask you to consider that words have little force in such grievous circumstances, powerless as they are to properly bring into relief almost sixty years of pain.To tell your majesty how much our hearts buckle under the weight of unspeakable afflictions, we remind you that since January 17, 1961, we have had no information to determine with any certainty the circumstances of our father’s tragic death, nor what has become of his remains.

If anthropologists say that the concern for burial and the funeral ritual are essential human characteristics, each year the DRC, Africa, and the world pay homage to Patrice Emery Lumumba as an unburied hero. The years pass, and our father remains a dead man without a funeral oration, a corpse without bones.

In our culture like in yours, respect for the human person extends beyond physical death, through the care that is devoted to the bodies of the deceased and the importance attached to funeral ritual, the final farewell. But why, after his terrible murder, have Lumumba’s remains been condemned to remain a soul forever wandering, without a grave to shelter his eternal rest?

In our culture like in yours, what we respect through care for the mortal remains is the human person itself. What we recognize is the value of human civilization itself. So why, year after year, is Patrice Emery Lumumba condemned to remain a dead man without a burial, with the date January 17, 1961 as his only tombstone?

We know you are a man of humanity and generosity. So, we refuse to believe that you can remain impassive faced with this interminable grief, which becomes an unbearable mental burden each time we remember that the remains of Patrice Emery Lumumba serve as trophies for some of your co-citizens, as sepulchral items sequestered by your kingdom’s justice system!

Throughout our mother’s life, fifty-three years of it wearing mourning clothes, she fought to give a final resting place to her tender husband. On December 23, 2014, she herself left us, a woman broken-hearted, not having been able to fulfil her duty as a widow. The height of our sorrow is that we know that our mother is not resting in peace.

For my brothers and I, our responsibility as children — our duty as descendants, now that we have ourselves become mother and fathers — is to pay homage to our father, to our progenitor, by offering him a grave worthy of the precious blood that ties us to him, running through our veins. This blood of his was thrown on the ground like water being thrown out — we don’t know where, by whom, how . . . or when!

Since, our father has been our constant grief. He was stripped from the world of the living to live intimately among us, in each of us, but always in an intangible way. There is not a day that goes by when we do not feel his invisible presence. His memory haunts us like the flight of a bird that passes without leaving the slightest trace. Day and night, he visits us in an unchanging dream. When he does not shine like a shaft of light, he blooms like a majestic flower that, born each morning, dies at noon and disappears before twilight.

If Patrice Emery Lumumba was pronounced dead in Katanga, in our country, his remains are scattered in pieces, we don’t know where — except, that is, because of the shameful declarations of ownership of some of his remains, made in Belgium. We, Lumumba’s children, his family, demand the proper return of the relics of Patrice Emery Lumumba to the land of his forebears, so that we might pay our tribute of filial grief.

The greatness of our much-loved father, the eloquence of his heart, and the courageous quest for truth that made him a unique personality, cannot radiate in our own acts and deeds and shine through our works, so long as his soul does not rest in peace in a place worthy of what he represents.

In our country’s traditions, each passing is a birth, every grave a cradle. Our family cannot follow his illustrious footsteps and receive the precious heritage of his genius, his piety, his valiant and patriotic virtues, unless the much-mourned departed can be placed in his perpetual grave.

We, the children of Patrice Emery Lumumba, do not want to leave this painful task to our children, who never knew their grandfather.

We appeal to you to imagine, in these moments which so break our hearts, the added torments which we are inflicting on ourselves through this request, as we build up our hopes that we might give our father a burial to immortalize his memory.

Sixty years after the unspeakable murder, we believe the time for persecution and punishment of Lumumba’s remains has passed, and the time has come for justice.

We only want to bid him farewell, and keenly seek your aid, sir.

In the name of the great Lumumba family, I appeal to your spirit of justice. I remain convinced, from the bottom of my heart, that this request will have a favorable response.

With deep respect,

In the name of the relatives of Patrice Emery Lumumba,

Juliana Amato Lumumba.

Update: Thursday 10 September 2020

Belgium to hand over remains of Congo’s murdered prime minister

The Brussels Times

Lumumba pictured in Brussels at the Round Table Conference of 1960. Credit: Harry Pot- Anefo/Wikimedia Commons (CC0)

A Belgian court has ruled that the remains of Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba, kept by Belgium after his murder, can be returned to his family.

An examining magistrate ruled on Thursday that Lumumba’s tooth could be given back, ruling in favour of the late statesman’s daughter, who in June called on the Belgian state to return her fathers remains.

In June, 64-year-old Juliana Lumumba wrote a letter to King Philippe asking for her father’s remains to be returned “to the land of his ancesters.”

The ruling on Thursday followed a decision by the federal public prosecutor’s office that Lumumba’s remains could be given back, the Belga news agency reports.

In 2002, accounts of Belgium’s involvement in Lumumba’s murder that emerged in past years led Belgium to issue an official apology for its role in the death of the first prime minister of independent Congo.

Lumumba, whose time at the helm of independent Congo lasted less than three months, was overthrown and given up to Belgian-backed separatists militias, who executed him by a firing squad in 1961.

An account given by a Belgian general on his role in the disposal of Lumumba’s death after his capture and murder and sparked a diplomatic crisis between Belgium and Congo and ultimately led to the former’s official apology.

In a 1999 book by sociologist Ludo Di Witte, Belgian Police Commissioner Gérard Soete detailed how, tasked with disposing of Lumumba’s corpse, he had sawed the man’s body into pieces and dissolved it in sulfuric acid.

Soete, who died in 2000, was also shown in a German documentary revealing that the Belgian officer had wrung two teeth from Lumumba’s jaw and kept them, Le Soir reports.

In 2016, one tooth was seized by authorities as part of an investigation by federal public prosecutors on Lumumba’s death.

The ruling on Thursday will allow Lumumba’s relatives to come collect what remains of the late Congolese leader.

Gabriela Galindo

The Brussels Times

Editor’s note: The depths of inhumanity and depravity displayed here are astounding. The Congolese Prime Minister was deposed, murdered, butchered like an animal and then dissolved in a vat of acid by the Belgians, who then in a final act of sadism, wrenched two teeth out of his body and kept it for their own amusement as souvenirs, with no regard to his wife, his children or his humanity. And it is hardly remarked upon.

More than half a century after his murder, Patrice Lumumba’s family are forced to go to court to even be afforded basic decent humanity towards the remains of their father. This should never have been in question and it should never have had to go to court. The dehumanisation of people of African descent continues without a trace of shame. Words like ‘democracy’, ‘mutual respect’ ‘the rule of law’ and ‘civilisation’ fall from the mouths of European leaders like rain yet they display none of those qualities. And then the family are forced to go to Belgium to collect Patrice’s remains themselves, at their own expense, when he was murdered on their own Congolese soil.

Is this your humanity? is this your ‘developed’ world? Is this the moral high ground from which you beseech other nations to be more like you?

Sources: Madeleine G. Kalb’s ”The Congo Cables: From Eisenhower to Kennedy”, The Guardian, Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, Professor of African and Afro-American studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill