White supremacy feeds on mainstream encouragement. That has to stop

Opinion. Gary Younge, Friday 5 April 2019

Rather than making concessions to bigots, politicians must confront them. It’s the only way to end the violence @garyyounge

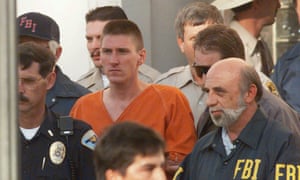

On 19 April 1995, Timothy McVeigh blew up the Alfred P Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people and injuring another 684, in the deadliest act of domestic US terrorism to date. A white supremacist, among other things, he was radicalised by what he regarded as excessive federal government power, US foreign policy and a constellation of bigotries and inadequacies too numerous to mention. He was sentenced to death and placed in a maximum-security prison in Colorado.

While he was there, McVeigh became good friends with Ramzi Ahmed Yousef, who was in the next-door cell. Yousef, who trained in al-Qaida camps in Afghanistan, had tried to blow up the World Trade Center in 1993. Born within four days of each other, here were two young men both unrepentant about their crimes and ideologies, even if McVeigh had ultimately been more successful in inflicting carnage and misery. He was executed in June 2001. Yousef would later state: “I have never [known] anyone in my life who has so similar a personality to my own as his.”

It is presumably in recognition of the unity of purpose between terrorists who attach themselves to Islam and those who embrace white supremacy that the neo-Nazi terror group National Action has called for a “white jihad”. Inadequate young men brimming with rage and brooding resentment, in pursuit of moral certainty, doctrinal purity and a desire to make their mark on a world in which they feel increasingly superfluous and disoriented. They are as made for each other as Yousef and McVeigh.

The central difference is in how these two complementary strands of political violence are understood and challenged. In British news alone this week we have seen a National Action activist in court who planned to kill an MP and a policewoman with a machete; British soldiers in Afghanistan using the Labour leader’s picture for target practice; and a senior Tory and Brexit proponent, Jacob Rees-Mogg, retweeting a key figure from a far-right party in Europe.

White supremacy poses a serious and urgent threat to our political stability, social cohesion and general security. White people are being radicalised at an alarming rate and in disconcerting numbers. The number of far-right terrorists in British prisons tripled between 2017 and 2018.

While the violence may come from the fringes, the encouragement comes from the centre. Only last week, Britain’s counter-terrorism chief, Neil Basu, claimed far-right terrorists were being radicalised by mainstream newspaper coverage; only this week a cartoonist who portrayed refugees as verminreceived a fellowship from the society of editors for his 50 years’ service to the industry. A senior politician has described women in niqabs as looking like letterboxes; and Ukip, polling at 7%, appointed a notorious far-right activist, Tommy Robinson, as an adviser.

There is of course a relationship between the brutal manifestations of bigotry and intolerance and the antiseptic talk of amendments and parliamentary procedure taking place around this stage of the Brexit negotiations. But it is contextual rather than causal. Brexit didn’t create racism. It has exploited, leveraged, amplified, focused, suckled, fed and nurtured it. It has given many licence to say and do things that would previously be regarded as unacceptable. It has laid bare what was hidden and mainstreamed what was marginal.

There were lots of reasons why people voted to leave the European Union, some of which were perfectly reasonable. But it would be more accurate to state that racism – particularly expressed in the form of nostalgia and xenophobia – helped to make Brexit possible, rather than the other way around.

Moreover, this intensification of rightwing nationalism is global. It’s just a few weeks since the deadly shootings in the mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, and a few months since the massacre at the synagogue in Pittsburgh. We live in a period when the presence of fascists in government in Europe is no longer noteworthy and neo-Nazi demonstrators have an advocate in the White House.

White supremacy, and the violence that it spawns, can no longer be lampooned as a postgraduate talking point. It is unpicking the now very fragile fabric that’s keeping us all together.

The number of rightwing extremists arrested in Europe nearly doubled between 2016 and 2017; there was a 74% increase in antisemitic offences in France last year; and the number of hate groups in the US is the highest ever. According to a 2017 Washington Post/ABC poll roughly one in 10 Americans believes that holding Nazi views is acceptable – assuming very few of those were black or Latino, that’s a lot of white people in a very dark place.

Were we to borrow the language directed against Muslims at this point, we would be talking about a “death cult” deep in the Caucasian psyche and calling on moderate, law-abiding members of the white community to step up and speak out. There would be lofty lectures on the Enlightenment and liberal democracy and integration. We would be talking travel bans, rendition and muscular liberalism. The Home Office would revoke Boris Johnson’s citizenship on the basis that he was born in the US and his presence here is not conducive to the public good.

The home secretary might treat a roomful of white people, as John Reid did Muslims in east London in 2006, to tips on parenting. “Look for the tell-tale signs now, and talk to them before their hatred grows and you risk losing them for ever.”

But we won’t borrow that language, not only because it is patronising and racist, holding one group of people collectively responsible for the actions of just a few on the basis of their shared identity. We won’t borrow it because we know it doesn’t work.

While police protection for MPs and more vigilance of hard-right groups might help in the short term, the reality is that the state can only contain a terror threat – it can’t eliminate it. As Northern Ireland showed us, political violence demands political solutions. At some stage that will require our political class to stop pandering to bigotry and start challenging it.

It should be clear by now, if it was not before, that any concession that is made to bigots does not satisfy but emboldens them. That is, in no small part, how we got here. They need to call it out both in the chamber and on the doorstep. If it came from any other group they would have done it already. In the current climate they can no longer avoid it. Their lives may depend on it.

They know that racism is the problem. They have yet to understand that anti-racism is the solution.

• Gary Younge is a Guardian columnist